(Press-News.org) DURHAM, N.C. -- One tropical lizard's tolerance to cold is stiffer than scientists had suspected.

A new study shows that the Puerto Rican lizard Anolis cristatellus has adapted to the cooler winters of Miami. The results also suggest that this lizard may be able to tolerate temperature variations caused by climate change.

"We are not saying that climate change is not a problem for lizards. It is a major problem. However, these findings indicate that the thermal physiology of tropical lizards is more easily altered than previously proposed," said Duke biologist Manuel Leal, co-author of the study, which appears in the Dec. 6 issue of The American Naturalist.

Scientists previously proposed that because lizards were cold-blooded, they wouldn't be able to tolerate or adapt to cooler temperatures.

Humans, however, introduced Puerto Rican native A. cristatellus to Miami around 1975. In Miami, the average temperature is about 10 degrees Celsius cooler in winter than in Puerto Rico. The average summer temperatures are similar.

Leal and his graduate student Alex Gunderson captured A. cristatellus from Miami's Pinecrest area and also from northeastern Puerto Rico. They brought the animals back to their North Carolina lab, slid a thermometer in each lizard's cloaca and chilled the air to a series of cooler temperatures. The scientists then watched how easy it was for the lizards to right themselves after they had been flipped on their backs.

The lizards from Miami flipped themselves over in temperatures that were 3 degrees Celsius cooler than the lizards from Puerto Rico. Animals that flip over at lower temperatures have higher tolerances for cold temperatures, which is likely advantageous when air temperatures drop, Leal said.

"It is very easy for the lizards to flip themselves over when they are not cold or not over-heating. It becomes harder for them to flip over as they get colder, down to the point at which they are unable to do so," he said.

At that point, called the critical temperature minimum, the lizards aren't dead. They've just lost control of their coordination. "It is like a human that is suffering from hypothermia and is beginning to lose his or her balance or is not capable of walking. It is basically the same problem. The body temperature is too cold for muscles to work properly," he said.

Leal explained that a difference of 3 degrees Celsius is "relatively large and when we take into account that it has occurred in approximately 35 generations, it is even more impressive." Most evolutionary change happens on the time scale of a few hundred, thousands or millions of years. Thirty-five years is a time scale that happens during a human lifetime, so we can witness this evolutionary change, he said.

The lizards' cold tolerance also "provides a glimpse of hope for some tropical species," Leal added, cautioning that at present scientists don't know how quickly tolerance to high temperatures -- another important consequence of climate change -- can evolve.

He and Gunderson are now working on the heat-tolerance experiments, along with tests to study whether other lizard species can adjust to colder temperatures.

INFORMATION:Citation:

"Rapid Change in the Thermal Tolerance of a Tropical Lizard." Leal, M. and Gunderson, A. (Dec., 2012). The American Naturalist, 180: 6, 815-822.

DOI: 10.1086/668077

END

HOUSTON - Researchers at The University of Texas MD Anderson Cancer Center have tracked down a cancer-promoting protein's pathway into the cell nucleus and discovered how, once there, it fires up a glucose metabolism pathway on which brain tumors thrive.

They also found a vital spot along the protein's journey that can be attacked with a type of drug not yet deployed against glioblastoma multiforme, the most common and lethal form of brain cancer. Published online by Nature Cell Biology, the paper further illuminates the importance of pyruvate kinase M2 (PKM2) in cancer ...

Areopaguristes tudgei. That's the name of a new species of hermit crab recently discovered on the barrier reef off the coast of Belize by Christopher Tudge, a biology professor at American University in Washington, D.C.

Tudge has been interested in biology his whole life, from boyhood trips to the beach collecting crustaceans in his native Australia, to his undergraduate and PhD work in zoology and biology at the University of Queensland. He has collected specimens all over the world, from Australia to Europe to North and South America.

Until now, he has never had ...

Athens, Ga. – More people are better off thanks to the impact of an influx of direct-to-consumer advertising spending than they would be without those marketing efforts, according to a study recently published by Jayani Jayawardhana, an assistant professor in the University of Georgia College of Public Health.

The multi-year study focused on advertising efforts surrounding cholesterol-reducing prescription medications. Jayawardhana found increased levels of consumer welfare due to direct-to-consumer advertising than when compared to situations without this type of marketing. ...

Call it "PAC-MAN, the Sequel." Scientists with NASA's Cassini mission have spotted a second feature shaped like the 1980s video game icon in the Saturn system, this time on the moon Tethys.

The pattern appears in thermal data obtained by Cassini's composite infrared spectrometer, with warmer areas making up the PAC-MAN shape.

"Finding a second PAC-MAN in the Saturn system tells us that the processes creating these 'PAC-MEN' are more widespread than previously thought," said Dr. Carly Howett, the lead author of a recently published paper in the journal Icarus. "The Saturn ...

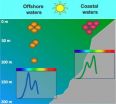

An international team of biologists led by Indiana University's David M. Kehoe has identified both the enzyme and molecular mechanism critical for controlling a chameleon-like process that allows one of the world's most abundant ocean phytoplankton, once known as blue-green algae, to maximize light harvesting for photosynthesis.

Responsible for contributing about 20 percent of the total oxygen production on the planet, the cyanobacteria Synechococcus uses its own unique form of a sophisticated response called chromatic acclimation to fine tune the absorption properties ...

Implementation of the Affordable Care Act – now assured by the re-election of President Obama – is expected to result in up to 50 million currently uninsured Americans acquiring some type of health insurance coverage. But a study by researchers at the Mongan Institute for Health Policy at Massachusetts General Hospital (MGH) finds that a significant percentage of the primary care physicians most likely to care for newly insured patients may be not be accepting new patients. The investigators note that strategies designed to increase and support these "safety-net" physicians ...

Shedding light on the limits of life in extreme environments, scientists have discovered abundant and diverse metabolically active bacteria in the brine of an Antarctic lake sealed under more than 65 feet of ice.

The finding, described in this week's issue of the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, is surprising because previous studies indicate that the brine has been isolated from the surface environment -- and external sources of energy -- for at least 2,800 years, according to two of the report's authors, Peter Doran and Fabien Kenig, both professors ...

You could call this "Pac-Man, the Sequel." Scientists with NASA's Cassini mission have spotted a second feature shaped like the 1980s video game icon in the Saturn system, this time on the moon Tethys. (The first was found on Mimas in 2010). The pattern appears in thermal data obtained by Cassini's composite infrared spectrometer, with warmer areas making up the Pac-Man shape.

"Finding a second Pac-Man in the Saturn system tells us that the processes creating these Pac-Men are more widespread than previously thought," said Carly Howett, the lead author of a paper recently ...

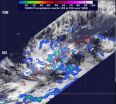

The twenty-sixth tropical cyclone of the western North Pacific Ocean season formed and has some areas of heavy rain, according to data from NASA's TRMM satellite. Tropical Depression 26W is threatening islands within Micronesia and warnings and watches are currently in effect.

Micronesia is a region in the western North Pacific Ocean made up of thousands of small islands. West of the region is the Philippines, while Indonesia is located to the southwest.

NASA's Tropical Rainfall Measuring Mission (TRMM) satellite passed over Tropical Depression 26W on Nov. 26 at 0526 ...

CHICAGO – The radiation dose to areas of the body near the breast during mammography is negligible, or very low, and does not result in an increased risk of cancer, according to a study presented today at the annual meeting of the Radiological Society of North America (RSNA). The results suggest that the use of thyroid shields during mammography is unnecessary.

"Thyroid shields can impede good mammographic quality and, therefore, are not recommended during mammography," said Alison L. Chetlen, D.O., assistant professor of radiology at Penn State Hershey Medical Center.

During ...