(Press-News.org) In a discovery that may prove important for cognitive science, our understanding of nature and applications for robot vision, researchers at the University of Adelaide have found evidence that the dragonfly is capable of higher-level thought processes when hunting its prey.

The discovery, to be published online today in the journal Current Biology, is the first evidence that an invertebrate animal has brain cells for selective attention, which has so far only been demonstrated in primates.

Dr Steven Wiederman and Associate Professor David O'Carroll from the University of Adelaide's Centre for Neuroscience Research have been studying insect vision for many years.

Using a tiny glass probe with a tip that is only 60 nanometers wide - 1500 times smaller than the width of a human hair - the researchers have discovered neuron activity in the dragonfly's brain that enables this selective attention.

They found that when presented with more than one visual target, the dragonfly brain cell 'locks on' to one target and behaves as if the other targets don't exist.

"Selective attention is fundamental to humans' ability to select and respond to one sensory stimulus in the presence of distractions," Dr Wiederman says.

"Imagine a tennis player having to pick out a small ball from the crowd when it's traveling at almost 200kms an hour - you need selective attention in order to hit that ball back into play.

"Precisely how this works in biological brains remains poorly understood, and this has been a hot topic in neuroscience in recent years," he says.

VIDEO:

This is a video in the field showing a dragonfly on the hunt for prey -- shown at normal speed and then in slow motion. The dragonfly hovers while it...

Click here for more information.

"The dragonfly hunts for other insects, and these might be part of a swarm - they're all tiny moving objects. Once the dragonfly has selected a target, its neuron activity filters out all other potential prey. The dragonfly then swoops in on its prey - they get it right 97% of the time."

Associate Professor O'Carroll says this brain activity makes the dragonfly a more efficient and effective predator.

"What's exciting for us is that this is the first direct demonstration of something akin to selective attention in humans shown at the single neuron level in an invertebrate," Associate Professor O'Carroll says.

"Recent studies reveal similar mechanisms at work in the primate brain, but you might expect it there. We weren't expecting to find something so sophisticated in lowly insects from a group that's been around for 325 million years.

"We believe our work will appeal to neuroscientists and engineers alike. For example, it could be used as a model system for robotic vision. Because the insect brain is simple and accessible, future work may allow us to fully understand the underlying network of neurons and copy it into intelligent robots," he says.

INFORMATION:

Dragonflies have human-like 'selective attention'

2012-12-20

ELSE PRESS RELEASES FROM THIS DATE:

Origin of life emerged from cell membrane bioenergetics

2012-12-20

A coherent pathway which starts from no more than rocks, water and carbon dioxide and leads to the emergence of the strange bio-energetic properties of living cells, has been traced for the first time in a major hypothesis paper in Cell this week.

At the origin of life the first protocells must have needed a vast amount of energy to drive their metabolism and replication, as enzymes that catalyse very specific reactions were yet to evolve. Most energy flux must have simply dissipated without use.

So where did it all that energy come from on the early Earth, and how ...

A urine test for a rare and elusive disease

2012-12-20

Boston, Mass.—A set of proteins detected in urine by researchers at Boston Children's Hospital may prove to be the first biomarkers for Kawasaki disease, an uncommon but increasingly prevalent disease which causes inflammation of blood vessels that can lead to enlarged coronary arteries and even heart attacks in some children. If validated in more patients with Kawasaki disease, the markers could make the disease easier to diagnose and give doctors an opportunity to start treatment earlier.

The discovery was reported online by a team led by members of the Proteomics Center ...

First ever 'atlas' of T cells in human body

2012-12-20

New York, NY (December 20, 2012) — By analyzing tissues harvested from organ donors, Columbia University Medical Center (CUMC) researchers have created the first ever "atlas" of

immune cells in the human body. Their results provide a unique view of the distribution and function of T lymphocytes in healthy individuals. In addition, the findings represent a major step toward development of new strategies for creating vaccines and immunotherapies. The study was published today in the online edition of the journal Immunity.

T cells, a type of white blood cell, play a major ...

Peel-and-Stick solar panels from Stanford engineering

2012-12-20

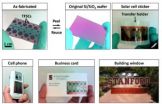

For all their promise, solar cells have frustrated scientists in one crucial regard – most are rigid. They must be deployed in stiff, often heavy, fixed panels, limiting their applications. So researchers have been trying to get photovoltaics to loosen up. The ideal: flexible, decal-like solar panels that can be peeled off like band-aids and stuck to virtually any surface, from papers to window panes.

Now the ideal is real. Stanford researchers have succeeded in developing the world's first peel-and-stick thin-film solar cells. The breakthrough is described in a ...

Cellphone, GPS data suggest new strategy for alleviating traffic tie-ups

2012-12-20

Asking all commuters to cut back on rush-hour driving reduces traffic congestion somewhat, but asking specific groups of drivers to stay off the road may work even better.

The conclusion comes from a new analysis by engineers from the Massachusetts Institute of Technology and the University of California, Berkeley, that was made possible by their ability to track traffic using commuters' cellphone and GPS signals.

This is the first large-scale traffic study to track travel using anonymous cellphone data rather than survey data or information obtained from U.S. Census ...

Research pinpoints key gene for regenerating cells after heart attack

2012-12-20

DALLAS – Dec. 20, 2012 – UT Southwestern Medical Center researchers have pinpointed a molecular mechanism needed to unleash the heart's ability to regenerate, a critical step toward developing eventual therapies for damage suffered following a heart attack.

Cardiologists and molecular biologists at UT Southwestern, teaming up to study in mice how heart tissue regenerates, found that microRNAs – tiny strands that regulate gene expression – contribute to the heart's ability to regenerate up to one week after birth. Soon thereafter the heart loses the ability to regenerate. ...

Shedding light on Anderson localization

2012-12-20

This press release is available in German.

Waves do not spread in a disordered medium if there is less than one wavelength between two defects. Physicists from the universities of Zurich and Constance have now proved Nobel Prize winner Philip W. Anderson's theory directly for the first time using the diffusion of light in a cloudy medium.

Light cannot spread in a straight line in a cloudy medium like milk because the many droplets of fat divert the light as defects. If the disorder – the concentration of defects – exceeds a certain level, the waves are no longer ...

Small wasps to control a big pest?

2012-12-20

With the purpose of developing new biological methods to control one of the major pests affecting the southwest Europe pine stands, a joint collaboration leaded by the Instituto Nacional de Investigação Agrária e Veterinária, Portugal (R. Petersen-Silva, P. Naves, E. Sousa), together with the Universidad de Barcelona, Spain (J. Pujade-Villar) and a member of the Museum and Institute of Zoology from the Polish Academy of Sciences, Poland, (S. Belokobylskij) initiated a research to detect the parasitoid guild of the Pine Wood Nematode (PWN) vector, Monochamus galloprovincialis ...

Sync to grow

2012-12-20

From a single-cell egg to a fully functional body: as embryos develop and grow, they must form organs that are in proportion to the overall size of the embryo. The exact mechanism underlying this fundamental characteristic, called scaling, is still unclear. However, a team of researchers from EMBL Heidelberg is now one step closer to understanding it. They have discovered that scaling of the future vertebrae in a mouse embryo is controlled by how the expression of some specific genes oscillates, in a coordinated way, between neighbouring cells. Published today in Nature, ...

Silver sheds light on superconductor secrets

2012-12-20

The first report on the chemical substitution, or doping, using silver atoms, for a new class of superconductor that was only discovered this year, is about to be published in EPJ B. Chinese scientists from Institute of Solid State Physics, Chinese Academy of Sciences, Hefei, discovered that the superconductivity is intrinsic rather than created by impurities in this material with a sandwich-style layered structure made of bismuth oxysulphide (Bi4O4S3).

Superconductors with a transition temperature (TC) above the boiling temperature of liquid nitrogen (77 kelvins or −196 ...