(Press-News.org) No man is an island, entire of itself, said poet John Donne. And no atom neither. Even in the middle of intergalactic space, atoms feel the electromagnetic field---also known as the cosmic microwave background---left over by the Big Bang. The cosmos is filled with interactions that remind atoms they are not alone. Stray electric fields, say from a nearby electronic device, will also slightly adjust the internal energy levels of atoms, a process called the Stark effect. Even the universal vacuum, presumably empty of any energy or particles, can very briefly muster virtual particles that buffet electrons inside atoms, further shifting their energies; this form of self-interaction is known as the Lamb shift.

A new calculation by scientists at the Joint Quantum Institute (JQI) and the University of Delaware shows how still another influence, the warmth thrown off by nearby objects, can shift energy levels. Uncertainties in this "blackbody radiation shift" will soon impose limits on the accuracy of the best atomic clocks. Theoretical work on this subject will give scientists extra confidence when they come to redefine the second in coming years, a recalibration based on how ultracold atoms behave while sitting in special traps.

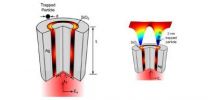

Modern timekeeping consists nowadays in reliably counting the cycles of light pouring out of those atoms and, more basic still, knowing what the atoms' intrinsic energy levels should be once all external influences are taken into account. On the experimental side, scientists slow the atoms to a near standstill in traps in order to minimize Doppler effects from the emitted light. This, and the ability to detect and count light oscillations at ever shorter wavelengths ---has led to atomic clocks with uncertainties as small as one part in 1017.

This research is Nobel-rich territory. To say nothing of earlier Nobels for atom cooling, the move from microwaves as the atomic "escapement" for clocks to light in the optical range (harder to measure but offering a precision hundreds of thousands of times better) earned several scientists the 2005 Nobel in Physics. One of 2012's Nobelists, David Wineland, is a pioneer in exploiting the properties of single ion held in a trap to develop clocks of the highest stability.

The precision of the clocks, however, is no better than knowledge of the internal energy levels of the atoms themselves, whether they are single ions or a gas of neutral atoms held in space by a network of laser beams---an arrangement called an optical lattice.

Some of the things that impose unwanted shifts on the atoms in a lattice, such as inter-atom collisions or the Stark effect, can be controlled. According to JQI Fellow Charles Clark, one of the largest irreducible parts in the uncertainty budget of an atomic clock is the blackbody radiation emitted by the very chamber enclosing the atoms. The atoms in the lattice might, by virtue of an elaborate cooling process, be at milli-kelvin or even micro-kelvin temperatures, but the surrounding vacuum chamber is generally at room temperature. One of the basic laws of thermodynamics says that material objects radiate heat---the higher the temperature the higher-energy the radiation. This shift is hard to measure experimentally and hard to calculate theoretically.

Coming to grips with this faint form of influence is the purpose of a new paper in the journal Physical Review Letters (**). Clark and his co-authors Marianna Safronova (a JQI Adjunct Fellow) and Sergey Porsev of the University of Delaware, look specifically at how ytterbium atoms are affected by blackbody radiation.

The rare-earth element ytterbium (Yb) is valued not so much for its mechanical properties but for its complement of internal energy levels. "A particular transition in Yb atoms, at a wavelength of 578 nm, currently provides one of the world's most accurate optical atomic frequency standards," said Safronova.

Although only important at a precision level of a part in 1015, accurate knowledge of the blackbody shift is more pertinent now that clocks are closing in on the part-per-1018 level of precision. That is, the uncertainty in the blackbody shift must be comparable to (and eventually lower than) the desired uncertainty of the clock. The new calculation by Safronova, Clark, and Porsev is the best yet since it includes the most complete treatment of the electron-electron correlations within the Yb atoms.

Clark estimates that the amount of uncertainty achieved in the value of an atomic energy level---about 2 times 10-18 --- corresponds to a clock uncertainty of about one second over the lifetime of the universe so far, 15 billion years.

The authors also studied the long-distance interactions among the Yb atoms and atoms of other species as well. This is critical to understanding the physics of dilute gas mixtures in general. Such mixtures are of interest, for example, in studying such things as quantum dipolar material (molecules which, though neutral, possess an electric dipole moment) and many-body quantum simulation. Besides applications in timekeeping and the study of ultracold chemistry, the results of the present work are important for the measurement of the weak force (through subtle parity effects---the process by which nature can tell left from right) and the search for the new physics beyond the standard model of the electroweak interactions.

INFORMATION:

(*)The Joint Quantum Institute is operated jointly by the National Institute of Standards and Technology in Gaithersburg, MD and the University of Maryland in College Park.

(**) "Ytterbium in quantum gases and atomic clocks: van der Waals interactions and blackbody shifts,"

M. S. Safronova, S. G. Porsev, and Charles W. Clark, Physical Review Letters, 7 December 2012.

Press contact at JQI: Phillip F. Schewe, pschewe@umd.edu, 301-405-0989. http://jqi.umd.edu/

Quantum thermodynamics

A better understanding of how atoms soak up their surroundings

2012-12-05

ELSE PRESS RELEASES FROM THIS DATE:

Hogging the spotlight: South Farms pig gets international attention

2012-12-05

URBANA – A detailed annotation of the genome of T.J. Tabasco, a pig from the University of Illinois South Farms, is the outcome of over 10 years of work by an international consortium. It is expected to speed progress in both biomedical and agricultural research. U of I Vice President for Research Lawrence Schook said that the College of ACES played a crucial role in getting the work started.

Funding that came through ACES allowed Schook and others to put together the Swine Genome Sequencing Consortium, an alliance of university, industry, and government laboratories ...

New optical tweezers trap specimens just a few nanometers across

2012-12-05

To grasp and move microscopic objects, such as bacteria and the components of living cells, scientists can harness the power of concentrated light to manipulate them without ever physically touching them.

Now, doctoral student Amr Saleh and Assistant Professor Jennifer Dionne, researchers at the Stanford School of Engineering, have designed an innovative light aperture that allows them to optically trap smaller objects than ever before – potentially just a few atoms in size.

The process of optical trapping – or optical tweezing, as it is often known – involves sculpting ...

Brain stimulation may buffer feelings of social pain

2012-12-05

Paolo Riva of the University of Milano-Bicocca and colleagues wanted to examine whether there might be a causal relationship between activity in the right ventrolateral prefrontal cortex (rVLPFC) – known to be involved in the regulation of physical pain and negative expressions of emotion – and experiences of social pain. Their findings are published in Psychological Science, a journal of the Association for Psychological Science.

The researchers recruited 79 university students to take part in a "mental visualization exercise." They used a constant-current regulator ...

Antiretroviral treatment for HIV reduces food insecurity, reports AIDS Journal

2012-12-05

Philadelphia, Pa. (December 4, 2012) – Can treatment with modern anti-HIV drugs help fight hunger for HIV-infected patients in Africa? Starting antiretroviral therapy for HIV reduces "food insecurity" among patients in Uganda, suggests a study published online by the journal AIDS, official journal of the International AIDS Society. AIDS is published by Lippincott Williams & Wilkins, a part ofWolters Kluwer Health..

Treatment including antiretroviral therapy (ART) may lead to a "positive feedback loop" whereby improved functioning and productivity lead to increased ability ...

'Transport infrastructure' determines spread of HIV subtypes in Africa

2012-12-05

Philadelphia, Pa. (December 4, 2012) – Road networks and geographic factors affecting "spatial accessibility" have a major impact on the spread of HIV across sub-Saharan Africa, according to a study published online by the journal AIDS, official journal of the International AIDS Society. AIDS is published by Lippincott Williams & Wilkins, a part ofWolters Kluwer Health.

Using sophisticated mapping techniques and detailed databases, Dr Andrew J. Tatem of the University of Florida and colleagues have found "coherent spatial patterns in HIV-1 subtype distributions" across ...

Breath test could possibly diagnose colorectal cancer

2012-12-05

A new study published in BJS has demonstrated for the first time that a simple breath analysis could be used for colorectal cancer screening. The study is part of the "Improving Outcomes in Gastrointestinal Cancer" supplement.

Cancer tissue has different metabolism compared to normal healthy cells and produces some substances which can be detected in the breath of these patients. Analysis of the volatile organic compounds (VOCs) linked to cancer is a new frontier in cancer screening.

Led by Donato F. Altomare, MD, of the Department of Emergency and Organ Transplantation ...

Smoking may worsen hangover after heavy drinking

2012-12-05

PISCATAWAY, NJ – People who like to smoke when they drink may be at greater risk of suffering a hangover the next morning, according to a study in the January 2013 issue of the Journal of Studies on Alcohol and Drugs.

For anyone who has ever had too much to drink, that day-after combination of headache, nausea and fatigue may be a familiar feeling. But some drinkers appear hangover-resistant: about one-quarter of people who drink enough to spur a hangover in most of us don't actually develop one.

No one is sure why that is. But the new study suggests that smoking could ...

Study finds unique 'anonymous delivery' law effective in decreasing rates of neonaticide in Austria

2012-12-05

Rates of reported neonaticide have more than halved following the implementation of a unique 'anonymous delivery' law in Austria, finds a new study published today (05 December) in BJOG: An International Journal of Obstetrics and Gynaecology.

Researchers, from the Medical University of Vienna, looked at the rates of reported neonaticide (where a child is killed within the first 24 hours of birth) in Austria prior to and after the implementation of the 'anonymous delivery' law which was introduced in 2001. The law allows women access to antenatal care and to give birth ...

Consumers benefitted nearly $1.5 billion from the ACA's medical loss ratio rule in 2011

2012-12-05

New York, NY, December 5, 2012—Consumers saw nearly $1.5 billion in insurer rebates and overhead cost savings in 2011, due to the Affordable Care Act's medical loss ratio provision requiring health insurers to spend at least 80 percent of premium dollars on health care or quality improvement activities or pay a rebate to their customers, according to a new Commonwealth Fund report. Consumers with individual policies saw substantially reduced premiums when insurers reduced both administrative costs and profits to meet the new standards. While insurers in the small- and large-group ...

National Geographic unveils new phase of genographic project

2012-12-05

WASHINGTON (Dec. 5, 2012)-- The National Geographic Society today announced the next phase of its Genographic Project — the multiyear global research initiative that uses DNA to map the history of human migration. Building on seven years of global data collection, Genographic shines new light on humanity's collective past, yielding tantalizing clues about humankind's journey across the planet over the past 60,000 years.

"Our first phase drew participation from more than 500,000 participants from over 130 countries," said Project Director Spencer Wells, a population geneticist ...

LAST 30 PRESS RELEASES:

Scientists reveal our best- and worst-case scenarios for a warming Antarctica

Cleaner fish show intelligence typical of mammals

AABNet and partners launch landmark guide on the conservation of African livestock genetic resources and sustainable breeding strategies

Produce hydrogen and oxygen simultaneously from a single atom! Achieve carbon neutrality with an 'All-in-one' single-atom water electrolysis catalyst

Sleep loss linked to higher atrial fibrillation risk in working-age adults

Visible light-driven deracemization of α-aryl ketones synergistically catalyzed by thiophenols and chiral phosphoric acid

Most AI bots lack basic safety disclosures, study finds

How competitive gaming on discord fosters social connections

CU Anschutz School of Medicine receives best ranking in NIH funding in 20 years

Mayo Clinic opens patient information office in Cayman Islands

Phonon lasers unlock ultrabroadband acoustic frequency combs

Babies with an increased likelihood of autism may struggle to settle into deep, restorative sleep, according to a new study from the University of East Anglia.

National Reactor Innovation Center opens Molten Salt Thermophysical Examination Capability at INL

International Progressive MS Alliance awards €6.9 million to three studies researching therapies to address common symptoms of progressive MS

Can your soil’s color predict its health?

Biochar nanomaterials could transform medicine, energy, and climate solutions

Turning waste into power: scientists convert discarded phone batteries and industrial lignin into high-performance sodium battery materials

PhD student maps mysterious upper atmosphere of Uranus for the first time

Idaho National Laboratory to accelerate nuclear energy deployment with NVIDIA AI through the Genesis Mission

Blood test could help guide treatment decisions in germ cell tumors

New ‘scimitar-crested’ Spinosaurus species discovered in the central Sahara

“Cyborg” pancreatic organoids can monitor the maturation of islet cells

Technique to extract concepts from AI models can help steer and monitor model outputs

Study clarifies the cancer genome in domestic cats

Crested Spinosaurus fossil was aquatic, but lived 1,000 kilometers from the Tethys Sea

MULTI-evolve: Rapid evolution of complex multi-mutant proteins

A new method to steer AI output uncovers vulnerabilities and potential improvements

Why some objects in space look like snowmen

Flickering glacial climate may have shaped early human evolution

First AHA/ACC acute pulmonary embolism guideline: prompt diagnosis and treatment are key

[Press-News.org] Quantum thermodynamicsA better understanding of how atoms soak up their surroundings