(Press-News.org) Climate scientists are still grappling with one of the main questions of modern times: how high will global temperatures rise if the atmospheric concentration of carbon dioxide doubles. Many researchers are turning to the past because it holds clues to how nature reacted to climate change before the anthropogenic impact. The divergent results of this research, however, have made it difficult to make precise predictions about the impact of increased carbon dioxide on future warming. An international team of scientists have evaluated previously published estimates and assigned them consistent categories and terminology. This process should assist in limiting the range of estimates and make it easier to compare data from past climate changes and projections about future warming. The group has presented its new method in the current edition of the journal Nature.

The research group summarized, classified and compared data from more than 20 studies to make a potential prognosis about the expected future rise in the world's temperature. In these palaeoclimate studies climate sensitivity has been reconstructed on the basis of data derived from ice and sediment core. Climate sensitivity is a key parameter in the study of climate change. It describes the rise of the mean temperature of the earth's surface due to changes in the climate system. Specifically, its value represents the increase in global temperatures calculated by climate models, if the carbon dioxide content in the atmosphere doubles. Here, models were initialised with pre-industrial carbon dioxide concentrations.

The team was then faced with the challenge of comparing the assembled studies. Each study spoke of "climate sensitivity", but not all took the same factors into account. "We had to elaborate all the different assumptions and uncertainties, such as which studies look exclusively at carbon dioxide and which considered other greenhouse gases such as methane or the effect of reflection, the so called albedo, from ice surfaces. Only then could we compare the data. We also calculated the climate sensitivity data if we only considered greenhouse gases like carbon dioxide or added in albedo", explained Dr Peter Köhler, one of the article's main authors and climatologist at the Alfred Wegener Institute for Polar and Marine Research, part of the Helmholtz Association.

The research group was able to use its new method to differentiate ten different kinds of climate sensitivity. In a second phase of the project, they then worked on devising consistent terminology and concrete definitions. The new classification system should prevent future researchers from publishing widely divergent estimates of climate sensitivity based on differing assumptions. "Ideally, it should be clear from the start of a study what kind of climate sensitivity is being addressed. The factors considered by the researchers to be driving temperature change should be clear from the language used. Our terminology offers a conceptual framework to calculate climate sensitivity based on past climate data. We hope that this will improve evaluation of future climate projections", adds Köhler.

This work represents a significant advance for climatology. It is the first summary of what scientists have been able to reconstruct about climate sensitivity based on data from the past 65 million years and the assumptions that were behind the data. It also demonstrates that the climate forecasts in the IPCC reports agreed with the estimates of how nature has reacted to changes in the climate through the course of the earth's history.

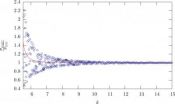

The research team has not, however, achieved one of its goals. "We had hoped to limit the range of current assumptions about climate sensitivity. In its last report, the IPCC summarised that the global temperature would rise 2.1 to 4.4 degrees C if the atmospheric carbon dioxide level rises to double the pre-industrial values. As it turns out, our climate sensitivity values are currently within this same range" says Dr Köhler.

Further open questions will have to be addressed in order to obtain more precise figures. Scientists know, for example, that climate sensitivity depends on the predominant background climate at the time, i.e. whether climate is in an ice age or a warm age. But exactly how this background climate impacts climate sensitivity still has to be answered. The climatologists behind this study hope that the new conceptual framework will push further research in this direction.

The article is the outcome of a three-day colloquium held last year at the Royal Netherlands Academy of Arts and Sciences in Amsterdam, attended by more than 30 specialists in the field.

###

The original article is entitled "Making sense of palaeoclimate sensitivity" and appeared in the 29 November issue of Nature. (doi: 10.1038/nature11574), Vol 491, pages 683-691.

New approach allows past data to be used to improve future climate projections

2012-11-29

ELSE PRESS RELEASES FROM THIS DATE:

'Dark core' may not be so dark after all

2012-11-29

ATHENS, Ohio (Nov. 29, 2012)—Astronomers were puzzled earlier this year when NASA's Hubble Space Telescope spotted an overabundance of dark matter in the heart of the merging galaxy cluster Abell 520. This observation was surprising because dark matter and galaxies should be anchored together, even during a collision between galaxy clusters.

Astronomers have abundant evidence that an as-yet-unidentified form of matter is responsible for 90 percent of the gravity within galaxies and clusters of galaxies. Because it is detected via its gravity and not its light, they call ...

The future looks bright: ONR, marines eye solar energy

2012-11-29

ARLINGTON, Va. —The Office of Naval Research (ONR) is looking to the sun for energy in an effort to help Marines do away with diesel-guzzling generators now used in combat outposts, officials announced Nov. 29.

The Renewable Sustainable Expeditionary Power (RSEP) program seeks to create a transportable renewable hybrid system that can provide Marines with electricity for a 15-day mission without relying on fuel resupply convoys that often become targets for adversaries.

"This program takes on a number of power-related challenges and ultimately will allow the Marine ...

Mild vibrations may provide some of the same benefits to obese people as exercise

2012-11-29

Bethesda, MD—If you're looking to get some of the benefits of exercise without doing the work, here's some good news. A new research report published online in The FASEB Journal shows that low-intensity vibrations led to improvements in the immune function of obese mice. If the same effect can be found in people, this could have clinical benefits for obese people suffering from a wide range of immune problems related to obesity.

"This study demonstrates that mechanical signals can help restore an immune system compromised by obesity," said Clinton Rubin, Ph.D., study ...

Oceanic crust breakthrough: Solving a magma mystery

2012-11-29

Washington, D.C. — Oceanic crust covers two-thirds of the Earth's solid surface, but scientists still don't entirely understand the process by which it is made. Analysis of more than 600 samples of oceanic crust by a team including Carnegie's Frances Jenner reveals a systemic pattern that alters long-held beliefs about how this process works, explaining a crucial step in understanding Earth's geological deep processes. Their work is published in Nature on November 29.

Magmas generated by melting of the Earth's mantle rise up below the oceanic crust and erupt on the Earth's ...

Children with higher intelligence less likely to report chronic widespread pain in adulthood

2012-11-29

Philadelphia, PA, November 29, 2012 – A UK-based study team has determined that there is a correlation between childhood intelligence and chronic widespread pain (CWP) in adulthood, according to a new study published in the December issue of PAIN®. About 10-15 percent of adults report CWP, a common musculoskeletal complaint that tends to occur more frequently among women and those from disadvantaged socioeconomic backgrounds. CWP is a core symptom of fibromyalgia and is one of the most common reasons for consulting a rheumatologist.

"One psychological factor that could ...

Canada's first liver cell transplant takes place in Calgary

2012-11-29

CALGARY – A three-month-old Winnipeg girl has become the first patient in Canada to receive an experimental and potentially life-saving form of therapy to improve the function of her liver.

Physicians at Alberta Children's Hospital, led by medical geneticist Dr. Aneal Khan, successfully completed a series of liver cell transplants earlier this month on patient Nazdana Ali.

Nazdana was born last August with a Urea Cycle Disorder (UCD), a genetic disease that causes ammonia to build up in the body that, if untreated, would lead to brain damage and death. Ammonia is ...

Sources of E. coli are not always what they seem

2012-11-29

This press release is available in Spanish.

U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA) scientists have identified sources of Escherichia coli bacteria that could help restore the reputation of local livestock. Studies by Agricultural Research Service (ARS) scientist Mark Ibekwe suggest that in some parts of California, pathogens in local waterways are more often carried there via runoff from urban areas, not from animal production facilities.

ARS is USDA's chief intramural scientific research agency, and this work supports the USDA priority of ensuring food safety.

Even ...

The beginning of everything: A new paradigm shift for the infant universe

2012-11-29

A new paradigm for understanding the earliest eras in the history of the universe has been developed by scientists at Penn State University. Using techniques from an area of modern physics called loop quantum cosmology, developed at Penn State, the scientists now have extended analyses that include quantum physics farther back in time than ever before -- all the way to the beginning. The new paradigm of loop quantum origins shows, for the first time, that the large-scale structures we now see in the universe evolved from fundamental fluctuations in the essential quantum ...

Precisely engineering 3-D brain tissues

2012-11-29

CAMBRIDGE, MA -- Borrowing from microfabrication techniques used in the semiconductor industry, MIT and Harvard Medical School (HMS) engineers have developed a simple and inexpensive way to create three-dimensional brain tissues in a lab dish.

The new technique yields tissue constructs that closely mimic the cellular composition of those in the living brain, allowing scientists to study how neurons form connections and to predict how cells from individual patients might respond to different drugs. The work also paves the way for developing bioengineered implants to replace ...

Running too far, too fast, and too long speeds progress 'to finish line of life'

2012-11-29

Vigorous exercise is good for health, but only if it's limited to a maximum daily dose of between 30 and 50 minutes, say researchers in an editorial published online in Heart.

The idea that more and more high intensity exercise, such as marathons, can only do you good, is a myth say the US cardiologists, and the evidence shows that it's likely to more harm than good to your heart.

"If you really want to do a marathon or full distance triathlon, etc, it may be best to do just one or a few and then proceed to safer and healthier exercise patterns," they warn.

"A routine ...