(Press-News.org) Concerns that many animals are becoming extinct, before scientists even have time to identify them, are greatly overstated according Griffith University researcher, Professor Nigel Stork.

Professor Stork has taken part in an international study, the findings of which have been detailed in "Can we name Earth's species before they go extinct?" published in the journal Science.

Deputy Head of the Griffith School of Environment, Professor Stork said a number of misconceptions have fuelled these fears, and there is no evidence that extinction rates are as high as some have feared.

"Surprisingly, few species have gone extinct, to our knowledge. Of course, there will have been some species which have disappeared without being recorded, but not many we think," Professor Stork said.

Professor Stork said part of the problem is that there is an inflated sense of just how many animals exist and therefore how big the task to record them.

"Modern estimates of the number of eukaryotic species have ranged up to 100 million, but we have estimated that there are around 5 million species on the planet (plus or minus 3 million)."

And there are more scientists than ever working on the task. This contrary to a common belief that we are losing taxonomists, the scientists who identify species.

"While this is the case in the developed world where governments are reducing funding, in developing nations the number of taxonomists is actually on the rise.

"World-wide there are now two to three times as many taxonomist describing species as there were 20 years ago."

Even so, Professor Stork says the scale of the global taxonomic challenge is not to be underestimated.

"The task of identifying and naming all existing species of animals is still daunting, as there is much work to be done."

Other good news for the preservation of species is that conservation efforts in the past few years have done a good job in protecting some key areas of rich biodiversity.

But the reprieve may be short-lived.

"Climate change will dramatically change species survival rates, particularly when you factor in other drivers such as overhunting and habitat loss," Professor Stork said.

"At this stage we have no way of knowing by how much extinction rates may escalate.

"But once global warming exceeds the 2 degree barrier, we can expect to see the scale of loss many people already believe is happening. Higher temperature rises coupled with other environmental impacts will lead to mass extinctions"

INFORMATION:

Media contact: Helen Wright: 0478 406 565, helen.wright@griffith.edu.au

Extinction rates not as bad as feared ... for now

Griffith University scientists challenge common belief

2013-01-25

ELSE PRESS RELEASES FROM THIS DATE:

Organizing human specimen collections: Getting the best out of biobanks

2013-01-25

The diversity of biobanks, collections of human specimens from a variety of sources, raises questions about the best way to manage and govern them, finds a study published in BioMed Central's open access journal Genome Medicine. The research highlights difficulties in standardizing these collections and how to make these samples available for research.

Biobanks have been around for decades, storing hundreds of millions of human specimens. But there has been a dramatic increase in the number of biobanks in the last ten years, since the human genome sequencing project. ...

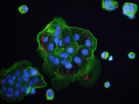

Immune cell suicide alarm helps destroy escaping bacteria

2013-01-25

CHAPEL HILL, N.C. – Cells in the immune system called macrophages normally engulf and kill intruding bacteria, holding them inside a membrane-bound bag called a vacuole, where they kill and digest them.

Some bacteria thwart this effort by ripping the bag open and then escaping into the macrophage's nutrient-rich cytosol compartment, where they divide and could eventually go on to invade other cells.

But research from the University of North Carolina School of Medicine shows that macrophages have a suicide alarm system, a signaling pathway to detect this escape into ...

Out-of-pocket costs for breast cancer probably manageable for most Canadian women

2013-01-25

Out-of-pocket costs resulting from breast cancer care in the year following diagnosis are likely manageable for most women, but some women are at a higher risk of experiencing the financial burden that comes from those costs in Canadian breast cancer patients, according to a study published January 24 in the Journal of the National Cancer Institute.

While extensive information about the level of out-of-pocket costs after early breast cancer diagnosis has been unavailable until now, the costs resulting from the disease and the effects the costs have on family financial ...

Fruit and vegetable intake is associated with lower risk of ER- breast cancer

2013-01-25

There is no association between total fruit and vegetable intake and risk of overall breast cancer, but vegetable consumption is associated with a lower risk of estrogen receptor-negative (ER-) breast cancer, according to a study published January 24 in the Journal of the National Cancer Institute.

The intake of fruits and vegetables has been hypothesized to lower breast cancer risk, however the existing evidence is inconclusive. There are many subtypes of breast cancer including ER- and ER positive (ER+) tumors and each may have distinct etiologies. Since ER- tumors, ...

Spotting fetal growth problems early could cut UK stillbirths by 600 a year

2013-01-25

The authors say spotting it early could substantially reduce the risk, and this needs to become a cornerstone of safety and effectiveness in antenatal care.

Stillbirth rates in the United Kingdom are among the highest in developed countries. They have often been considered unexplained and unavoidable, and their rates have changed little over the last two decades.

Recently, doctors have found that many stillborn babies fail to reach their growth potential, prompting a renewed focus on what causes fetal growth restriction. So a team of researchers at the West Midlands ...

Scientists discover how epigenetic information could be inherited

2013-01-25

New research reveals a potential way for how parents' experiences could be passed to their offspring's genes. The research was published today, 25 January, in the journal Science.

Epigenetics is a system that turns our genes on and off. The process works by chemical tags, known as epigenetic marks, attaching to DNA and telling a cell to either use or ignore a particular gene.

The most common epigenetic mark is a methyl group. When these groups fasten to DNA through a process called methylation they block the attachment of proteins which normally turn the genes on. ...

Researchers discover new mutations driving malignant melanoma

2013-01-25

BOSTON—Two new mutations that collectively occur in 71 percent of malignant melanoma tumors have been discovered in what scientists call the "dark matter" of the cancer genome, where cancer-related mutations haven't been previously found.

Reporting their findings in the Jan. 24 issue of Science Express, the researchers from Dana-Farber Cancer Institute and the Broad Institute said the highly "recurrent" mutations – occurring in the tumors of many people – may be the most common mutations in melanoma cells found to date.

The researchers said these cancer-associated ...

Red explosions: The secret life of binary stars is revealed

2013-01-25

(Edmonton) A University of Alberta professor has revealed the workings of a celestial event involving binary stars that results in an explosion so powerful it ranks close to Supernovae in luminosity.

Astrophysicists have long debated about what happens when binary stars, two stars that orbit one another, come together in a common envelope.

When this dramatic cannibalizing event ends there are two possible outcomes; the two stars merge into a single star or an initial binary transforms in an exotic short-period one.

The event is believed to take anywhere from a dozen ...

Gene sequencing project mines data once considered 'junk' for clues about cancer

2013-01-25

(MEMPHIS, Tenn. – January 24, 2013) Genome sequencing data once regarded as junk is now being used to gain important clues to help understand disease. The latest example comes from the St. Jude Children's Research Hospital – Washington University Pediatric Cancer Genome Project, where scientists have developed an approach to mine the repetitive segments of DNA at the ends of chromosomes for insights into cancer.

These segments, known as telomeres, had previously been ignored in next-generation sequencing efforts. That is because their repetitive nature meant that the ...

Newly discovered 'scarecrow' gene might trigger big boost in food production

2013-01-25

ITHACA, N.Y. – With projections of 9.5 billion people by 2050, humanity faces the challenge of feeding modern diets to additional mouths while using the same amounts of water, fertilizer and arable land as today.

Cornell University researchers have taken a leap toward meeting those needs by discovering a gene that could lead to new varieties of staple crops with 50 percent higher yields.

The gene, called Scarecrow, is the first discovered to control a special leaf structure, known as Kranz anatomy, which leads to more efficient photosynthesis. Plants photosynthesize ...

LAST 30 PRESS RELEASES:

Scientists reveal our best- and worst-case scenarios for a warming Antarctica

Cleaner fish show intelligence typical of mammals

AABNet and partners launch landmark guide on the conservation of African livestock genetic resources and sustainable breeding strategies

Produce hydrogen and oxygen simultaneously from a single atom! Achieve carbon neutrality with an 'All-in-one' single-atom water electrolysis catalyst

Sleep loss linked to higher atrial fibrillation risk in working-age adults

Visible light-driven deracemization of α-aryl ketones synergistically catalyzed by thiophenols and chiral phosphoric acid

Most AI bots lack basic safety disclosures, study finds

How competitive gaming on discord fosters social connections

CU Anschutz School of Medicine receives best ranking in NIH funding in 20 years

Mayo Clinic opens patient information office in Cayman Islands

Phonon lasers unlock ultrabroadband acoustic frequency combs

Babies with an increased likelihood of autism may struggle to settle into deep, restorative sleep, according to a new study from the University of East Anglia.

National Reactor Innovation Center opens Molten Salt Thermophysical Examination Capability at INL

International Progressive MS Alliance awards €6.9 million to three studies researching therapies to address common symptoms of progressive MS

Can your soil’s color predict its health?

Biochar nanomaterials could transform medicine, energy, and climate solutions

Turning waste into power: scientists convert discarded phone batteries and industrial lignin into high-performance sodium battery materials

PhD student maps mysterious upper atmosphere of Uranus for the first time

Idaho National Laboratory to accelerate nuclear energy deployment with NVIDIA AI through the Genesis Mission

Blood test could help guide treatment decisions in germ cell tumors

New ‘scimitar-crested’ Spinosaurus species discovered in the central Sahara

“Cyborg” pancreatic organoids can monitor the maturation of islet cells

Technique to extract concepts from AI models can help steer and monitor model outputs

Study clarifies the cancer genome in domestic cats

Crested Spinosaurus fossil was aquatic, but lived 1,000 kilometers from the Tethys Sea

MULTI-evolve: Rapid evolution of complex multi-mutant proteins

A new method to steer AI output uncovers vulnerabilities and potential improvements

Why some objects in space look like snowmen

Flickering glacial climate may have shaped early human evolution

First AHA/ACC acute pulmonary embolism guideline: prompt diagnosis and treatment are key

[Press-News.org] Extinction rates not as bad as feared ... for nowGriffith University scientists challenge common belief