(Press-News.org) Moths are able to enjoy a pollinator's buffet of flowers – in spite of being among the insect world's picky eaters – because of two distinct "channels" in their brains, scientists at the University of Washington and University of Arizona have discovered.

One olfactory channel governs innate preferences of the palm-sized hawk moths that were studied – insects capable of traveling miles in a single night in search of favored blossoms. The other allows them to learn about alternate sources of nectar when their first choices are not available.

For moths, the ability to seek and remember alternate sources of food helps them survive harsh, food-deprived conditions. Scientists knew bees could learn, but this is the first proof that moths can too.

A better understanding of the moth's neural basis of olfactory specialization and learning also might lead to insights into how human noses and brains process odor, according to Jeffrey Riffell, a UW assistant professor of biology and lead author of a paper published Thursday (Dec. 6) in Science Express, the early online edition of the journal Science. Many of the mechanisms insects use to process olfactory information are similar to humans, and moths have long served as a model system for behavior and neurobiology, he said.

The moths, Manduca sexta, are commonly called hawk moths and are found throughout North and South America. As caterpillars they are known as the tobacco hornworms – bright green, thicker than a man's thumb and one alone can eat a tomato plant to the ground. They become moths two to three inches in length and they are important pollinators of night-blooming flowers, Riffell said.

To investigate innate preferences, scent samples were collected from flowers that scientists observed were regularly visited by hawk moths in the wild. Scents were also collected from closely related flowers, but ones hawk moths tended to shun.

Analyzing the scents in the lab, the scientists found most of the preferred flowers shared a remarkably similar chemical profile dominated by certain oxygenated aromatic compounds.

It didn't matter that some of the plants evolved 10 million to 50 million years apart from each other – their scents have the same chemical composition that holds appeal for hawk moths, Riffell said.

The scientists then used electronic recorders through the moths' antennae – which in part function as their noses – to identify the olfactory channel in use when the moths were exposed to key chemicals from preferred flowers. The moths categorized, or grouped, the moth-pollinated flowers in the exact same manner in the olfactory lobe, Riffell said. Non-preferred flowers failed to activate any particular neural pathways.

To check their findings, scents of preferred and non-preferred flowers were offered to "naive" moths, those raised on a soybean diet and never seeing real flowers.

"What we found was really amazing. A naive moth will go mainly to flowers that had been attractive to moths in the wild, from flower to flower as if they were the same flower, responding in the very same manner," Riffell said. "These favored flowers look very different from each other, it's the odor that's driving the behavior."

Distinct from this channel of innate odor preferences, there appears to be another olfactory channel employed when moths learn about alternate food sources, the scientists found.

In the wild, moths go to preferred flowers but also to other flowers. The agave, or century plant, for example, is adapted for pollination by bats but it is such a cornucopia of nectar that bees, birds and other pollinators seek it out, especially in desert environments, Riffell said.

Scientists trained moths in the lab to associate sugar-water rewards with the scent of agave while recording their brain activity. They found the neural modulator octopamine is released in their brains as the signal to remember an important food resource. Further, the scientists found that learning about an alternate food source doesn't extinguish the moth's innate preferences, something that can happen with bees.

Together the two olfactory channels mean moths can survive in a changing floral environment, where at times their favored flowers might not be available, yet still maintain their innate preferences.

The approach using observations and experiments in both natural settings and labs, is one promoted by the University of Arizona's John Hildebrand, a co-author of the paper. Riffell did postdoctoral research in Hildebrand's lab.

"This study is based on observations of wild animals in the real world. We think it's critically important to know what the animals do in the natural world, not just what they do in the lab," said Hildebrand. "It's not enough for us to show what the animal can do under artificial conditions – we want to know the basis for what the animal does when it's living out in the world."

INFORMATION:

Other co-authors are Hong Lei and Leif Abrell at Arizona. Funding was provided by the National Science Foundation and the National Institutes of Health.

For more information:

Riffell, jriffell@uw.edu, 310-488-1227

Moths wired two ways to take advantage of floral potluck

2012-12-07

ELSE PRESS RELEASES FROM THIS DATE:

New study sheds light on how Salmonella spreads in the body

2012-12-07

Findings of Cambridge scientists, published today in the journal PLoS Pathogens, show a new mechanism used by bacteria to spread in the body with the potential to identify targets to prevent the dissemination of the infection process.

Salmonella enterica is a major threat to public health, causing systemic diseases (typhoid and paratyphoid fever), gastroenteritis and non-typhoidal septicaemia (NTS) in humans and in many animal species worldwide. In the natural infection, salmonellae are typically acquired from the environment by oral ingestion of contaminated water ...

Neuroscientists prove ultrasound can be tweaked to stimulate different sensations

2012-12-07

A century after the world's first ultrasonic detection device – invented in response to the sinking of the Titanic – Virginia Tech Carilion Research Institute scientists have provided the first neurophysiological evidence for something that researchers have long suspected: ultrasound applied to the periphery, such as the fingertips, can stimulate different sensory pathways leading to the brain.

And that's just the tip of the iceberg. The discovery carries implications for diagnosing and treating neuropathy, which affects millions of people around the world.

"Ideally, ...

Researchers craft tool to minimize threat of endocrine disruptors in new chemicals

2012-12-07

Researchers from North Carolina State University, the National Institute of Environmental Health Sciences and a host of other institutions have developed a safety testing system to help chemists design inherently safer chemicals and processes.

The innovative "TiPED" testing system (Tiered Protocol for Endocrine Disruption) stems from a cross-disciplinary collaboration among scientists, and can be applied at different phases of the chemical design process. The goal of the system is to help steer companies away from inadvertently creating harmful products, and thus avoid ...

Autistic adults report significant shortcomings in their health care

2012-12-07

PORTLAND, Ore. — Researchers at Oregon Health & Science University (OHSU) have found that adults with autism, who represent about 1 percent of the adult population in the United States, report significantly worse health care experiences than their non-autistic counterparts.

"Like other adults, adults on the autism spectrum need to use health care services to prevent and treat illness. As a primary care provider, I know that our health care system is not always set up to offer high-quality care to adults on the spectrum; however, I was saddened to see how large the disparities ...

Unlocking the genetic mysteries behind stillbirth

2012-12-07

Galveston, Texas — Stillbirth is a tragedy that occurs in one of every 160 births in the United States. Compounding the sadness for many families, the standard medical test used to examine fetal chromosomes often can't pin down what caused their baby to die in utero. In most cases, the cause of the stillbirth is not immediately known. The traditional way to determine what happened is to examine the baby's chromosomes using a technique called karyotyping. This method leaves much to be desired because, in many cases, it fails to provide any result at all. Today, some 25 to ...

Different genes behind same adaptation to thin air

2012-12-07

Highlanders in Tibet and Ethiopia share a biological adaptation that enables them to thrive in the low oxygen of high altitudes, but the ability to pass on the trait appears to be linked to different genes in the two groups, research from a Case Western Reserve University scientist and colleagues shows.

The adaptation is the ability to maintain a relatively low (for high altitudes) level of hemoglobin, the oxygen-carrying protein in red blood cells. Members of ethnic populations - such as most Americans - who historically live at low altitudes naturally respond to the ...

Deception can be perfected

2012-12-07

EVANSTON, Ill. --- With a little practice, one could learn to tell a lie that may be indistinguishable from the truth.

New Northwestern University research shows that lying is more malleable than previously thought, and with a certain amount of training and instruction, the art of deception can be perfected.

People generally take longer and make more mistakes when telling lies than telling the truth, because they are holding two conflicting answers in mind and suppressing the honest response, previous research has shown. Consequently, researchers in the present study ...

Gladstone scientists discover novel mechanism by which calorie restriction influences longevity

2012-12-07

SAN FRANCISCO, CA—December 6, 2012—Scientists at the Gladstone Institutes have identified a novel mechanism by which a type of low-carb, low-calorie diet—called a "ketogenic diet"—could delay the effects of aging. This fundamental discovery reveals how such a diet could slow the aging process and may one day allow scientists to better treat or prevent age-related diseases, including heart disease, Alzheimer's disease and many forms of cancer.

As the aging population continues to grow, age-related illnesses have become increasingly common. Already in the United States, ...

Attitudes predict ability to follow post-treatment advice

2012-12-07

SAN ANTONIO, TX (December 6, 2012)—Women are more likely to follow experts' advice on how to reduce their risk of an important side effect of breast cancer surgery—like lymphedema—if they feel confident in their abilities and know how to manage stress, according to new research from Fox Chase Cancer Center to be presented at the 2012 CTRC-AACR San Antonio Breast Cancer Symposium on Saturday, December 8, 2012.

These findings suggest that clinicians must do more than just inform women of the ways they should change their behavior, says Suzanne M. Miller, PhD, Professor ...

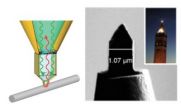

Seeing in color at the nanoscale

2012-12-07

If nanoscience were television, we'd be in the 1950s. Although scientists can make and manipulate nanoscale objects with increasingly awesome control, they are limited to black-and-white imagery for examining those objects. Information about nanoscale chemistry and interactions with light—the atomic-microscopy equivalent to color—is tantalizingly out of reach to all but the most persistent researchers.

But that may all change with the introduction of a new microscopy tool from researchers at the Department of Energy (DOE)'s Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory (Berkeley ...