(Press-News.org) If you want to read a mouse's mind, it takes some fluorescent protein and a tiny microscope implanted in the rodent's head.

Stanford scientists have demonstrated a technique for observing hundreds of neurons firing in the brain of a live mouse, in real time, and have linked that activity to long-term information storage. The unprecedented work could provide a useful tool for studying new therapies for neurodegenerative diseases such as Alzheimer's.

The researchers first used a gene therapy approach to cause the mouse's neurons to express a green fluorescent protein that was engineered to be sensitive to the presence of calcium ions. When a neuron fires, the cell naturally floods with calcium ions. Calcium stimulates the protein, causing the entire cell to fluoresce bright green.

A tiny microscope implanted just above the mouse's hippocampus – a part of the brain that is critical for spatial and episodic memory – captures the light of roughly 700 neurons. The microscope is connected to a camera chip, which sends a digital version of the image to a computer screen.

The computer then displays near real-time video of the mouse's brain activity as a mouse runs around a small enclosure, which the researchers call an arena.

The neuronal firings look like tiny green fireworks, randomly bursting against a black background, but the scientists have deciphered clear patterns in the chaos.

"We can literally figure out where the mouse is in the arena by looking at these lights," said Mark Schnitzer, an associate professor of biology and of applied physics and the senior author on the paper, recently published in the journal Nature Neuroscience.

When a mouse is scratching at the wall in a certain area of the arena, a specific neuron will fire and flash green. When the mouse scampers to a different area, the light from the first neuron fades and a new cell sparks up.

"The hippocampus is very sensitive to where the animal is in its environment, and different cells respond to different parts of the arena," Schnitzer said. "Imagine walking around your office. Some of the neurons in your hippocampus light up when you're near your desk, and others fire when you're near your chair. This is how your brain makes a representative map of a space."

The group has found that a mouse's neurons fire in the same patterns even when a month has passed between experiments. "The ability to come back and observe the same cells is very important for studying progressive brain diseases," Schnitzer said.

For example, if a particular neuron in a test mouse stops functioning, as a result of normal neuronal death or a neurodegenerative disease, researchers could apply an experimental therapeutic agent and then expose the mouse to the same stimuli to see if the neuron's function returns.

Although the technology can't be used on humans, mouse models are a common starting point for new therapies for human neurodegenerative diseases, and Schnitzer believes the system could be a very useful tool in evaluating pre-clinical research.

The work was published Feb. 10 in the online edition of Nature Neuroscience. The researchers have formed a company to manufacture and sell the device.

INFORMATION: END

CAMBRIDGE, MA -- Understanding exactly how droplets and bubbles stick to surfaces — everything from dew on blades of grass to the water droplets that form on condensing coils after steam drives a turbine in a power plant — is a "100-year-old problem" that has eluded experimental answers, says MIT's Kripa Varanasi. Furthermore, it's a question with implications for everything from how to improve power-plant efficiency to how to reduce fogging on windshields.

Now this longstanding problem has finally been licked, Varanasi says, in research he conducted with graduate student ...

There are "things hidden in plain sight" all around us. But art can help students see their world anew, unlocking discoveries in fields ranging from plant biology to biomedical imaging, according to University of Delaware professor John Jungck.

Jungck's sentiments were echoed by a panel of experts speaking on "Artful Science" on Feb. 15 at the annual meeting of the American Association for the Advancement of Science (AAAS) in Boston. Jungck organized the panel and also spoke at the event.

Canoeing on a lake near his home in northwestern Minnesota when he was a youngster, ...

Would you prefer $120 today or $154 in one year? Your answer may depend on how powerful you feel, according to new research in Psychological Science, a journal of the Association for Psychological Science.

Many people tend to forego the larger reward and opt for the $120 now, a phenomenon known as temporal discounting. But research conducted by Priyanka Joshi and Nathanael Fast of the University of Southern California Marshall School of Business suggests that people who feel powerful are more likely to wait for the bigger reward, in part because they feel a stronger connection ...

BOSTON -- Models of the human brain, patterned on engineering control theory, may some day help researchers control such neurological diseases as epilepsy, Parkinson's and migraines, according to a Penn State researcher who is using mathematical models of neuron networks from which more complex brain models emerge.

"The dual concepts of observability and controlability have been considered one of the most important developments in mathematics of the 20th century," said Steven J. Schiff, the Brush Chair Professor of Engineering and director of the Penn State Center for ...

UNIVERSITY PARK, Pa. – Identifying areas of malarial infection risk depends more on daily temperature variation than on the average monthly temperatures, according to a team of researchers, who believe that their results may also apply to environmentally temperature-dependent organisms other than the malaria parasite.

"Temperature is a key driver of several of the essential mosquito and parasite life history traits that combine to determine transmission intensity, including mosquito development rate, biting rate, development rate and survival of the parasite within the ...

Species facing widespread and rapid environmental changes can sometimes evolve quickly enough to dodge the extinction bullet. Populations of disease-causing bacteria evolve, for example, as doctors flood their "environment," the human body, with antibiotics. Insects, animals and plants can make evolutionary adaptations in response to pesticides, heavy metals and overfishing.

Previous studies have shown that the more gradual the change, the better the chances for "evolutionary rescue" – the process of mutations occurring fast enough to allow a population to avoid extinction ...

Tropical Storm Haruna came together on Feb. 19 in the Southern Indian Ocean and two NASA satellites provided visible and infrared imagery that helped forecasters see the system's organization.

A low pressure area called System 94S developed on Friday, Feb. 15 in the northern Mozambique Channel. Over the course of four days System 94S became more organized and by Feb. 19 it became Tropical Storm Haruna.

On Tuesday, Feb. 19, Tropical Storm Haruna had maximum sustained winds near 35 knots (40.2 mph/64.8 kph). Haruna was located in the Mozambique Channel, near 21.4 south ...

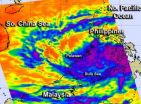

The second tropical depression of the northwestern Pacific Ocean season formed on Feb. 19, and NASA's Aqua satellite showed the storm was soaking the central and southern Philippines.

NASA's Aqua satellite passed over Tropical Depression 02W (TD02W) as it was coming together and soaking provinces in Mindanao and the Palawan province of Luzon. The Atmospheric Infrared Sounder (AIRS) instrument that flies aboard Aqua captured an infrared image of the depression at 0541 UTC (12:41 a.m. EST). The AIRS image showed very cold cloud top temperatures, colder than -63F (-52C) ...

New research out of the University of Cincinnati reveals a relatively rare look into the success of substance abuse treatment programs for African-Americans. Researchers report that self-motivation could be an important consideration into deciding on the most effective treatment strategy. The study led by Ann Kathleen Burlew, a UC professor of psychology, and LaTrice Montgomery, a UC assistant professor of human services, is published online this week in Psychology of Addictive Behaviors.

Specifically among African-Americans, the study investigated the effectiveness of ...

New York, NY (February 19, 2013) — New findings by Columbia researchers suggest that along with amyloid deposits, white matter hyperintensities (WMHs) may be a second necessary factor for the development of Alzheimer's disease.

Most current approaches to Alzheimer's disease focus on the accumulation of amyloid plaque in the brain. The researchers at the Taub Institute for Research on Alzheimer's Disease and the Aging Brain, led by Adam M. Brickman, PhD, assistant professor of neuropsychology, examined the additional contribution of small-vessel cerebrovascular disease, ...