(Press-News.org) Nature's ability to create iridescent flowers has been recreated by mathematicians at The University of Nottingham. The team of researchers have collaborated with experimentalists at the University of Cambridge to create a mathematical model of a plant's petals to help us learn more about iridescence in flowering plants and the role it may play in attracting pollinators.

An iridescent surface appears to change colour as you alter the angle you view it from. It is found in the animal kingdom in insects, inside sea shells and in feathers, and is also seen in some plants. Iridescence in flowers may act as a signal to pollinators such as bumble-bees, which are crucial to crop production.

Understanding how petals produce iridescence to attract pollinators is a major goal in plant biology. An estimated 35 per cent of global crop production depends on petal-mediated animal pollination but a decrease in pollinator numbers across the world has started to limit the odds of pollination and reduce crop production rates.

Flowers and the animals that pollinate plants interact at the petal surface. The surfaces of many petals have regular patterns, produced from folds of the waterproof cuticle layer that covers all plant surfaces. These patterns can interfere with light to produce strong optical effects including iridescent colours, and might also influence animal grip.

Iridescence in plants is produced by nanoscale ridges on the top of the cells in the petal's epidermal surface. These tiny ridges produce structures called diffraction gratings. The particular shape and spacing of these ridges and the shape of the cells sculpt the outermost layer of the petal giving it a unique physical, mechanical or optical property. These properties interfere with different wavelengths of light creating the colour variation when it is seen at different angles. Pollinators, such as bumblebees, can detect the iridescent signal produced by petal nanoridges and can learn to use this signal as a cue to identify rewarding flowers.

The research has been published in the Journal of The Royal Society Interface. Rea Antoniou Kourounioti, a PhD student in the School of Biosciences, said: "We provide a first analysis of how petal surface patterns might be produced. Our team of researchers combined experimental data with mathematical modelling to develop a biomechanical model of the outer layers of a petal or leaf. We used this to demonstrate that mechanical buckling of the outermost, waxy cuticle layer, can create the ridge patterns observed in nature on petals and leaves. Learning more about how iridescence is produced is important for pollination of crops and also for other types of patterning in biology."

###

The research was undertaken by The University of Nottingham, University of Cambridge, University of Manchester and Biotalentum Ltd, and has been published in the Journal of the Royal Society Interface. The study was initiated by the Mathematics in the Plant Sciences Study Group, an annual UK-based workshop organised by The University of Nottingham's Centre for Plant Integrative Biology, which kick-starts collaborations between plant scientists and mathematicians. END

How does your garden glow?

2013-01-14

ELSE PRESS RELEASES FROM THIS DATE:

How do happiness and sadness circuits contribute to bipolar disorder?

2013-01-14

Philadelphia, PA, January 14, 2013 – Bipolar disorder is a severe mood disorder characterized by unpredictable and dramatic mood swings between the highs of mania and lows of depression. These mood episodes occur among periods of 'normal mood', termed euthymia.

Prior research has clearly shown that brain emotion circuitry is dysregulated in individuals diagnosed with bipolar disorder. It is thought that these disturbances impair one's ability to control emotion and contribute to mood episodes.

Continuing this line of research, the January 15th issue of Biological Psychiatry ...

Global warming has increased monthly heat records by a factor of 5

2013-01-14

Monthly temperature extremes have become much more frequent, as measurements from around the world indicate. On average, there are now five times as many record-breaking hot months worldwide than could be expected without long-term global warming, shows a study now published in Climatic Change. In parts of Europe, Africa and southern Asia the number of monthly records has increased even by a factor of ten. 80 percent of observed monthly records would not have occurred without human influence on climate, concludes the authors-team of the Potsdam Institute for Climate Impact ...

Protein identified that can disrupt embryonic brain development and neuron migration

2013-01-14

Interneurons – nerve cells that function as 'dimmers' – play an important role in the brain. Their formation and migration to the cerebral cortex during the embryonic stage of development is crucial to normal brain functioning. Abnormal interneuron development and migration can eventually lead to a range of disorders and diseases, from epilepsy to Alzheimer's. New research by Dr. Eve Seuntjens and Dr. Veronique van den Berghe of the Department of Development and Regeneration (Danny Huylebroeck laboratory, Faculty of Medicine) at KU Leuven (University of Leuven) has identified ...

Research makes connetion between tubal ligation and increase in cervical cancer rates

2013-01-14

Women who have a tubal ligation – the surgical tying or severing of fallopian tubes to prohibit pregnancy – have less frequent Pap smears, which puts them at an increased risk for cervical cancer, according to research recently released by a team that included Cara A. Mathews, MD, a gynecologic oncologist at the Program in Women's Oncology at Women & Infants Hospital of Rhode Island.

The findings were part of the National Cancer Institute-funded study "Study to Understand Cervical Cancer Endpoints and Determinants" being conducted when Dr. Mathews was a fellow at the ...

Liver controls wasting in cancer

2013-01-14

Cachexia or wasting is a condition affecting up to 70 percent of cancer patients, depending on the type of cancer. It is characterized by a dramatic loss of body weight that is independent of food intake. Cachexia is seen particularly often and most pronounced in patients suffering from cancers of the digestive tract and the lungs. They may lose up to 80 percent of body fat and skeletal muscle. Muscle loss leads to weakness and immobility of patients and poorer response to treatment. An estimated 20 percent of cancer deaths are considered to be a direct consequence of cachexia, ...

Dynamic, dark energy in an accelerating universe

2013-01-14

This press release is available in Spanish.

It was cosmology that drew Irene Sendra from Valencia to the Basque Country. Cosmology alsogave her the chance to collaborate with one of the winners of the 2011 Nobel Prize for Physics on one of the darkest areas of the universe. And dark matter and dark energy, well-known precisely because so little is known about them, are in fact the object of the study bySendra, a researcher in the Department of Theoretical Physics and History of Science of the UPV/EHU's Faculty of Science and Technology.

"Observations tell us that ...

NRL designs multi-junction solar cell to break efficiency barrier

2013-01-14

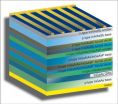

WASHINGTON -- U.S. Naval Research Laboratory scientists in the Electronics Technology and Science Division, in collaboration with the Imperial College London and MicroLink Devices, Inc., Niles, Ill., have proposed a novel triple-junction solar cell with the potential to break the 50 percent conversion efficiency barrier, which is the current goal in multi-junction photovoltaic development.

"This research has produced a novel, realistically achievable, lattice-matched, multi-junction solar cell design with the potential to break the 50 percent power conversion efficiency ...

Using lysine estimates to detect heat damage in DDGS

2013-01-14

URBANA – Distillers dried grains with solubles (DDGS) are a good source of energy and protein in swine diets. However, they can be damaged by excessive heat during processing, compromising their nutritional value. University of Illinois researchers have found that it is possible to assess heat damage by predicting the digestibility of lysine in DDGS.

Excessive heat causes some of the lysine in DDGS to bond with sugars and form Amadori compounds. The lysine bound in these compounds is called unreactive lysine; pigs cannot digest it. Lysine that is not bound is referred ...

Amino acid studies may aid battle against citrus greening disease

2013-01-14

This press release is available in Spanish.Amino acids in orange juice might reveal secrets to the successful attack strategy of the plant pathogen that causes citrus greening disease, also known as Huanglongbing or HLB. Studies of these amino acids by U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA) chemist Andrew P. Breksa III and University of California-Davis professor Carolyn M. Slupsky may pave the way to a safe, effective, environmentally friendly approach to undermine Candidatus Liberibacter asiaticus, the microbial culprit behind HLB.

The scientists used nuclear magnetic ...

ASH international clinical collaboration replicates high cure rate of APL in developing countries

2013-01-14

(WASHINGTON) – Data published online today in Blood, the Journal of the American Society of Hematology (ASH) describe the work of an ASH international clinical network collaborative focused on modernizing treatment protocols for patients in the developing world with acute promyeloctyic leukemia (APL) that has drastically improved cure rates in patients in Central and South America, achieving comparable outcomes to those observed in patients in the United States and in Europe.

APL is a rare, aggressive cancer of the blood and bone marrow that can be fatal in a matter ...