(Press-News.org) CAMBRIDGE, MA -- Each winter, wide swaths of the Arctic Ocean freeze to form sheets of sea ice that spread over millions of square miles. This ice acts as a massive sun visor for the Earth, reflecting solar radiation and shielding the planet from excessive warming.

The Arctic ice cover reaches its peak each year in mid-March, before shrinking with warmer spring temperatures. But over the last three decades, this winter ice cap has shrunk: Its annual maximum reached record lows, according to satellite observations, in 2007 and again in 2011.

Understanding the processes that drive sea-ice formation and advancement can help scientists predict the future extent of Arctic ice coverage — an essential factor in detecting climate fluctuations and change. But existing models vary in their predictions for how sea ice will evolve.

Now researchers at MIT have developed a new method for optimally combining models and observations to accurately simulate the seasonal extent of Arctic sea ice and the ocean circulation beneath. The team applied its synthesis method to produce a simulation of the Labrador Sea, off the southern coast of Greenland, that matched actual satellite and ship-based observations in the area.

Through their model, the researchers identified an interaction between sea ice and ocean currents that is important for determining what's called "sea ice extent" — where, in winter, winds and ocean currents push newly formed ice into warmer waters, growing the ice sheet. Furthermore, springtime ice melt may form a "bath" of fresh seawater more conducive for ice to survive the following winter.

Accounting for this feedback phenomenon is an important piece in the puzzle to precisely predict sea-ice extent, says Patrick Heimbach, a principal research scientist in MIT's Department of Earth, Atmospheric and Planetary Sciences.

"Until a few years ago, people thought we might have a seasonal ice-free Arctic by 2050," Heimbach says. "But recent observations of sustained ice loss make scientists wonder whether this ice-free Arctic might occur much sooner than any models predict … and people want to understand what physical processes are implicated in sea-ice growth and decline."

Heimbach and former MIT graduate student Ian Fenty, now a postdoc at NASA's Jet Propulsion Laboratory, have published the results from their study in the Journal of Physical Oceanography.

An icy forecast

As Arctic temperatures drop each winter, seawater turns to ice — starting as thin, snowflake-like crystals on the ocean surface that gradually accumulate to form larger, pancake-shaped sheets. These ice sheets eventually collide and fuse to create massive ice floes that can span hundreds of miles.

When seawater freezes, it leaches salt, which mixes with deeper waters to create a dense, briny ocean layer. The overlying ice is fresh and light in comparison, with very little salt in its composition. As ice melts in the spring, it creates a freshwater layer on the ocean surface, setting up ideal conditions for sea ice to form the following winter.

Heimbach and Fenty constructed a model to simulate ice cover, thickness and transport in response to atmospheric and ocean circulation. In a novel approach, they developed a method known in computational science and engineering as "optimal state and parameter estimation" to plug in a variety of observations to improve the simulations.

A tight fit

The researchers tested their approach on data originally taken in 1996 and 1997 in the Labrador Sea, an arm of the North Atlantic Ocean that lies between Greenland and Canada. They included satellite observations of ice cover, as well as local readings of wind speed, water and air temperature, and water salinity. The approach produced a tight fit between simulated and observed sea-ice and ocean conditions in the Labrador Sea — a large improvement over existing models.

The optimal synthesis of model and observations revealed not just where ice forms, but also how ocean currents transport ice floes within and between seasons. From its simulations, the team found that, as new ice forms in northern regions of the Arctic, ocean currents push this ice to the south in a process called advection. The ice migrates further south, into unfrozen waters, where it melts, creating a fresh layer of ocean water that eventually insulates more incoming ice from warmer subsurface waters of subtropical Atlantic origin.

Knowing that this model fits with observations suggests to Heimbach that researchers may use the method of model-data synthesis to predict sea-ice growth and transport in the future — a valuable tool for climate scientists, as well as oil and shipping industries.

"The Northwest Passage has for centuries been considered a shortcut shipping route between Asia and North America — if it was navigable," Heimbach says. "But it's very difficult to predict. You can just change the wind pattern a bit and push ice, and suddenly it's closed. So it's a tricky business, and needs to be better understood."

As part of the "Estimating the Circulation and Climate of the Ocean" (ECCO) project, Heimbach and his colleagues are now applying their model to larger regions in the Arctic.

###

This research was supported in part by the National Science Foundation and NASA.

Written by Jennifer Chu, MIT News Office

Ocean currents play a role in predicting extent of Arctic sea ice

Discovery of feedback between sea ice and ocean improves Arctic ice extent forecast

2012-11-21

ELSE PRESS RELEASES FROM THIS DATE:

Daily steps add up for midlife women's health

2012-11-21

CLEVELAND, Ohio (November 21, 2012)—Moving 6,000 or more steps a day—no matter how—adds up to a healthier life for midlife women. That level of physical activity decreases the risk of diabetes and metabolic syndrome (a diabetes precursor and a risk for cardiovascular disease), showed a study published online this month in Menopause, the journal of the North American Menopause Society.

Although other studies have shown the value of structured exercise in lowering health risks such as diabetes, high blood pressure, and heart disease, this study has shown that habitual physical ...

Brainy babies – Research explores infants' skills and abilities

2012-11-21

Infants seem to develop at an astoundingly rapid pace, learning new things and acquiring new skills every day. And research suggests that the abilities that infants demonstrate early on can shape the development of skills later in life, in childhood and beyond.

Read about the latest research on infant development published in the November 2012 issue of Psychological Science, a journal of the Association for Psychological Science.

How Do You Learn to Walk? Thousands of Steps and Dozens of Falls per Day

How do babies learn to walk? In this study, psychological scientist ...

Short DNA strands in the genome may be key to understanding human cognition and diseases

2012-11-21

Short snippets of DNA found in human brain tissue provide new insight into human cognitive function and risk for developing certain neurological diseases, according to researchers from the Departments of Psychiatry and Neuroscience at Mount Sinai School of Medicine. The findings are published in the November 20th issue of PLoS Biology.

There are nearly 40 million positions in the human genome with DNA sequences that are different than those in non-human primates, making the task of learning which are important and which are inconsequential a challenge for scientists. ...

It takes two to tangle: Wistar scientists further unravel telomere biology

2012-11-21

Chromosomes - long, linear DNA molecules – are capped at their ends with special DNA structures called telomeres and an assortment of proteins, which together act as a protective sheath. Telomeres are maintained through the interactions between an enzyme, telomerase, and several accessory proteins. Researchers at The Wistar Institute have defined the structure of one of these critical proteins in yeast.

Understanding how telomeres keep chromosomes – and by extension, genomes – intact is an area of intense scientific focus in the fields of both aging and cancer. In aging, ...

Pathway identified in human lymphoma points way to new blood cancer treatments

2012-11-21

PHILADELPHIA – A pathway called the "Unfolded Protein Response," or UPR, a cell's way of responding to unfolded and misfolded proteins, helps tumor cells escape programmed cell death during the development of lymphoma.

Research, led by Lori Hart, Ph.D., research associate and Constantinos Koumenis, Ph.D., associate professor,and research division director in the Department of Radiation Oncology, both from the Perelman School of Medicine, University of Pennsylvania, and Davide Ruggero, Ph.D., associate professor, Department of Urology, University of California, San Francisco, ...

University of Tennessee study: Unexpected microbes fighting harmful greenhouse gas

2012-11-21

The environment has a more formidable opponent than carbon dioxide. Another greenhouse gas, nitrous oxide, is 300 times more potent and also destroys the ozone layer each time it is released into the atmosphere through agricultural practices, sewage treatment and fossil fuel combustion.

Luckily, nature has a larger army than previously thought combating this greenhouse gas—according to a study by Frank Loeffler, University of Tennessee, Knoxville–Oak Ridge National Laboratory Governor's Chair for Microbiology, and his colleagues.

The findings are published in the ...

Saving water without hurting peach production

2012-11-21

U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA) scientists are helping peach growers make the most of dwindling water supplies in California's San Joaquin Valley.

Agricultural Research Service (ARS) scientist James E. Ayars at the San Joaquin Valley Agricultural Sciences Center in Parlier, Calif., has found a way to reduce the amount of water given post-harvest to early-season peaches so that the reduction has a minimal effect on yield and fruit quality. ARS is USDA's principal intramural scientific research agency, and the research supports the USDA priority of promoting international ...

Better protection for forging dies

2012-11-21

Forging dies must withstand a lot. They must be hard so that their surface does not get too worn out and is able to last through great changes in temperature and handle the impactful blows of the forge. However, the harder a material is, the more brittle it becomes - and forging dies are less able to handle the stress from the impact. For this reason, the manufacturers had to find a compromise between hardness and strength. One of the possibilities is to surround a semi-hard, strong material with a hard layer. The problem is that the layer rests on the softer material and ...

CDC and NIH survey provides first report of state-level COPD prevalence

2012-11-21

The age-adjusted prevalence of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) varies considerably within the United States, from less than 4 percent of the population in Washington and Minnesota to more than 9 percent in Alabama and Kentucky. These state-level rates are among the COPD data available for the first time as part of the newly released 2011 Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System (BRFSS) survey.

"COPD is a tremendous public health burden and a leading cause of death. It is a health condition that needs to be urgently addressed, particularly on a local level," ...

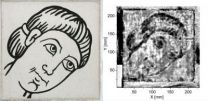

Detective work using terahertz radiation

2012-11-21

It was a special moment for Michael Panzner of the Fraunhofer Institute for Material and Beam Technology IWS in Dresden, Germany and his partners: in the Dresden Hygiene Museum the scientists were examining a wall picture by Gerhard Richter that had been believed lost long ago. Shortly before leaving the German Democratic Republic the artist had left it behind as a journeyman's project. Then, in the 1960s, it was unceremoniously painted over. However, instead of being interested in the picture, Panzer was far more interested in the new detector which was being used for ...

LAST 30 PRESS RELEASES:

When safety starts with a text message

CSIC develops an antibody that protects immune system cells in vitro from a dangerous hospital-acquired bacterium

New study challenges assumptions behind Africa’s Green Revolution efforts and calls for farmer-centered development models

Immune cells link lactation to long-lasting health

Evolution: Ancient mosquitoes developed a taste for early hominins

Pickleball players’ reported use of protective eyewear

Changes in organ donation after circulatory death in the US

Fertility preservation in people with cancer

A universal 'instruction manual' helps immune cells protect our organs

Fifteen-year results from SWOG S0016 trial suggest follicular lymphoma is curable

The breasts of a breastfeeding mother may protect a newborn from the cold – researchers offer a new perspective on breast evolution

More organ donations now come from people who die after their heart stops beating

How stepping into nature affects the brain

Study: Cancer’s clues in the bloodstream reveal the role androgen receptor alterations play in metastatic prostate cancer

FAU Harbor Branch awarded $900,000 for Gulf of America sea-level research

Terminal ileum intubation and biopsy in routine colonoscopy practice

Researchers find important clue to healthy heartbeats

Characteristic genomic and clinicopathologic landscape of DNA polymerase epsilon mutant colorectal adenocarcinomas

Start school later, sleep longer, learn better

Many nations underestimate greenhouse emissions from wastewater systems, but the lapse is fixable

The Lancet: New weight loss pill leads to greater blood sugar control and weight loss for people with diabetes than current oral GLP-1, phase 3 trial finds

Pediatric investigation study highlights two-way association between teen fitness and confidence

Researchers develop cognitive tool kit enabling early Alzheimer's detection in Mandarin Chinese

New book captures hidden toll of immigration enforcement on families

New record: Laser cuts bone deeper than before

Heart attack deaths rose between 2011 and 2022 among adults younger than age 55

Will melting glaciers slow climate change? A prevailing theory is on shaky ground

New treatment may dramatically improve survival for those with deadly brain cancer

Here we grow: chondrocytes’ behavior reveals novel targets for bone growth disorders

Leaping puddles create new rules for water physics

[Press-News.org] Ocean currents play a role in predicting extent of Arctic sea iceDiscovery of feedback between sea ice and ocean improves Arctic ice extent forecast