(Press-News.org) GAINESVILLE, Fla. — University of Florida paleontologists have discovered remarkably well-preserved fossils of two crocodilians and a mammal previously unknown to science during recent Panama Canal excavations that began in 2009.

The two new ancient extinct alligator-like animals and an extinct hippo-like species inhabited Central America during the Miocene about 20 million years ago. The research expands the range of ancient animals in the subtropics — some of the most diverse areas today about which little is known historically because lush vegetation prevents paleontological excavations — and may be used to better understand how climate change affects species dispersal today. The two studies appear online today in the same issue of the Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology.

The fossils shed new light on scientists' understanding of species distribution because they represent a time before the formation of the Isthmus of Panama, when the continents of North and South America were separated by oceanic waters.

"In part we are trying to understand how ecosystems have responded to animals moving long distances and across geographic barriers in the past," said study co-author Jonathan Bloch, associate curator of vertebrate paleontology at the Florida Museum of Natural History on the UF campus. "It's a testing ground for things like invasive species – if you have things that migrated from one place into another in the past, then potentially you have the ability to look at what impact a new species might have on an ecosystem in the future."

The research was funded by the National Science Foundation Panama Canal Partnerships in International Research and Education project, which supports paleontological excavation of the canal during construction expected to continue through 2014.

"We're very fortunate we could get the funding for PIRE to take advantage of this opportunity — we're getting to sample these areas that are completely unsampled," said Alex Hastings, lead author of the crocodilian study and a visiting instructor at Georgia Southern University who conducted the research for the project as a UF graduate student.

Researchers analyzed all known crocodilian fossils from the Panama Canal, including the oldest records of Central American caimans, which are cousins of alligators. The more primitive species, named Culebrasuchus mesoamericanus, may represent an evolutionary transition between caimans and alligators, Hastings said.

"You mix an alligator and one of the more primitive caimans and you end up with this caiman that has a much flatter snout, making it more like an alligator," Hastings said. "Before this, there were no fossil crocodilian skulls known from Central America."

Christopher Brochu, an assistant professor of vertebrate paleontology in the department of geoscience at the University of Iowa, said "the caiman fossil record is tantalizing," and the new data shows there is still a long way to go before researchers understand the group.

"The fossils that are in this paper are from a later time period, but some of them appear to be earlier-branching groups, which could be very important," said Brochu, who was not involved with the study. "The problem is, because we know so little about early caiman history, it's very difficult to tell where these later forms actually go on the family tree."

The new mammal species researchers described is an anthracothere, Arretotherium meridionale, an even-toed hooved mammal previously thought to be related to living hippos and intensively studied on the basis of its hypothetical relationship with whales. About the size of a cow, the mammal would have lived in a semi-aquatic environment in Central America, said lead author and UF graduate student Aldo Rincon.

"With the evolution of new terrestrial corridors like this peninsula connecting North America with Central America, this is one of the most amazing examples of the different kind of paths land animals can take," Rincon said. "Somehow this anthracothere is similar to anthracotheres from other continents like northern Africa and northeastern Asia."

Researchers also name a second crocodilian species, Centenariosuchus gilmorei, after Charles Gilmore, who first reported evidence of crocodilian fossils collected during construction of the canal 100 years ago. The genus is named in honor of the canal's centennial in 2014.

Researchers will continue excavating deposits from the Panama Canal during construction to widen and straighten the channel and build new locks. The project is funded by a $3.8 million NSF grant to develop partnerships between the U.S. and Panama and engage the next generation of scientists in paleontological and geological discoveries along the canal.

INFORMATION:

Study co-authors include Bruce MacFadden of UF and Carlos Jaramillo of the Smithsonian Tropical Research Institute.

Credits

Writer

Danielle Torrent, dtorrent@flmhh.ufl.edu

Source

Jonathan Bloch, jbloch@flmnh.ufl.edu

Source

Aldo Rincon, arincon@ufl.edu

Source

Alex Hastings, akh@ufl.edu

END

New research from Rice University, Baylor College of Medicine (BCM) and the Puget Sound Blood Center (PSBC) has revealed how stresses of flow in the small blood vessels of the heart and brain could cause a common protein to change shape and form dangerous blood clots. The scientists were surprised to find that the proteins could remain in the dangerous, clot-initiating shape for up to five hours before returning to their normal, healthy shape.

The study -- the first of its kind -- focused on a protein called von Willebrand factor, or VWF, a key player in clot formation. ...

(Boston) – Researchers at Boston University School of Medicine (BUSM) have, for the first time, identified a specific group of cells in the brainstem whose activation during rapid eye movement (REM) sleep is critical for the regulation of emotional memory processing. The findings, published in the Journal of Neuroscience, could help lead to the development of effective behavioral and pharmacological therapies to treat anxiety disorders, such as post-traumatic stress disorder, phobias and panic attacks.

There are two main stages of sleep – REM and non-REM – and both are ...

Ann Arbor, Mich. — Each year, more than 130,000 children younger than 13 are treated in U.S. emergency departments after motor-vehicle crash-related injuries.

Each of these visits offer a chance to pass along tips for proper use of child passenger restraints, but a new study from the University of Michigan indicates emergency departments may not be taking advantage of those opportunities.

In the study published today in Pediatric Emergency Care, more than one-third of ER physicians say they are uncertain whether their departments provide information about child passenger ...

WASHINGTON, D.C. — Women's issues play a major role in the health of the nation and should be a key consideration for policymakers as they design and set up the new insurance exchanges, according to a report co-authored by policy experts at the George Washington University School of Public Health and Health Services (SPHHS). The report offers a checklist for the state-based health insurance exchanges, one that will help ensure that women, children and family members can get the services they need to prevent costly and debilitating medical problems.

"Women often use a ...

PHILADELPHIA - Omega-3 fatty acids found in oily fish may have diverse health-promoting effects, potentially protecting the immune, nervous, and cardiovascular systems.

But how the health effects of one such fatty acid -- docosahexaenoic acid (DHA) -- works remains unclear, in part because its molecular signaling pathways are only now being understood.

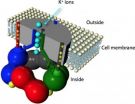

Toshinori Hoshi, PhD, professor of Physiology, at the Perelman School of Medicine, University of Pennsylvania, and colleagues showed, in two papers out this week in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, ...

BETHESDA, MD – March 5, 2013 -- A team of European scientists from the University Medical Center Hamburg-Eppendorf (UKE) and the Cologne Excellence Cluster on Cellular Stress Responses in Aging-Associated Diseases (CECAD) at the University of Cologne in Germany has taken an important step closer to understanding the root cause of age-related dementia. In research involving both worms and mice, they have found that age-related dementia is likely the result of a declining ability of neurons to dispose of unwanted aggregated proteins. As protein disposal becomes significantly ...

In Africa and Thailand, communities that worked together on HIV-prevention efforts saw not only a rise in HIV screening but a drop in new infections, according to a new study presented this week at the Conference on Retroviruses and Opportunistic Infections in Atlanta.

The U.S. National Institute of Mental Health's Project Accept — a trial conducted by the HIV Prevention Trials Network to test a combination of social, behavioral and structural HIV-prevention interventions — demonstrated that a series of community efforts was able to boost the number of people tested ...

Chevy Chase, MD—In a Position Statement unveiled today, The Endocrine Society advocates that all methods for measuring estrogens, which play a crucial role in human biology, be made traceable to a common standard.

In addition to the well-known role of estrogens in sexual development, these hormones, particularly estradiol, have a significant impact on the health of the skin, blood vessels, bones, muscle, kidney, liver, digestive system, brain, lung and pancreas. Studies have linked changes in estradiol levels to coronary artery disease, stroke and breast cancer.

"Estradiol ...

AMHERST, Mass. – Biochemists at the University of Massachusetts Amherst including assistant professor Peter Chien recently gained new insight into how protein synthesis and degradation help to regulate the delicate ballet of cell division. In particular, they reveal how two proteins shelter each other in "mutually assured cleanup" to insure that division goes smoothly and safely.

Cells must routinely dispose of leftover proteins with the aid of proteases that cut up and recycle used proteins. The problem for biochemists is that the same protein molecule can be toxic garbage ...

A new report published today concludes that nearly half of Africa's wild lion populations may decline to near extinction over the next 20-40 years without urgent conservation measures. The plight of many lion populations is so bleak, the report concludes that fencing them in - and fencing humans out - may be their only hope for survival.

Led by the University of Minnesota's Professor Craig Packer and co-authored by a large team of lion biologists, including Panthera's President, Dr. Luke Hunter, and Lion Program Director, Dr. Guy Balme, the report, entitled Conserving ...