Clinical trial hits new target in war on breast cancer

Prostate cancer drug shows promise in triple-negative and estrogen-positive breast cancer

2012-12-03

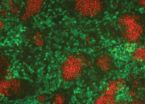

(Press-News.org) Breast cancers are defined by their drivers – estrogen and progesterone receptors (ER and PR) and HER2 are the most common, and there are drugs targeting each. When breast cancer has an unknown driver, it also has fewer treatment options – this aggressive form of breast cancer without ER, PR or HER2, which was thought not to be driven by hormones, is known as triple negative. A decade ago, work at the University of Colorado Cancer Center added another potential driver to the list – the androgen receptor – and this week marks a major milestone in a clinical trial targeting this cause of breast cancer growth.

In fact, 75 percent of all breast cancers and about 20 percent of triple negative cancers are positive for the androgen receptor. Blocking the androgen receptor may stop the growth of some triple negative breast cancers – these aggressive cancers for which chemotherapy, radiation, surgery and hope have long been the only treatments.

"This work is a concise example of modern cancer science in action. We noticed something in the clinic, worked on it in the lab, and now are happy to report the lab work is once again back in the clinic where it has the very real potential to benefit patients," says Anthony Elias, MD, breast cancer program director at CU Cancer Center.

The work started in 2001 when Elias took the clinical observation of estrogen-positive breast cancers that responded poorly or only very temporarily to estrogen-blocking treatments, to colleague Jennifer Richer, PhD, co-director of the CU Cancer Center Tissue Processing and Procurement Core. In these cases, something else was driving the cancer. What was the pathway? Richer showed that it was the androgen receptor.

Androgens including testosterone have long been implicated as a driver of prostate cancer and so drugs targeting both the body's production of androgens and cancer cells' ability to use the hormone were already in the development pipeline. Richer started with cell culture and animal model work on a then-experimental drug by the company Medivation known as MDV-3100.

"Normally, the way these hormones work is by attaching to receptors in the cell cytoplasm, at which point the receptor draws itself and the hormone molecule inside the nucleus where it regulates genes," Richer says. The genes regulated by these hormones tell breast cancer cells to survive and reproduce beyond control. The drug MDV-3100, now known as Enzalutamide, which recently gained FDA approval for use with prostate cancer, makes androgen receptors unable to go into a cell's nucleus – and so the message of growth never gets delivered.

"Interestingly, it seems that estrogen-positive breast cancers are susceptible to the same drug," Richer says, explaining that something about the way the signal of estrogen is transmitted inside a cell's nucleus requires the (counterintuitive) presence of androgen receptors in the nucleus, too.

And so Enzalutamide has many potential uses in the treatment of breast cancer: as a first-line drug against androgen receptor-positive cancers with or without additional hormonal drivers, as a second-line drug against tumors that have mutated away from estrogen- or HER2-dependence by adopting androgen-dependence, in combination with drugs that target these other hormones to disallow cancer from mutating toward androgen-dependence in the first place, or perhaps in addition to or instead of existing treatments for estrogen-positive breast cancers – which seem susceptible to this anti-androgen therapy.

This week, after seeing, "no additional toxicities," Elias expects an ongoing Phase I clinical trial of Enzalutamide for triple-negative breast cancers to flip to a Phase II trial – from proving safety to demonstrating results. In addition to the CU Cancer Center, the trial is being offered at Memorial Sloan-Kettering Cancer Center and the Karmanos Cancer Institute. Richer and Elias will present additional findings from their work with androgen-positive breast cancer at the San Antonio Breast Cancer Symposium in December and will hear about a major invited grant proposal to the U.S. Department of Defense the same month.

"It's an exciting time for breast cancer research," Elias says. "We should know soon if we have a viable new target in breast cancer treatment."

Along with validating a new target, Richer and Elias may soon provide a powerful new treatment for breast cancers that evade current therapies.

INFORMATION:

END

ELSE PRESS RELEASES FROM THIS DATE:

2012-12-03

LA JOLLA, Calif., December 3, 2012 – An embryo is an amazing thing. From just one initial cell, an entire living, breathing body emerges, full of working cells and organs. It comes as no surprise that embryonic development is a very carefully orchestrated process—everything has to fall into the right place at the right time. Developmental and cell biologists study this very thing, unraveling the molecular cues that determine how we become human.

"One of the first, and arguably most important, steps in development is the allocation of cells into three germ layers—ectoderm, ...

2012-12-03

"Understanding peoples' attitudes about whether states of being should be considered diseases can inform social discourse regarding a number of contentious social and health public policy issues," says Kari Tikkinen, MD, PhD, corresponding author of the FIND Survey.

All Finns think that myocardial infarction, breast cancer, malaria and pneumonia are diseases. People are equally unanimous that wrinkles, grief and homosexuality are not diseases. What about drug addiction or absence of sexual desire? Or erectile dysfunction, infertility or obesity?

"The word disease ...

2012-12-03

The University of Granada researchers are pioneers in the application of thermography to the field Psychology. Thermography is a technique based on determining body temperature.

When a person lies they suffer a "Pinocchio effect", which is an increase in the temperature around the nose and in the orbital muscle in the inner corner of the eye. In addition, when we perform a considerable mental effort our face temperature drops and when we have an anxiety attack our face temperature raises. These are some of the conclusions drawn in this pioneer study conducted at the University ...

2012-12-03

December 3, 2012, Hong Kong and Shenzhen, China – The 7th International Conference on Genomics and Bio-IT APAC 2012, organized by BGI, the world's largest genomics organization, successfully concluded with numerous updates on on-going research applying today's latest sequencing and bioinformatics technologies to a new paradigm of human diseases and to enhancing global agriculture development. The three-day conference, held in Hong Kong, also brought new insights into Bio-cloud and big data management. More than 300 participants attended this top-grade international conference.

The ...

2012-12-03

As the nights draw in and the temperature begins to drop, many of us will be thinking of ways to warm up on the dark winter nights. However, few would think that remembering days gone by would be an effective way of keeping warm.

But research from the University of Southampton has shown that feeling nostalgic can make us feel warmer.

The study, published in the journal Emotion, investigated the effects of nostalgic feelings on reaction to cold and the perception of warmth. The volunteers, from universities in China and the Netherlands, took part in one of five studies. ...

2012-12-03

Researchers have identified four new genetic regions that influence birth weight, providing further evidence that genes as well as maternal nutrition are important for growth in the womb. Three of the regions are also linked to adult metabolism, helping to explain why smaller babies have higher rates of chronic diseases later in life.

It has been known for some time that babies born with a lower birth weight are at higher risk of chronic diseases such as type 2 diabetes and cardiovascular disease. Three genetic regions have already been identified that influence birth ...

2012-12-03

This press release is available in Spanish.

Information and Communication Technologies (ICT) present tremendous potential in the field of healthcare, according to the researchers. "ICTs are going to contribute to a change in focus in aid and health services," comments Jesús Espinosa, CEO of IonIDE Telematics. According to accreditation and standardization associations, Spain is a leader in the management of clinical processes, because it has the greatest number of hospitals that have adopted electronic medical record (EMR). This computerized registry of patients' social, ...

2012-12-03

Hybrid plants provide much higher yield than their homozygous parents. Plant breeders have known this for more than 100 years and used this effect called heterosis for richer harvests. Until now, science has puzzled over the molecular processes underlying this phenomenon. Researchers at the University of Bonn and partners from Tübingen and the USA have now decoded one possible mechanism in corn roots. More genes are active in hybrid plants than in their homozygous parents. This might increase growth and yield of the corn plants. The results are published in the renowned ...

2012-12-03

Six years of observations by ESA's Venus Express have shown large changes in the sulphur dioxide content of the planet's atmosphere, and one intriguing possible explanation is volcanic eruptions.

The thick atmosphere of Venus contains over a million times as much sulphur dioxide as Earth's, where almost all of the pungent, toxic gas is generated by volcanic activity.

Most of the sulphur dioxide on Venus is hidden below the planet's dense upper cloud deck, because the gas is readily destroyed by sunlight.

That means any sulphur dioxide detected in Venus' upper atmosphere ...

2012-12-03

More than a million people die each year of malaria caused by different strains of the Plasmodium parasite transmitted by the Anopheles mosquito. The medical world has yet to find an effective vaccine against the deadly parasite, which mainly affects pregnant women and children under the age of five. By figuring out how the most dangerous strain evades the watchful eye of the immune system, researchers from the Hebrew University of Jerusalem have now paved the way for the development of new approaches to cure this acute infection.

Upon entering the bloodstream, the Plasmodium ...

LAST 30 PRESS RELEASES:

[Press-News.org] Clinical trial hits new target in war on breast cancer

Prostate cancer drug shows promise in triple-negative and estrogen-positive breast cancer