(Press-News.org) An international team, led by researchers from the University of California, San Diego School of Medicine, has discovered that "random" mutations in the genome are not quite so random after all. Their study, to be published in the journal Cell on December 21, shows that the DNA sequence in some regions of the human genome is quite volatile and can mutate ten times more frequently than the rest of the genome. Genes that are linked to autism and a variety of other disorders have a particularly strong tendency to mutate.

Clusters of mutations or "hotspots" are not unique to the autism genome but instead are an intrinsic characteristic of the human genome, according to principal investigator Jonathan Sebat, PhD, professor of psychiatry and cellular and molecule medicine, and chief of the Beyster Center for Molecular Genomics of Neuropsychiatric Diseases at UC San Diego.

"Our findings provide some insights into the underlying basis of autism—that, surprisingly, the genome is not shy about tinkering with its important genes" said Sebat. "To the contrary, disease-causing genes tend to be hypermutable."

Sebat and collaborators from Rady Children's Hospital-San Diego and BGI genome center in China sequenced the complete genomes of identical twins with autism spectrum disorder and their parents. When they compared the genomes of the twins to the genomes of their parents, the scientists identified many "germline" mutations (genetic variants that were present in both twins but not present in their mother or father).

Nearly 600 germline mutations – out of a total of 6 billion base pairs – were detected in the 10 pairs of identical twins sequenced in the study. An average of 60 mutations was detected in each child.

"The total number of mutations that we found was not surprising," said Sebat, "it's exactly what we would expect based on the normal human mutation rate." What the authors did find surprising was that mutations tended to cluster in certain regions of the genome. When the scientists looked carefully at the sites of mutation, they were able to determine the reasons why some genomic regions are "hot" while other regions are cold.

"Mutability could be explained by intrinsic properties of the genome," said UC San Diego postdoctoral researcher Jacob Michaelson, lead author of the study. "We could accurately predict the mutation rate of a gene based on the local DNA sequence and its chromatin structure, meaning the way that the DNA is packaged."

The researchers also observed some remarkable examples of mutation clustering in an individual child, where a shower of mutations occurred all at once. "When multiple mutations occur in the same place, such an event has a greater chance of disrupting a gene," said Michaelson.

The researchers surmised that hypermutable genes could be relevant to disease. When they predicted the mutation rates for genes, the authors found that genes that have been linked to autism were more mutable than the average gene, suggesting that some of the genetic culprits that contribute to autism are mutation hotspots.

The authors observed a similar trend for other disease genes. Genes associated with dominant disorders tended to be highly mutable, while mutation rates were lower for genes associated with complex traits.

"We plan to focus on these mutation hotspots in our future studies," said Sebat. "Sequencing these regions in larger numbers of patients could enable us to identify more of the genetic risk factors for autism."

INFORMATION:

The researchers at UC San Diego and Rady Children's Hospital are actively recruiting families through a genetic study called "REACH," that is funded by the Simons Foundation. For more information about this study or to get involved in autism research at UC San Diego, visit http://reachproject.ucsd.edu

Additional contributors to the published study include co-first authors Yujian Shi and Hancheng Zheng, BGI-Shenzhen, China, and Madhusudan Gujral and Dheeraj Malhotra, UC San Diego; Douglas Greer, Abhishek Bhandari, Wenting Wu, Roser Corominas, Shuli Kang, Guan Ning Lin, Jasper Estabillo, Therese Gadomski, Balvindar Singh, Natacha Akshoomoff, and Lilia M. Iakoucheva, UC San Diego School of Medicine; Xin Jin, BGI-Shenzhen and South China University of Technology, Guangzhou, China; Jian Minghan and Yingrui Li, BGI-Shenzhen; Guangming Liu, National University of Defense Technology, Changsha, Hunan, China and National Supercomputer Center, Tianjim, China; Áine Peoples, UC San Diego and Trinity College, Dublin, Ireland; Amnon Koren and Steven McCarroll, Harvard Medical School; Athurva Gore and Kun Zhang, Department of Bioengineering, UC San Diego; Christina Corsello, Rady Children's Hospital-San Diego; and Jun Wang, BGI-Shenzhen, University of Copenhagen, and the Novo Nordisk Foundation Center for Basic Metabolic Research, Copenhagen, Denmark.

The study was funded in part by grants from the National Institutes of Health (MH076431 and HG005725), the Simons Foundation Autism Research Initiative (SFARI 178088), and NIH RO1

HD065288 and NIH RO1 MH091350.

Genomic 'hotspots' offer clues to causes of autism, other disorders

2012-12-20

ELSE PRESS RELEASES FROM THIS DATE:

Preventing prostate cancer through androgen deprivation may have harmful effects

2012-12-20

PHILADELPHIA — The use of androgen deprivation therapies to prevent precancerous prostate abnormalities developing into aggressive prostate cancer may have adverse effects in men with precancers with specific genetic alterations, according to data from a preclinical study recently published in Cancer Discovery, a journal of the American Association for Cancer Research.

"The growth and survival of prostate cancer cells are very dependent on signals that the cancer cells receive from a group of hormones, called androgens, which includes testosterone," said Thomas R. Roberts, ...

Cellular patterns of development

2012-12-20

KANSAS CITY, MO – For a tiny embryo to grow into an entire fruit fly, mouse or human, the correct genes in each cell must turn on and off in precisely the right sequence. This intricate molecular dance produces the many parts of the whole creature, from muscles and skin to nerves and blood.

So what are the underlying principles of how those genes are controlled and regulated?

At the most basic level, scientists know, genes are turned on when an enzyme called RNA polymerase binds to the DNA at the beginning of a gene. The RNA polymerase copies the DNA of the gene into ...

Gladstone scientists identify powerful infection strategy of widespread and potentially lethal virus

2012-12-20

SAN FRANCISCO, CA—December 20, 2012—Scientists at the Gladstone Institutes have mapped the molecular mechanism by which a virus known as cytomegalovirus (CMV) so successfully infects its hosts. This discovery paves the way for new research avenues aimed at fighting this and other seemingly benign viruses that can turn deadly.

Not all viruses are created equal. Some ravage the body quickly, while others—after an initial infection—lie dormant for decades. CMV is one of the eight types of human herpes viruses, a family of viruses that also include Epstein-Barr virus (which ...

Dragonflies have human-like 'selective attention'

2012-12-20

In a discovery that may prove important for cognitive science, our understanding of nature and applications for robot vision, researchers at the University of Adelaide have found evidence that the dragonfly is capable of higher-level thought processes when hunting its prey.

The discovery, to be published online today in the journal Current Biology, is the first evidence that an invertebrate animal has brain cells for selective attention, which has so far only been demonstrated in primates.

Dr Steven Wiederman and Associate Professor David O'Carroll from the University ...

Origin of life emerged from cell membrane bioenergetics

2012-12-20

A coherent pathway which starts from no more than rocks, water and carbon dioxide and leads to the emergence of the strange bio-energetic properties of living cells, has been traced for the first time in a major hypothesis paper in Cell this week.

At the origin of life the first protocells must have needed a vast amount of energy to drive their metabolism and replication, as enzymes that catalyse very specific reactions were yet to evolve. Most energy flux must have simply dissipated without use.

So where did it all that energy come from on the early Earth, and how ...

A urine test for a rare and elusive disease

2012-12-20

Boston, Mass.—A set of proteins detected in urine by researchers at Boston Children's Hospital may prove to be the first biomarkers for Kawasaki disease, an uncommon but increasingly prevalent disease which causes inflammation of blood vessels that can lead to enlarged coronary arteries and even heart attacks in some children. If validated in more patients with Kawasaki disease, the markers could make the disease easier to diagnose and give doctors an opportunity to start treatment earlier.

The discovery was reported online by a team led by members of the Proteomics Center ...

First ever 'atlas' of T cells in human body

2012-12-20

New York, NY (December 20, 2012) — By analyzing tissues harvested from organ donors, Columbia University Medical Center (CUMC) researchers have created the first ever "atlas" of

immune cells in the human body. Their results provide a unique view of the distribution and function of T lymphocytes in healthy individuals. In addition, the findings represent a major step toward development of new strategies for creating vaccines and immunotherapies. The study was published today in the online edition of the journal Immunity.

T cells, a type of white blood cell, play a major ...

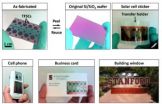

Peel-and-Stick solar panels from Stanford engineering

2012-12-20

For all their promise, solar cells have frustrated scientists in one crucial regard – most are rigid. They must be deployed in stiff, often heavy, fixed panels, limiting their applications. So researchers have been trying to get photovoltaics to loosen up. The ideal: flexible, decal-like solar panels that can be peeled off like band-aids and stuck to virtually any surface, from papers to window panes.

Now the ideal is real. Stanford researchers have succeeded in developing the world's first peel-and-stick thin-film solar cells. The breakthrough is described in a ...

Cellphone, GPS data suggest new strategy for alleviating traffic tie-ups

2012-12-20

Asking all commuters to cut back on rush-hour driving reduces traffic congestion somewhat, but asking specific groups of drivers to stay off the road may work even better.

The conclusion comes from a new analysis by engineers from the Massachusetts Institute of Technology and the University of California, Berkeley, that was made possible by their ability to track traffic using commuters' cellphone and GPS signals.

This is the first large-scale traffic study to track travel using anonymous cellphone data rather than survey data or information obtained from U.S. Census ...

Research pinpoints key gene for regenerating cells after heart attack

2012-12-20

DALLAS – Dec. 20, 2012 – UT Southwestern Medical Center researchers have pinpointed a molecular mechanism needed to unleash the heart's ability to regenerate, a critical step toward developing eventual therapies for damage suffered following a heart attack.

Cardiologists and molecular biologists at UT Southwestern, teaming up to study in mice how heart tissue regenerates, found that microRNAs – tiny strands that regulate gene expression – contribute to the heart's ability to regenerate up to one week after birth. Soon thereafter the heart loses the ability to regenerate. ...