(Press-News.org) Countless studies demonstrate the virtues of complete smoking cessation, including a lowered risk of disease, increased life expectancy, and an improved quality of life. But health professionals acknowledge that quitting altogether can be a long and difficult road, and only a small percentage succeed.

Every day, doctors are confronted with patients who either cannot or will not quit, says Vicki Myers, a researcher at Tel Aviv University's Sackler Faculty of Medicine. To address this reality, Myers and her fellow researchers, Dr. Yariv Gerber and Prof. Uri Goldbourt of TAU's School of Public Health, examined survival and life expectancy rates of smokers who reduced their cigarette consumption instead of quitting entirely. Their data covered an unusually long period of over 40 years.

While quitters were found to have the biggest improvement in mortality rates — a 22 percent reduced risk of an early death, compared to smokers who maintained their smoking intensity — reducers also saw significant benefits, with a 15 percent reduced risk. These results show that smoking less is a valid risk reduction strategy, Myers says, adding that formerly heavy smokers had the most to gain from smoking reduction.

This research has been published in the American Journal of Epidemiology.

Cutting down for a longer life

To examine the impact of changes in smoking intensity over time, the researchers drew on a sub-cohort of the Israeli Ischemic Heart Disease Study, comprising a database of 4,633 Israeli working males, all smokers at baseline, with a median age of 51 at recruitment. Interviews regarding their smoking habits took place in 1963 and again in 1965, and participants' mortality status was followed for a period of up to 40 years.

During their first interview, participants were placed in categories by daily cigarette consumption — no cigarettes, 1-10 cigarettes, 11-20 cigarettes, and more than 21. In the second interview, researchers noted whether an individual had increased, maintained, reduced, or ceased smoking during the intervening two years, with "increasing" or "reducing" defined as moving up or down at least one category of cigarette consumption within this range.

Unsurprisingly, quitters were the best-off in the long term, with a 22 percent reduction in overall mortality. Those who reduced their smoking by one category or more were seen to have a 15 percent decrease in overall mortality risk and a 23% reduced risk of cardiovascular mortality. In addition, the researchers measured the participants' survival to the age of 80. Quitters saw a 33 percent increased chance of survival to 80 years of age, and reducers a 22 percent increased chance.

Myers says that their study, one of the few to take smoking reduction into account, shows that reduction is certainly better than doing nothing at all. She credits the long-term follow-up period for demonstrating the effect of smoking reduction where other studies have not, because damage done by smoking, and subsequently the recovery process, has a long timeline.

Never too late

One of the important lessons of their study, says Myers, is that it is never too late to tackle your smoking habit. Participants of this study, who were on average fifty years old when the study began, were still able to quit or reduce their smoking, and see long-term benefits from their efforts. Though reduction is a controversial policy — some health professionals believe it dilutes the message of cessation — smokers should take any steps possible to improve their long term health, she counsels.

###American Friends of Tel Aviv University (www.aftau.org) supports Israel's leading, most comprehensive and most sought-after center of higher learning. Independently ranked 94th among the world's top universities for the impact of its research, TAU's innovations and discoveries are cited more often by the global scientific community than all but 10 other universities.

Internationally recognized for the scope and groundbreaking nature of its research and scholarship, Tel Aviv University consistently produces work with profound implications for the future.

Can't stop? Smoking less helps

40-year study shows benefits from reduction, say Tel Aviv University researchers

2012-11-19

ELSE PRESS RELEASES FROM THIS DATE:

Astrophysicists identify a 'super-Jupiter' around a massive star

2012-11-19

TORONTO, ON – Astrophysicists at the University of Toronto and other institutions across the United States, Europe and Asia have discovered a 'super-Jupiter' around the massive star Kappa Andromedae. The object, which could represent the first new observed exoplanet system in almost four years, has a mass at least 13 times that of Jupiter and an orbit somewhat larger than Neptune's.

The host star around which the planet orbits has a mass 2.5 times that of the Sun, making it the highest mass star to ever host a directly observed planet. The star can be seen with the naked ...

School exclusion policies contribute to educational failure, study shows

2012-11-19

AUSTIN, Texas — "Zero- tolerance" policies that rely heavily on suspensions and expulsions hinder teens who have been arrested from completing high school or pursuing a college degree, according to a new study from The University of Texas at Austin.

In Chicago, 25,000 male adolescents are arrested each year. One quarter of these arrests occurred in school, according to the Chicago Police Department. The stigma of a public arrest can haunt an individual for years — ultimately stunting academic achievement and transition into adulthood, says David Kirk, associate professor ...

Call to modernize antiquated climate negotiations

2012-11-19

The structure and processes of United Nations climate negotiations are "antiquated", unfair and obstruct attempts to reach agreements, according to research published today.

The findings come ahead of the 18th UN Climate Change Summit, which starts in Doha on November 26.

The study, led by Dr Heike Schroeder from the University of East Anglia (UEA) and the Tyndall Centre for Climate Change Research, argues that the consensus-based decision making used by the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC) stifles progress and contributes to negotiating ...

A better thought-controlled computer cursor

2012-11-19

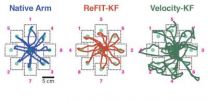

When a paralyzed person imagines moving a limb, cells in the part of the brain that controls movement still activate as if trying to make the immobile limb work again. Despite neurological injury or disease that has severed the pathway between brain and muscle, the region where the signals originate remains intact and functional.

In recent years, neuroscientists and neuroengineers working in prosthetics have begun to develop brain-implantable sensors that can measure signals from individual neurons, and after passing those signals through a mathematical decode algorithm, ...

Fabrication on patterned silicon carbide produces bandgap to advance graphene electronics

2012-11-19

By fabricating graphene structures atop nanometer-scale "steps" etched into silicon carbide, researchers have for the first time created a substantial electronic bandgap in the material suitable for room-temperature electronics. Use of nanoscale topography to control the properties of graphene could facilitate fabrication of transistors and other devices, potentially opening the door for developing all-carbon integrated circuits.

Researchers have measured a bandgap of approximately 0.5 electron-volts in 1.4-nanometer bent sections of graphene nanoribbons. The development ...

Breakthrough nanoparticle halts multiple sclerosis

2012-11-19

New nanoparticle tricks and resets immune system in mice with MS

First MS approach that doesn't suppress immune system

Clinical trial for MS patients shows why nanoparticle is best option

Nanoparticle now being tested in Type 1 diabetes and asthma

CHICAGO --- In a breakthrough for nanotechnology and multiple sclerosis, a biodegradable nanoparticle turns out to be the perfect vehicle to stealthily deliver an antigen that tricks the immune system into stopping its attack on myelin and halt a model of relapsing remitting multiple sclerosis (MS) in mice, according ...

Research breakthrough selectively represses the immune system

2012-11-19

Reporters, please see "For news media only" box at the end of the release for embargoed sound bites of researchers.

In a mouse model of multiple sclerosis (MS), researchers funded by the National Institutes of Health have developed innovative technology to selectively inhibit the part of the immune system responsible for attacking myelin—the insulating material that encases nerve fibers and facilitates electrical communication between brain cells.

Autoimmune disorders occur when T-cells—a type of white blood cell within the immune system—mistake the body's own tissues ...

International team discovers likely basis of birth defect causing premature skull closure in infants

2012-11-19

(SACRAMENTO, Calif.) -- An international team of geneticists, pediatricians, surgeons and epidemiologists from 23 institutions across three continents has identified two areas of the human genome associated with the most common form of non-syndromic craniosynostosis ― premature closure of the bony plates of the skull.

"We have discovered two genetic factors that are strongly associated with the most common form of premature closure of the skull," said Simeon Boyadjiev, professor of pediatrics and genetics, principal investigator for the study and leader of the International ...

Skin cells reveal DNA's genetic mosaic

2012-11-19

The prevailing wisdom has been that every cell in the body contains identical DNA. However, a new study of stem cells derived from the skin has found that genetic variations are widespread in the body's tissues, a finding with profound implications for genetic screening, according to Yale School of Medicine researchers.

Published in the Nov. 18 issue of Nature, the study paves the way for assessing the extent of gene variation, and for better understanding human development and disease.

"We found that humans are made up of a mosaic of cells with different genomes," ...

Optogenetics illuminates pathways of motivation through brain, Stanford study shows

2012-11-19

STANFORD, Calif. — Whether you are an apple tree or an antelope, survival depends on using your energy efficiently. In a difficult or dangerous situation, the key question is whether exerting effort — sending out roots in search of nutrients in a drought or running at top speed from a predator — will be worth the energy.

In a paper to be published online Nov. 18 in Nature, Karl Deisseroth, MD, PhD, a professor of bioengineering and of psychiatry and behavioral sciences at Stanford University, and postdoctoral scholar Melissa Warden, PhD, describe how they have isolated ...

LAST 30 PRESS RELEASES:

The long standing commercialization challenge of lithium batteries, often called the dream battery, has been solved.

New method to remove toxic PFAS chemicals from water

The nanozymes hypothesis of the origin of life (on Earth) proposed

Microalgae-derived biochar enables fast, low-cost detection of hydrogen peroxide

Researchers highlight promise of biochar composites for sustainable 3D printing

Machine learning helps design low-cost biochar to fight phosphorus pollution in lakes

Urine tests confirm alcohol consumption in wild African chimpanzees

Barshop Institute to receive up to $38 million from ARPA-H, anchoring UT San Antonio as a national leader in aging and healthy longevity science

Anion-cation synergistic additives solve the "performance triangle" problem in zinc-iodine batteries

Ancient diets reveal surprising survival strategies in prehistoric Poland

Pre-pregnancy parental overweight/obesity linked to next generation’s heightened fatty liver disease risk

Obstructive sleep apnoea may cost UK + US economies billions in lost productivity

Guidelines set new playbook for pediatric clinical trial reporting

Adolescent cannabis use may follow the same pattern as alcohol use

Lifespan-extending treatments increase variation in age at time of death

From ancient myths to ‘Indo-manga’: Artists in the Global South are reframing the comic

Putting some ‘muscle’ into material design

House fires release harmful compounds into the air

Novel structural insights into Phytophthora effectors challenge long-held assumptions in plant pathology

Q&A: Researchers discuss potential solutions for the feedback loop affecting scientific publishing

A new ecological model highlights how fluctuating environments push microbes to work together

Chapman University researcher warns of structural risks at Grand Renaissance Dam putting property and lives in danger

Courtship is complicated, even in fruit flies

Columbia announces ARPA-H contract to advance science of healthy aging

New NYUAD study reveals hidden stress facing coral reef fish in the Arabian Gulf

36 months later: Distance learning in the wake of COVID-19

Blaming beavers for flood damage is bad policy and bad science, Concordia research shows

The new ‘forever’ contaminant? SFU study raises alarm on marine fiberglass pollution

Shorter early-life telomere length as a predictor of survival

Why do female caribou have antlers?

[Press-News.org] Can't stop? Smoking less helps40-year study shows benefits from reduction, say Tel Aviv University researchers