(Press-News.org) Viruses similar to those that cause AIDS in humans were present in non-human primates in Africa at least 5 million years ago and perhaps up to 12 million years ago, according to study published January 24 in the Open Access journal PLOS Pathogens by scientists at Fred Hutchinson Cancer Research Center. Until now, researchers have hypothesized that such viruses originated much more recently.

HIV-1, the virus responsible for AIDS, infiltrated the human population in the early 20th century following multiple transmissions of a similar chimpanzee virus known as SIVcpz. Previous work to determine the age of HIV-like viruses, called lentiviruses, by comparing their genetic blueprints has calculated their origin to be tens of thousands of years ago.

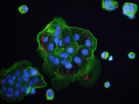

However, other researchers have suspected this time frame to be much too recent. Michael Emerman, Ph.D., a virologist and member of the Human Biology Division at Fred Hutchinson Cancer Research Center, and Alex Compton, a graduate student in the Emerman Lab, describe the use of a technique to estimate the extent to which primates and lentiviruses have coexisted by tracking the changes in a host immunity gene called APOBEC3G that were induced by ancient viral challenges.

They report that this host immunity factor is evolving in tandem with a viral gene that defends the virus against APOBEC3G, which allowed them to determine the minimum age for the association between primates and lentiviruses to be around 5 or 6 million years ago, and possibly up to 12 million years ago.

These findings suggest that HIV-like infections in primates are much older than previously thought, and they have driven selective changes in antiviral genes that have incited an evolutionary arms race that continues to this day. The study also confirms that viruses similar to HIV that are present in various monkey species today are the descendants of ancient pathogens in primates that have shaped how the immune system fights infections.

"More than 40 non-human primate species in sub-Saharan Africa are infected with strains of HIV-related viruses," Emerman said. "Since some of these viruses may have the potential to infect humans as well, it is important to know their origins."

###

FINANCIAL DISCLOSURE: This work was supported by R01 A130937 (to ME) and an NSF Graduate Research Fellowship and NIH Training Grant in Viral Pathogenesis T32AI083203 (to AAC). The funders had no role in study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript.

COMPETING INTERESTS: The authors have declared that no competing interests exist.

PLEASE ADD THIS LINK TO THE PUBLISHED ARTICLE IN ONLINE VERSIONS OF YOUR REPORT:

http://dx.plos.org/10.1371/journal.ppat.1003135

(link will go live upon embargo lift)

CITATION: Compton AA, Emerman M (2013) Convergence and Divergence in the Evolution of the APOBEC3G-Vif Interaction Reveal Ancient Origins of Simian Immunodeficiency Viruses. PLoS Pathog 9(1): e1003135. doi:10.1371/journal.ppat.1003135

Institutional Contact:

Kristen Lidke Woodward

(206) 667-5095

kwoodwar@fhcrc.org

Disclaimer

This press release refers to an upcoming article in PLOS Pathogens. The release is provided by the article authors. Any opinions expressed in these releases or articles are the personal views of the journal staff and/or article contributors, and do not necessarily represent the views or policies of PLOS. PLOS expressly disclaims any and all warranties and liability in connection with the information found in the releases and articles and your use of such information.

Media Permissions

PLOS Journals publish under a Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits free reuse of all materials published with the article, so long as the work is cited (e.g., Kaltenbach LS et al. (2007) Huntingtin Interacting Proteins Are Genetic Modifiers of Neurodegeneration. PLoS Genet 3(5): e82. doi:10.1371/journal.pgen.0030082). No prior permission is required from the authors or publisher. For queries about the license, please contact the relative journal contact indicated here: http://www.plos.org/about/media-inquiries/.

About PLOS Pathogens

PLOS Pathogens publishes outstanding original articles that significantly advance the understanding of pathogens and how they interact with their host organisms. All works published in PLOS Pathogens are open access. Everything is immediately available subject only to the condition that the original authorship and source are properly attributed. Copyright is retained by the authors. The Public Library of Science uses the Creative Commons Attribution License.

About the Public Library of Science

The Public Library of Science (PLOS) is a non-profit organization of scientists and physicians committed to making the world's scientific and medical literature a freely available public resource. For more information, visit http://www.plos.org.

END

For the tiny Daubenton's bat, the attractions of family life seem to vary more with altitude than with the allure of the opposite sex.

For more than a decade, a team led by Professor John Altringham from the University of Leeds' School of Biology has studied a population of several hundred bats along a 50-km stretch of the River Wharfe. They monitored roosts in Ilkley and Addingham, upstream in the market town of Grassington and higher still in the villages of Kettlewell and Buckden.

The researchers found that all Daubenton's bats in nursery roosts in lowland areas ...

Concerns that many animals are becoming extinct, before scientists even have time to identify them, are greatly overstated according Griffith University researcher, Professor Nigel Stork.

Professor Stork has taken part in an international study, the findings of which have been detailed in "Can we name Earth's species before they go extinct?" published in the journal Science.

Deputy Head of the Griffith School of Environment, Professor Stork said a number of misconceptions have fuelled these fears, and there is no evidence that extinction rates are as high as some have ...

The diversity of biobanks, collections of human specimens from a variety of sources, raises questions about the best way to manage and govern them, finds a study published in BioMed Central's open access journal Genome Medicine. The research highlights difficulties in standardizing these collections and how to make these samples available for research.

Biobanks have been around for decades, storing hundreds of millions of human specimens. But there has been a dramatic increase in the number of biobanks in the last ten years, since the human genome sequencing project. ...

CHAPEL HILL, N.C. – Cells in the immune system called macrophages normally engulf and kill intruding bacteria, holding them inside a membrane-bound bag called a vacuole, where they kill and digest them.

Some bacteria thwart this effort by ripping the bag open and then escaping into the macrophage's nutrient-rich cytosol compartment, where they divide and could eventually go on to invade other cells.

But research from the University of North Carolina School of Medicine shows that macrophages have a suicide alarm system, a signaling pathway to detect this escape into ...

Out-of-pocket costs resulting from breast cancer care in the year following diagnosis are likely manageable for most women, but some women are at a higher risk of experiencing the financial burden that comes from those costs in Canadian breast cancer patients, according to a study published January 24 in the Journal of the National Cancer Institute.

While extensive information about the level of out-of-pocket costs after early breast cancer diagnosis has been unavailable until now, the costs resulting from the disease and the effects the costs have on family financial ...

There is no association between total fruit and vegetable intake and risk of overall breast cancer, but vegetable consumption is associated with a lower risk of estrogen receptor-negative (ER-) breast cancer, according to a study published January 24 in the Journal of the National Cancer Institute.

The intake of fruits and vegetables has been hypothesized to lower breast cancer risk, however the existing evidence is inconclusive. There are many subtypes of breast cancer including ER- and ER positive (ER+) tumors and each may have distinct etiologies. Since ER- tumors, ...

The authors say spotting it early could substantially reduce the risk, and this needs to become a cornerstone of safety and effectiveness in antenatal care.

Stillbirth rates in the United Kingdom are among the highest in developed countries. They have often been considered unexplained and unavoidable, and their rates have changed little over the last two decades.

Recently, doctors have found that many stillborn babies fail to reach their growth potential, prompting a renewed focus on what causes fetal growth restriction. So a team of researchers at the West Midlands ...

New research reveals a potential way for how parents' experiences could be passed to their offspring's genes. The research was published today, 25 January, in the journal Science.

Epigenetics is a system that turns our genes on and off. The process works by chemical tags, known as epigenetic marks, attaching to DNA and telling a cell to either use or ignore a particular gene.

The most common epigenetic mark is a methyl group. When these groups fasten to DNA through a process called methylation they block the attachment of proteins which normally turn the genes on. ...

BOSTON—Two new mutations that collectively occur in 71 percent of malignant melanoma tumors have been discovered in what scientists call the "dark matter" of the cancer genome, where cancer-related mutations haven't been previously found.

Reporting their findings in the Jan. 24 issue of Science Express, the researchers from Dana-Farber Cancer Institute and the Broad Institute said the highly "recurrent" mutations – occurring in the tumors of many people – may be the most common mutations in melanoma cells found to date.

The researchers said these cancer-associated ...

(Edmonton) A University of Alberta professor has revealed the workings of a celestial event involving binary stars that results in an explosion so powerful it ranks close to Supernovae in luminosity.

Astrophysicists have long debated about what happens when binary stars, two stars that orbit one another, come together in a common envelope.

When this dramatic cannibalizing event ends there are two possible outcomes; the two stars merge into a single star or an initial binary transforms in an exotic short-period one.

The event is believed to take anywhere from a dozen ...