(Press-News.org) WORCESTER, MA – Each fall millions of monarch butterflies from across the eastern United States begin a southward migration in order to escape the frigid temperatures of their northern boundaries, traveling up to 2,000 miles to an overwintering site in a specific grove of fir trees in central Mexico. Surprisingly, a new study by scientists at the University of Massachusetts Medical School published in Current Biology, suggests that exposure to coldness found in the microenvironment of the monarch's overwintering site triggers their return north every spring. Without this cold exposure, the monarch butterfly would continue flying south.

These findings help explain why monarch butterflies transverse such long distances to overwinter at a relatively small region roughly 300 square miles in size atop frost-covered mountains. Upon arrival in November, the monarchs begin to congregate in tightly packed clusters in a few isolated locations in the high altitude coniferous forests. Both the clustering and the forest cover provide a microenvironment that protects against environmental extremes – the temperature remains low enough to keep metabolic demands low but not cold enough to cause freezing – and ultimately triggers their return north in the spring.

It also suggests that these delicate creatures may be influenced by and vulnerable to global climate changes, say researchers. "The temperature of the microenvironment at the overwintering sites is a critical component for the completion of the migration cycle," said Steven M. Reppert, MD, professor of neurobiology and senior author of the study. "Without this thermal stimulus, the annual migration cycle would be broken, and we could have lost one of the most intriguing biological phenomena in the world."

Though accomplished in a single calendar year, it takes at least three generations of monarch butterflies to complete a single migratory journey. The monarchs that return to Mexico each year have never been to the overwintering sites before, and have no relatives to follow on their way. The biological and genetic mechanisms underlying their incredible journey have intrigued scientists for generations.

Earlier work by Reppert's group found that monarchs rely on a time-compensated sun compass to direct their navigation south. Their new research shows that those same systems are responsible for guiding them north each spring.

This alone, however, didn't explain what was triggering the change in direction each spring. To find out, Patrick Guerra, a postdoctoral fellow in Reppert's lab at UMass Medical School and first author on the Current Biology study, collected wild monarchs at the start of their migration in the fall and subjected the monarchs to the same temperature and light levels they would experience in their overwintering ground in Mexico. When the monarchs were studied in a flight simulator 24 days later, instead of resuming their southward journey, the butterflies headed north.

Further study confirmed that changes in temperature alone altered the flight direction of the monarch butterflies. Those subjected to cold oriented north; monarchs who were protected from the cold would continue to orient south.

These findings, coupled with newly available genetic and genomic tools for monarchs, will lead to new insights about the biological processes underlying their remarkable migratory journey.

"The more we learn, the clearer it becomes that the monarch migration is a uniquely fragile biological process," said Reppert. "Understanding how it works means we'll be better able to protect this iconic system from external threats such as global warming."

INFORMATION:

About the University of Massachusetts Medical School

The University of Massachusetts Medical School, one of the fastest growing academic health centers in the country, has built a reputation as a world-class research institution, consistently producing noteworthy advances in clinical and basic research. The Medical School attracts more than $250 million in research funding annually, 80 percent of which comes from federal funding sources. The mission of the Medical School is to advance the health and well-being of the people of the commonwealth and the world through pioneering education, research, public service and health care delivery with its clinical partner, UMass Memorial Health Care. For more information, visit www.umassmed.edu.

END

IRVINE, Calif. (February 20, 2013) – New analysis of data from the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES) , a program of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), indicates that consuming avocados may be associated with better diet quality and nutrient intake level, lower intake of added sugars, lower body weight, BMI and waist circumferences, higher "good cholesterol" levels and lower metabolic syndrome risk. These results were published in the January 2013 issue of Nutrition Journal.

Specifically, the survey data (NHANES 2001-2008, ...

DENVER (Feb. 21, 2013) – A new study from the University of Colorado Denver shows that the earliest human burial practices in Eurasia varied widely, with some graves lavish and ornate while the vast majority were fairly plain.

"We don't know why some of these burials were so ornate, but what's striking is that they postdate the arrival of modern humans in Eurasia by almost 10,000 years," said Julien Riel-Salvatore, Ph.D., assistant professor of anthropology at CU Denver and lead author of the study. "When they appear around 30,000 years ago some are lavish but many aren't ...

Disruption in the body's circadian rhythm can lead not only to obesity, but can also increase the risk of diabetes and heart disease.

That is the conclusion of the first study to show definitively that insulin activity is controlled by the body's circadian biological clock. The study, which was published on Feb. 21 in the journal Current Biology, helps explain why not only what you eat, but when you eat, matters.

The research was conducted by a team of Vanderbilt scientists directed by Professor of Biological Sciences Carl Johnson and Professors of Molecular Physiology ...

Flower colors that contrast with their background are more important to foraging bees than patterns of colored veins on pale flowers according to new research, by Heather Whitney from the University of Cambridge in the UK, and her colleagues. Their observation of how patterns of pigmentation on flower petals influence bumblebees' behavior suggests that color veins give clues to the location of the nectar. There is little to suggest, however, that bees have an innate preference for striped flowers. The work is published online in Springer's journal, Naturwissenschaften - ...

Scientists from the University of Southampton have identified the molecular system that contributes to the harmful inflammatory reaction in the brain during neurodegenerative diseases.

An important aspect of chronic neurodegenerative diseases, such as Alzheimer's, Parkinson's, Huntington's or prion disease, is the generation of an innate inflammatory reaction within the brain.

Results from the study open new avenues for the regulation of the inflammatory reaction and provide new insights into the understanding of the biology of microglial cells, which play a leading ...

A new study shows that children who are exposed to bullying during childhood are at increased risk of psychiatric disorders in adulthood, regardless of whether they are victims or perpetrators.

Professor William E. Copeland of Duke University Medical Center and Professor Dieter Wolke of the University of Warwick led a team in examining whether bullying in childhood predicts psychiatric problems and suicidality in young adulthood. While some still view bullying as a harmless rite of passage, research shows that being a victim of bullying increases the risk of adverse outcomes ...

AUGUSTA, Ga. – Early life stress like that experienced by ill newborns appears to take an early toll of the heart, affecting its ability to relax and refill with oxygen-rich blood, researchers report.

Rat pups separated from their mothers a few hours each day, experienced a significant decrease in this basic heart function when – as life tends to do – an extra stressor was added to raise blood pressure, said Dr. Catalina Bazacliu, neonatologist at the Medical College of Georgia and Children's Hospital of Georgia at Georgia Regents University. Bazacliu worked under the ...

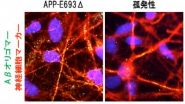

Kyoto, Japan – Working with a group from Nagasaki University, a research group at the Center for iPS Cell Research and Application (CiRA) at Japan's Kyoto University has announced in the Feb. 21 online publication of Cell Stem Cell has successfully modeled Alzheimer's disease (AD) using both familial and sporadic patient-derived induced pluripotent stem cells (iPSCs), and revealed stress phenotypes and differential drug responsiveness associated with intracellular amyloid beta oligomers in AD neurons and astrocytes.

In a study published online in Cell Stem Cell, Associate ...

People who are at greater genetic risk of schizophrenia are more likely to see a fall in IQ as they age, even if they do not develop the condition.

Scientists at the University of

Edinburgh say the findings could lead to new research into how different genes for schizophrenia affect brain function over time. They also show that genes associated with schizophrenia influence people in other important ways besides causing the illness itself.

The researchers used the latest genetic analysis techniques to reach their conclusion on how thinking skills change with age.

They ...

Brussels and Geneva, 20th February 2013 --- Major progress has been made in the past 30 years in the knowledge and management of liver disease, yet approximately 29 million Europeans still suffer from a chronic liver condition.

The European Association for the Study of the Liver (EASL) today unveiled its new publication The burden of liver disease in Europe: a review of available epidemiological data. Key findings in the report suggest that alcohol consumption, viral hepatitis B and C and metabolic syndromes related to overweight and obesity are the leading causes of ...