(Press-News.org) Microscopic ocean algae called coccolithophores are providing clues about the impact of climate change both now and many millions of years ago. The study found that their response to environmental change varies between species, in terms of how quickly they grow.

Coccolithophores, a type of plankton, are not only widespread in the modern ocean but they are also prolific in the fossil record because their tiny calcium carbonate shells are preserved on the seafloor after death – the vast chalk cliffs of Dover, for example, are almost entirely made of fossilised coccolithophores.

The fate of coccolithophores under changing environmental conditions is of interest because of their important role in the marine ecosystem and carbon cycle. Because of their calcite shells, these organisms are potentially sensitive to ocean acidification, which occurs when rising atmospheric carbon dioxide (CO2) is absorbed by the ocean, increasing its acidity.

There are many different species of coccolithophore and in an article, published in Nature Geoscience this week, the scientists report that they responded in different ways to a rapid climate warming event that occurred 56 million years ago, the Palaeocene-Eocene Thermal Maximum (PETM).

The study, involving researchers from the University of Southampton, the National Oceanography Centre and University College London, found that the species Toweius pertusus continued to reproduce relatively quickly despite rapidly changing environmental conditions. This would have provided a competitive advantage and is perhaps why closely-related modern-day species considered to be its descendants, (such as Emiliana huxleyi) still thrive today.

In contrast, the species Coccolithus pelagicus grew more slowly during the period of greatest warmth and this inability to maintain high growth rates may explain why its descendants are less abundant and less widespread in the modern ocean.

"This work provides us with a whole new way of looking at living and fossil coccolithophores," said lead author Dr Samantha Gibbs, Senior Research Fellow at University of Southampton Ocean and Earth Science.

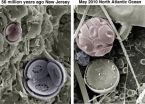

By comparing immaculately preserved and complete fossil cells with modern coccolithophore cells, the researchers could interpret how different species responded to the sudden increase in environmental change at the PETM, when atmospheric CO2 levels increased rapidly and the oceans became more acidic.

"We use knowledge of how coccolithophores build their calcite skeletons in the modern ocean to interpret how climate change 56 million years ago affected the growth of these microscopic plankton," said co-author Dr Alex Poulton, a Research Fellow at the National Oceanography Centre.

"This is a significant step forward and allows us to view fossils as cells rather than dead 'rocks'. Through this we can begin to understand the environmental controls on oceanic calcification, as well as the potential effects of climate change and ocean acidification."

INFORMATION:

The study was primarily supported by the UK Ocean Acidification Research Programme, which is jointly funded by the Natural Environment Research Council (NERC), the Department of Environment, Food and Rural Affairs (Defra) and the Department of Energy and Climate Change (DECC).

Notes to editors

Reference: Gibbs S.J., Poulton A.J., Bown P.R., Daniels C.J., Hopkins J. Young J.R., Jones H.L., Thiemann G.J., O'Dea S.A., Newsam C. (2013) Species-specific growth response of coccolithophores to Palaeocene–Eocene environmental change. Nature Geoscience doi: 10.1038/NGEO1719

The image shows fossil and modern coccolithophore cells of species Toweius pertusus and Coccolithus pelagicus. Courtesy of Paul Bown, University College London (UCL).

This collaborative study, which straddles modern and palaeo research, arose from linkages within the UK Ocean Acidification research programme (UKOA, co-funded by NERC, Defra and DECC). It was also supported by Royal Society and NERC Fellowships. UKOA aims to reduce uncertainties in the response of marine organisms, ecosystems and biogeochemistry to ocean acidification and other climate related stressors. Further information on UKOA can be found at: www.oceanacidification.org.uk

The study was led by the University of Southampton Ocean and Earth Science, based at the National Oceanography Centre, Southampton (NOCS). Co-authors were from NOCS itself and University College London (UCL).

The National Oceanography Centre (NOC) is the UK's leading institution for integrated coastal and deep ocean research. NOC operates the Royal Research Ships James Cook and Discovery on behalf of the Natural Environment Research Council, and develops technology for coastal and deep ocean research. Working with its partners NOC provides long-term marine science capability including: sustained ocean observing, mapping and surveying, data management and scientific advice.

NOC operates at two sites, Southampton and Liverpool, with the headquarters based in Southampton.

Among the resources that NOC provides on behalf of the UK are the British Oceanographic Data Centre (BODC), the Marine Autonomous and Robotic Systems (MARS) facility, the National Tide and Sea Level Facility (NTSLF), the Permanent Service for Mean Sea Level (PSMSL) and British Ocean Sediment Core Research Facility (BOSCORF).

The National Oceanography Centre is wholly owned by the Natural Environment Research Council (NERC).

For further information, please contact Catherine Beswick, Media and Communications Officer, National Oceanography Centre, +44 238 059 8490, catherine.beswick@noc.ac.uk.

Climate change clues from tiny marine algae -- ancient and modern

2013-02-04

ELSE PRESS RELEASES FROM THIS DATE:

The impressive aerial maneuvers of the pea aphid

2013-02-04

You might not think much about pea aphids, but it turns out they've got skills enough to get aerospace engineers excited. A report in the February 4th issue of Current Biology, a Cell Press publication, shows that the insects can free fall from the plants they feed on and—within a fraction of a second—land on their feet every time. Oftentimes, the falling aphids manage to cling to a lower part of the plant by their sticky feet on the way down, avoiding the dangerous ground altogether.

That's despite the fact that most aphids in a colony are wingless and have no special ...

Avoiding a cartography catastrophe

2013-02-04

KNOXVILLE, TN – Since the mid-nineteenth century, maps have helped elucidate the deadly mysteries of diseases like cholera and yellow fever. Yet today's global mapping of infectious diseases is considerably unreliable and may do little to inform the control of potential outbreaks, according to a new systematic mapping review of all clinically important infectious diseases known to humans.

Of the 355 infectious diseases assessed in the review, 174 showed a strong rationale for mapping and less than 5 percent of those have been mapped reliably. Unreliable mapping makes it ...

AB blood type strong risk factor for venous blood clots

2013-02-04

The non-O ABO blood type is the most important risk factor for venous thromboembolism (blood clots in veins), making up 20% of attributable risk for the condition, according to a new study in CMAJ (Canadian Medical Association Journal).

This finding has implications for genetic screening for thrombophilia, a genetic predisposition to abnormal blood clotting.

Danish researchers looked at data on 66 001 people who had been followed for 33 years from 1977 through 2010 to determine whether ABO blood type is associated with an increased risk of venous blood clots in the ...

Tuberculosis in Nunavut can be controlled

2013-02-04

A combined strategy is needed to combat tuberculosis in Nunavut where the rate is 66 times higher than in the general Canadian population, states a commentary in CMAJ (Canadian Medical Association Journal).

Nunavut, Canada's eastern territory in the north, has seen a dramatic increase in the disease since 1997. Previous efforts to eradicate the disease focused on early identification and treatment of people as well as treatment of latent cases. This intense approach helped decrease the number of cases, but was not continued.

"Intensive control activities should be expanded ...

Physicians' roles on the front line of climate change

2013-02-04

Physicians can and should help mitigate the negative health effects of climate change because they will be at the forefront of responding to the effects of global warming, argues an editorial in CMAJ (Canadian Medical Association Journal).

Doctors could use their political influence to lobby government on climate issues that are already affecting health and to become signatories to the Doha Declaration on Climate, Health and Wellbeing.

They can also act at a professional level, by leading health institutions to cut back on greenhouse gases and reduce clinical waste.

"The ...

JoVE expands scientific video publication into chemistry

2013-02-04

February 4, 2013

Cambridge, MA: On Monday, February 4, 2013, JoVE (Journal of Visualized Experiments) will launch the first scholarly scientific video publication for chemistry. Following its successful introduction of video publications for the biological and physical sciences, JoVE received numerous requests for a chemistry counterpart. In response, the journal is launching a new section, JoVE Chemistry, dedicated to visualized publication of experiments across different areas of chemistry research including organic chemistry, chemical biology, electrochemistry, and ...

Pitt researchers reveal mechanism to halt cancer cell growth, discover potential therapy

2013-02-04

PITTSBURGH, Feb. 4, 2013 – University of Pittsburgh Cancer Institute (UPCI) researchers have uncovered a technique to halt the growth of cancer cells, a discovery that led them to a potential new anti-cancer therapy.

When deprived of a key protein, some cancer cells are unable to properly divide, a finding described in the cover story of the February issue of the Journal of Cell Science. This research is supported in part by a grant from the National Institutes of Health.

"This is the first time anyone has explained how altering this protein at a key stage in cell ...

Men are from Mars Earth, women are from Venus Earth

2013-02-04

For decades, popular writers have entertained readers with the premise that men and women are so psychologically dissimilar they could hail from entirely different planets. But a new study shows that it's time for the Mars/Venus theories about the sexes to come back to Earth.

From empathy and sexuality to science inclination and extroversion, statistical analysis of 122 different characteristics involving 13,301 individuals shows that men and women, by and large, do not fall into different groups. In other words, no matter how strange and inscrutable your partner may ...

Low rainfall and extreme temperatures double risk of baby elephant deaths

2013-02-04

Extremes of temperature and rainfall are affecting the survival of elephants working in timber camps in Myanmar and can double the risk of death in calves aged up to five, new research from the University of Sheffield has found.

With climate change models predicting higher temperatures and months without rainfall; this could decrease the populations of already endangered Asian elephants.

The researchers matched monthly climate records with data on birth and deaths, to track how climate variation affects the chances of elephant survival.

It is hoped this research ...

Your history may define your future: Tell your doctor

2013-02-04

Boston, MA—Your family history is important, not just because it shaped you into who you are today, but it also impacts your risk for developing cancer and other chronic diseases. For example, if one of your family members had cancer, your primary care doctor needs to know. Being able to identify individuals at increased risk can help reduce mortality. In a study published this week in the online version of the Journal of General Internal Medicine, researchers at Brigham and Women's Hospital (BWH) found that patients who use a web-based risk appraisal tool are more likely ...