(Press-News.org) They say that the eyes are the windows to the soul. However, to get a real idea of what a person is up to, according to UC Santa Barbara researchers Miguel Eckstein and Matt Peterson, the best place to check is right below the eyes. Their findings are published in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences.

"It's pretty fast, it's effortless –– we're not really aware of what we're doing," said Miguel Eckstein, professor of psychology in the Department of Psychological & Brain Sciences. Using an eye tracker and more than 100 photos of faces and participants, Eckstein and graduate research assistant Peterson followed the gaze of the experiment's participants to determine where they look in the first crucial moment of identifying a person's identity, gender, and emotional state.

"For the majority of people, the first place we look at is somewhere in the middle, just below the eyes," Eckstein said. One possible reason could be that we are trained from youth to look there, because it's polite in some cultures. Or, because it allows us to figure out where the person's attention is focused.

However, Peterson and Eckstein hypothesize that, despite the ever-so-brief –– 250 millisecond –– glance, the relatively featureless point of focus, and the fact that we're usually unaware that we're doing it, the brain is actually using sophisticated computations to plan an eye movement that ensures the highest accuracy in tasks that are evolutionarily important in determining flight, fight, or love at first sight.

"When you look at a scene, or at a person's face, you're not just using information right in front of you," said Peterson. The place where one's glance is aimed is the place that corresponds to the highest resolution in the eye –– the fovea, a slight depression in the retina at the back of the eye –– while regions surrounding the foveal area –– the periphery –– allow access to less spatial detail.

However, according to Peterson, at a conversational distance, faces tend to span a larger area of the visual field. There is information to be gleaned, not just from the face's eyes, but also from features like the nose or the mouth. But when participants were directed to try to determine the identity, gender, and emotion of people in the photos by looking elsewhere –– the forehead, the mouth, for instance –– they did not perform as well as they would have by looking close to the eyes.

Using a sophisticated algorithm, which mimics the varying spatial detail of human processing across the visual field and integrates all information to make decisions, allowed Peterson and Eckstein to predict what would be the best place within the faces to look for each of these perceptual tasks. They found that these predicted places varied moderately across tasks, and closely corresponded to where humans actually do look.

At least for the three important tasks investigated –– identity, emotion, and gender –– below the eyes is the optimal place to look, say the scientists, because it allows one to read information from as many features of the face as possible.

"What the visual system is adept at doing is taking all those pieces of information from your face and combining them in a statistical manner to make a judgment about whatever task you're doing," said Eckstein. The area around the eyes contains minute bits of important information, which require the high resolution processing close to the fovea, whereas features like the mouth are larger and can be read without a direct gaze.

The study shows that the ability to learn optimal rapid eye movement for evolutionarily important perceptual tasks is inherent in humans; however, say the scientists, it is not necessarily consistent behavior for everybody. Eckstein's lab is currently involved in studying a small subset of people who do not look just below the eyes to identify a person. Other researchers have shown that East Asians, for instance, tend look lower on the face when identifying a person's face.

The research by Peterson and Eckstein has resulted in sophisticated new algorithms to model optimal gaze patterns when looking at faces. The algorithms could potentially be used to provide insight into conditions like schizophrenia and autism, which are associated with uncommon gaze patterns, or prosopagnosia –– an inability to recognize someone by his or her face.

INFORMATION:

To get the best look at a person's face, look just below the eyes, according to UCSB researchers

2012-11-27

ELSE PRESS RELEASES FROM THIS DATE:

Penn researchers make flexible, low-voltage circuits using nanocrystals

2012-11-27

PHILADELPHIA — Electronic circuits are typically integrated in rigid silicon wafers, but flexibility opens up a wide range of applications. In a world where electronics are becoming more pervasive, flexibility is a highly desirable trait, but finding materials with the right mix of performance and manufacturing cost remains a challenge.

Now a team of researchers from the University of Pennsylvania has shown that nanoscale particles, or nanocrystals, of the semiconductor cadmium selenide can be "printed" or "coated" on flexible plastics to form high-performance electronics.

The ...

Did you see that? How could you miss it?

2012-11-27

You may have received CPR training some time ago, but would you remember the proper technique in an emergency? Would you know what to do in the event of an earthquake or a fire? A new UCLA psychology study shows that people often do not recall things they have seen — or at least walked by — hundreds of times.

For the study, 54 people who work in the same building were asked if they knew the location of the fire extinguisher nearest their office. While many of the participants had worked in their offices for years and had passed the bright red extinguishers several times ...

Study advances use of stem cells in personalized medicine

2012-11-27

Johns Hopkins researchers report concrete steps in the use of human stem cells to test how diseased cells respond to drugs. Their success highlights a pathway toward faster, cheaper drug development for some genetic illnesses, as well as the ability to pre-test a therapy's safety and effectiveness on cultured clones of a patient's own cells.

The project, described in an article published November 25 on the website of the journal Nature Biotechnology, began several years ago, when Gabsang Lee, D.V.M., Ph.D., an assistant professor at the Johns Hopkins University School ...

Genome decoded: Scientists find clues to more disease-resistant watermelons

2012-11-27

ITHACA, N.Y. – Are juicier, sweeter, more disease-resistant watermelons on the way? An international consortium of more than 60 scientists from the United States, China, and Europe has published the genome sequence of watermelon (Citrullus lanatus) — information that could dramatically accelerate watermelon breeding toward production of a more nutritious, tastier and more resistant fruit. The watermelon genome sequence was published in the Nov. 25 online version of the journal Nature Genetics.

The researchers discovered that a large portion of disease resistance genes ...

Rapid changes in climate don't slow some lizards

2012-11-27

DURHAM, N.C. -- One tropical lizard's tolerance to cold is stiffer than scientists had suspected.

A new study shows that the Puerto Rican lizard Anolis cristatellus has adapted to the cooler winters of Miami. The results also suggest that this lizard may be able to tolerate temperature variations caused by climate change.

"We are not saying that climate change is not a problem for lizards. It is a major problem. However, these findings indicate that the thermal physiology of tropical lizards is more easily altered than previously proposed," said Duke biologist Manuel ...

Metabolic protein launches sugar feast that nurtures brain tumors

2012-11-27

HOUSTON - Researchers at The University of Texas MD Anderson Cancer Center have tracked down a cancer-promoting protein's pathway into the cell nucleus and discovered how, once there, it fires up a glucose metabolism pathway on which brain tumors thrive.

They also found a vital spot along the protein's journey that can be attacked with a type of drug not yet deployed against glioblastoma multiforme, the most common and lethal form of brain cancer. Published online by Nature Cell Biology, the paper further illuminates the importance of pyruvate kinase M2 (PKM2) in cancer ...

American University biologist discovers new crab species

2012-11-27

Areopaguristes tudgei. That's the name of a new species of hermit crab recently discovered on the barrier reef off the coast of Belize by Christopher Tudge, a biology professor at American University in Washington, D.C.

Tudge has been interested in biology his whole life, from boyhood trips to the beach collecting crustaceans in his native Australia, to his undergraduate and PhD work in zoology and biology at the University of Queensland. He has collected specimens all over the world, from Australia to Europe to North and South America.

Until now, he has never had ...

Study links improved consumer welfare to increased prescription drug advertising efforts

2012-11-27

Athens, Ga. – More people are better off thanks to the impact of an influx of direct-to-consumer advertising spending than they would be without those marketing efforts, according to a study recently published by Jayani Jayawardhana, an assistant professor in the University of Georgia College of Public Health.

The multi-year study focused on advertising efforts surrounding cholesterol-reducing prescription medications. Jayawardhana found increased levels of consumer welfare due to direct-to-consumer advertising than when compared to situations without this type of marketing. ...

SwRI team reports Cassini finds a video gamer's paradise at Saturn

2012-11-27

Call it "PAC-MAN, the Sequel." Scientists with NASA's Cassini mission have spotted a second feature shaped like the 1980s video game icon in the Saturn system, this time on the moon Tethys.

The pattern appears in thermal data obtained by Cassini's composite infrared spectrometer, with warmer areas making up the PAC-MAN shape.

"Finding a second PAC-MAN in the Saturn system tells us that the processes creating these 'PAC-MEN' are more widespread than previously thought," said Dr. Carly Howett, the lead author of a recently published paper in the journal Icarus. "The Saturn ...

IU-led team uncovers process for chameleon-like changes in world's most abundant phytoplankton

2012-11-27

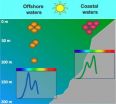

An international team of biologists led by Indiana University's David M. Kehoe has identified both the enzyme and molecular mechanism critical for controlling a chameleon-like process that allows one of the world's most abundant ocean phytoplankton, once known as blue-green algae, to maximize light harvesting for photosynthesis.

Responsible for contributing about 20 percent of the total oxygen production on the planet, the cyanobacteria Synechococcus uses its own unique form of a sophisticated response called chromatic acclimation to fine tune the absorption properties ...