(Press-News.org) A simple, precise and inexpensive method for cutting DNA to insert genes into human cells could transform genetic medicine, making routine what now are expensive, complicated and rare procedures for replacing defective genes in order to fix genetic disease or even cure AIDS.

Discovered last year by Jennifer Doudna and Martin Jinek of the Howard Hughes Medical Institute and University of California, Berkeley, and Emmanuelle Charpentier of the Laboratory for Molecular Infection Medicine-Sweden, the technique was labeled a "tour de force" in a 2012 review in the journal Nature Biotechnology.

That review was based solely on the team's June 28, 2012, Science paper, in which the researchers described a new method of precisely targeting and cutting DNA in bacteria.

Two new papers published last week in the journal Science Express demonstrate that the technique also works in human cells. A paper by Doudna and her team reporting similarly successful results in human cells has been accepted for publication by the new open-access journal eLife.

"The ability to modify specific elements of an organism's genes has been essential to advance our understanding of biology, including human health," said Doudna, a professor of molecular and cell biology and of chemistry and a Howard Hughes Medical Institute Investigator at UC Berkeley. "However, the techniques for making these modifications in animals and humans have been a huge bottleneck in both research and the development of human therapeutics.

"This is going to remove a major bottleneck in the field, because it means that essentially anybody can use this kind of genome editing or reprogramming to introduce genetic changes into mammalian or, quite likely, other eukaryotic systems."

"I think this is going to be a real hit," said George Church, professor of genetics at Harvard Medical School and principal author of one of the Science Express papers. "There are going to be a lot of people practicing this method because it is easier and about 100 times more compact than other techniques."

"Based on the feedback we've received, it's possible that this technique will completely revolutionize genome engineering in animals and plants," said Doudna, who also holds an appointment at Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory. "It's easy to program and could potentially be as powerful as the Polymerase Chain Reaction (PCR)."

The latter technique made it easy to generate millions of copies of small pieces of DNA and permanently altered biological research and medical genetics.

Cruise missiles

Two developments – zinc-finger nucleases and TALEN (Transcription Activator-Like Effector Nucleases) proteins – have gotten a lot of attention recently, including being together named one of the top 10 scientific breakthroughs of 2012 by Science magazine. The magazine labeled them "cruise missiles" because both techniques allow researchers to home in on a particular part of a genome and snip the double-stranded DNA there and there only.

Researchers can use these methods to make two precise cuts to remove a piece of DNA and, if an alternative piece of DNA is supplied, the cell will plug it into the cut instead. In this way, doctors can excise a defective or mutated gene and replace it with a normal copy. Sangamo Biosciences, a clinical stage biospharmaceutical company, has already shown that replacing one specific gene in a person infected with HIV can make him or her resistant to AIDS.

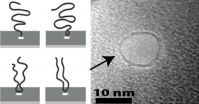

Both the zinc finger and TALEN techniques require synthesizing a large new gene encoding a specific protein for each new site in the DNA that is to be changed. By contrast, the new technique uses a single protein that requires only a short RNA molecule to program it for site-specific DNA recognition, Doudna said.

In the new Science Express paper, Church compared the new technique, which involves an enzyme called Cas9, with the TALEN method for inserting a gene into a mammalian cell and found it five times more efficient.

"It (the Cas9-RNA complex) is easier to make than TALEN proteins, and it's smaller," making it easier to slip into cells and even to program hundreds of snips simultaneously, he said. The complex also has lower toxicity in mammalian cells than other techniques, he added.

"It's too early to declare total victory" over TALENs and zinc-fingers, Church said, "but it looks promising."

Based on the immune systems of bacteria

Doudna discovered the Cas9 enzyme while working on the immune system of bacteria that have evolved enzymes that cut DNA to defend themselves against viruses. These bacteria cut up viral DNA and stick pieces of it into their own DNA, from which they make RNA that binds and inactivates the viruses.

UC Berkeley professor of earth and planetary science Jill Banfield brought this unusual viral immune system to Doudna's attention a few years ago, and Doudna became intrigued. Her research focuses on how cells use RNA (ribonucleic acids), which are essentially the working copies that cells make of the DNA in their genes.

Doudna and her team worked out the details of how the enzyme-RNA complex cuts DNA: the Cas9 protein assembles with two short lengths of RNA, and together the complex binds a very specific area of DNA determined by the RNA sequence. The scientists then simplified the system to work with only one piece of RNA and showed in the earlier Science paper that they could target and snip specific areas of bacterial DNA.

"The beauty of this compared to any of the other systems that have come along over the past few decades for doing genome engineering is that it uses a single enzyme," Doudna said. "The enzyme doesn't have to change for every site that you want to target – you simply have to reprogram it with a different RNA transcript, which is easy to design and implement."

The three new papers show this bacterial system works beautifully in human cells as well as in bacteria.

"Out of this somewhat obscure bacterial immune system comes a technology that has the potential to really transform the way that we work on and manipulate mammalian cells and other types of animal and plant cells," Doudna said. "This is a poster child for the role of basic science in making fundamental discoveries that affect human health."

INFORMATION:

Doudna's coauthors include Jinek and Alexandra East, Aaron Cheng and Enbo Ma of UC Berkeley's Department of Molecular and Cell Biology.

Doudna's work was sponsored by the Howard Hughes Medical Institute.

Cheap and easy technique to snip DNA could revolutionize gene therapy

Bacterial enzyme binds with RNA to home in on genes and cut double-stranded DNA

2013-01-08

ELSE PRESS RELEASES FROM THIS DATE:

Space-simulation study reveals sodium rhythms in the body

2013-01-08

Maintaining the right sodium levels in the body is crucial for controlling blood pressure and ensuring proper muscle function. Conventional wisdom has suggested that constant sodium levels are achieved through the balance of sodium intake and urinary excretion, but a new study in humans published by Cell Press on January 9th in the journal Cell Metabolism reveals that sodium levels actually fluctuate rhythmically over the course of weeks, independent of salt intake. This one-of-a-kind study, which examined cosmonauts participating in space-flight simulation studies, challenges ...

Most physicians do not meet Medicare quality reporting requirements

2013-01-08

Washington, DC – A new Harvey L. Neiman Health Policy Institute study shows that fewer than one-in-five healthcare providers meet Medicare Physician Quality Reporting System (PQRS) requirements. Those that meet PQRS thresholds now receive a .5 percent Medicare bonus payment. In 2015, bonuses will be replaced by penalties for providers who do not meet PQRS requirements. As it stands, more than 80 percent of providers nationwide would face these penalties.

Researchers analyzed 2007-2010 PQRS program data and found that nearly 24 percent of eligible radiologists qualified ...

Genes and obesity: Fast food isn't only culprit in expanding waistlines -- DNA is also to blame

2013-01-08

Researchers at UCLA say it's not just what you eat that makes those pants tighter — it's also genetics. In a new study, scientists discovered that body-fat responses to a typical fast-food diet are determined in large part by genetic factors, and they have identified several genes they say may control those responses.

The study is the first of its kind to detail metabolic responses to a high-fat, high-sugar diet in a large and diverse mouse population under defined environmental conditions, modeling closely what is likely to occur in human populations. The researchers ...

Brief class on easy-to-miss precancerous polyps ups detection, Mayo study shows

2013-01-08

JACKSONVILLE, Fla. — Most people know a colonoscopy requires some preparation by the patient. Now, a Mayo Clinic physician suggests an additional step to lower the risk of colorectal cancer: Ask for your doctor's success rate detecting easy-to-miss polyps called adenomas.

The measure of success is called the adenoma detection rate, or ADR, and has been linked to a reduced risk of developing a new cancer after the colonoscopy. The current recommended national benchmark is at least 20 percent, which means that an endoscopist should be able to detect adenomas in at least ...

New research may explain why obese people have higher rates of asthma

2013-01-08

New York, NY — A new study led by Columbia University Medical Center (CUMC) researchers has found that leptin, a hormone that plays a key role in energy metabolism, fertility, and bone mass, also regulates airway diameter. The findings could explain why obese people are prone to asthma and suggest that body weight–associated asthma may be relieved with medications that inhibit signaling through the parasympathetic nervous system, which mediates leptin function. The study, conducted in mice, was published in the online edition of the journal Cell Metabolism.

"Our study ...

Simulated Mars mission reveals body's sodium rhythms

2013-01-08

Clinical pharmacologist Jens Titze, M.D., knew he had a one-of-a-kind scientific opportunity: the Russians were going to simulate a flight to Mars, and he was invited to study the participating cosmonauts.

Titze, now an associate professor of Medicine at Vanderbilt University, wanted to explore long-term sodium balance in humans. He didn't believe the textbook view – that the salt we eat is rapidly excreted in urine to maintain relatively constant body sodium levels. The "Mars500" simulation gave him the chance to keep salt intake constant and monitor urine sodium levels ...

Researchers identify new target for common heart condition

2013-01-08

Researchers have found new evidence that metabolic stress can increase the onset of atrial arrhythmias, such as atrial fibrillation (AF), a common heart condition that causes an irregular and often abnormally fast heart rate. The findings may pave the way for the development of new therapies for the condition which can be expected to affect almost one in four of the UK population at some point in their lifetime.

The British Heart Foundation (BHF) study, led by University of Bristol scientists and published in Circulation: Arrhythmia and Electrophysiology, found that metabolic ...

DNA prefers to dive head first into nanopores

2013-01-08

PROVIDENCE, R.I. [Brown University] — If you want to understand a novel, it helps to start from the beginning rather than trying to pick up the plot from somewhere in the middle. The same goes for analyzing a strand of DNA. The best way to make sense of it is to look at it head to tail.

Luckily, according to a new study by physicists at Brown University, DNA molecules have a convenient tendency to cooperate.

The research, published in the journal Physical Review Letters, looks at the dynamics of how DNA molecules are captured by solid-state nanopores, tiny holes that ...

Scientists mimic fireflies to make brighter LEDs

2013-01-08

The nighttime twinkling of fireflies has inspired scientists to modify a light-emitting diode (LED) so it is more than one and a half times as efficient as the original. Researchers from Belgium, France, and Canada studied the internal structure of firefly lanterns, the organs on the bioluminescent insects' abdomens that flash to attract mates. The scientists identified an unexpected pattern of jagged scales that enhanced the lanterns' glow, and applied that knowledge to LED design to create an LED overlayer that mimicked the natural structure. The overlayer, which increased ...

Unlike we thought for 100 years: Molds are able to reproduce sexually

2013-01-08

For over 100 years, it was assumed that the penicillin-producing mould fungus Penicillium chrysogenum only reproduced asexually through spores. An international research team led by Prof. Dr. Ulrich Kück and Julia Böhm from the Chair of General and Molecular Botany at the Ruhr-Universität has now shown for the first time that the fungus also has a sexual cycle, i.e. two "genders". Through sexual reproduction of P. chrysogenum, the researchers generated fungal strains with new biotechnologically relevant properties - such as high penicillin production without the contaminating ...

LAST 30 PRESS RELEASES:

Low-temperature-activated deployment of smart 4D-printed vascular stents

Clinical relevance of brain functional connectome uniqueness in major depressive disorder

For dementia patients, easy access to experts may help the most

YouTubers love wildlife, but commenters aren't calling for conservation action

New study: Immune cells linked to Epstein-Barr virus may play a role in MS

AI tool predicts brain age, cancer survival, and other disease signals from unlabeled brain MRIs

Peak mental sharpness could be like getting in an extra 40 minutes of work per day, study finds

No association between COVID-vaccine and decrease in childbirth

AI enabled stethoscope demonstrated to be twice as efficient at detecting valvular heart disease in the clinic

Development by Graz University of Technology to reduce disruptions in the railway network

Large study shows scaling startups risk increasing gender gaps

Scientists find a black hole spewing more energy than the Death Star

A rapid evolutionary process provides Sudanese Copts with resistance to malaria

Humidity-resistant hydrogen sensor can improve safety in large-scale clean energy

Breathing in the past: How museums can use biomolecular archaeology to bring ancient scents to life

Dementia research must include voices of those with lived experience

Natto your average food

Family dinners may reduce substance-use risk for many adolescents

Kumamoto University Professor Kazuya Yamagata receives 2025 Erwin von Bälz Prize (Second Prize)

Sustainable electrosynthesis of ethylamine at an industrial scale

A mint idea becomes a game changer for medical devices

Innovation at a crossroads: Virginia Tech scientist calls for balance between research integrity and commercialization

Tropical peatlands are a major source of greenhouse gas emissions

From cytoplasm to nucleus: A new workflow to improve gene therapy odds

Three Illinois Tech engineering professors named IEEE fellows

Five mutational “fingerprints” could help predict how visible tumours are to the immune system

Rates of autism in girls and boys may be more equal than previously thought

Testing menstrual blood for HPV could be “robust alternative” to cervical screening

Are returning Pumas putting Patagonian Penguins at risk? New study reveals the likelihood

Exposure to burn injuries played key role in shaping human evolution, study suggests

[Press-News.org] Cheap and easy technique to snip DNA could revolutionize gene therapyBacterial enzyme binds with RNA to home in on genes and cut double-stranded DNA