(Press-News.org) PROVIDENCE, R.I. [Brown University] — Scientists are using ever more complex models running on ever more powerful computers to simulate the earth's climate. But new research suggests that basic physics could offer a simpler and more meaningful way to model key elements of climate.

The research, published in the journal Physical Review Letters, shows that a technique called direct statistical simulation does a good job of modeling fluid jets, fast-moving flows that form naturally in oceans and in the atmosphere. Brad Marston, professor of physics at Brown University and one of the authors of the paper, says the findings are a key step toward bringing powerful statistical models rooted in basic physics to bear on climate science.

In addition to the Physical Review Letters paper, Marston will report on the work at a meeting of the American Physical Society to be held in Baltimore this later month.

The method of simulation used in climate science now is useful but cumbersome, Marston said. The method, known as direct numerical simulation, amounts to taking a modified weather model and running it through long periods of time. Moment-to-moment weather — rainfall, temperatures, wind speeds at a given moment, and other variables — is averaged over time to arrive at the climate statistics of interest. Because the simulations need to account for every weather event along the way, they are mind-bogglingly complex, take a long time run, and require the world's most powerful computers.

Direct statistical simulation, on the other hand, is a new way of looking at climate. "The approach we're investigating," Marston said, "is the idea that one can directly find the statistics without having to do these lengthy time integrations."

It's a bit like the approach physicists use to describe the behavior of gases.

"Say you wanted to describe the air in a room," Marston said. "One way to do it would be to run a giant supercomputer simulation of all the positions of all of the molecules bouncing off of each other. But another way would be to develop statistical mechanics and find that the gas actually obeys simple laws you can write down on a piece of paper: PV=nRT, the gas equation. That's a much more useful description, and that's the approach we're trying to take with the climate."

Conceptually, the technique focuses attention on fundamental forces driving climate, instead of "following every little swirl," Marston said. A practical advantage would be the ability to model climate conditions from millions of years ago without having to reconstruct the world's entire weather history in the process.

The theoretical basis for direct statistical simulation has been around for nearly 50 years. The problem, however, is that the mathematical and computational tools to apply the idea to climate systems aren't fully developed. That is what Marston and his collaborators have been working on for the last few years, and the results in this new paper show their techniques have good potential.

The paper, which Marston wrote with University of Leeds mathematician Steve Tobias, investigates whether direct statistical simulation is useful in describing the formation and characteristics of fluid jets, narrow bands of fast-moving fluid that move in one direction. Jets form naturally in all kinds of moving fluids, including atmospheres and oceans. On Earth, atmospheric jet streams are major drivers of storm tracks.

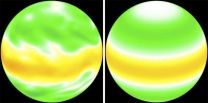

For their study, Marston and Tobias simulated the jets that form as a fluid moves on a hypothetical spinning sphere. They modeled the fluid using both the traditional numerical technique and their statistical technique, and then compared the output of the two models. They found that the models generally arrived at similar values for the number of jets that would form and the strength of the airflow, demonstrating that statistical simulation can indeed be used to model jets.

There were limits, however, to what the statistical model could do. The study found that as pace of adding and removing energy to the fluid system increased, the statistical model started to break down. Marston and Tobias are currently working on an expansion of their technique to deal with that problem.

Despite the limitation, Marston is upbeat about the potential for the technique. "We're very pleased that it works as well as it did here," he said.

Since completing the study, Marston has integrated the method into a computer program called "GCM" that he has made easily available via Apple's Mac App Store for other researchers to download. The program allows users to build their own simulations, comparing numerical and statistical models. Marston expects that researchers who are interested in this field will download it and play with the technique on their own, providing new insights along the way. "I'm hoping that citizen-scientists will also explore climate modeling with it as well, and perhaps make a discovery or two," he said.

There's much more work to be done on this, Marston stresses, both in solving the energy problem and in scaling the technique to model more realistic climate systems. At this point, the simulations have only been applied to hypothetical atmospheres with one or two layers. The Earth's atmosphere is a bit more complex than that.

"The research is at a very early stage," Marston said, "but it's picking up steam."

INFORMATION:

Statistical physics offers a new way to look at climate

2013-03-06

ELSE PRESS RELEASES FROM THIS DATE:

Green tea extract interferes with the formation of amyloid plaques in Alzheimer's disease

2013-03-06

ANN ARBOR—Researchers at the University of Michigan have found a new potential benefit of a molecule in green tea: preventing the misfolding of specific proteins in the brain.

The aggregation of these proteins, called metal-associated amyloids, is associated with Alzheimer's disease and other neurodegenerative conditions.

A paper published recently in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences explained how U-M Life Sciences Institute faculty member Mi Hee Lim and an interdisciplinary team of researchers used green tea extract to control the generation of metal-associated ...

Biomass analysis tool is faster, more precise

2013-03-06

A screening tool from the U.S. Department of Energy's National Renewable Energy Laboratory (NREL) eases and greatly quickens one of the thorniest tasks in the biofuels industry: determining cell wall chemistry to find plants with ideal genes.

NREL's new High-Throughput Analytical Pyrolysis tool (HTAP) can thoroughly analyze hundreds of biomass samples a day and give an early look at the genotypes that are most worth pursuing. Analysis of a sample that previously took two weeks can now be done in two minutes. That is potentially game changing for tree nurseries and the ...

Hurting someone else can hurt you just as much

2013-03-06

Experiencing ostracism — being deliberately ignored or excluded — hurts, but ostracizing someone else could hurt just as much, according to new research published in Psychological Science, a journal of the Association for Psychological Science.

Humans are social animals and they typically avoid causing harm to others when they can. But past experiments — and real-life events — suggest that people are willing to inflict harm in order to comply with authorities.

Graduate student Nicole Legate, along with her advisor, Richard Ryan of the University of Rochester, and colleagues, ...

Pain training for primary care providers

2013-03-06

Patients who experience chronic pain may experience improvement in symptoms if their primary care providers are specifically trained in multiple aspects of pain, including emotional consequences.

A collaborative team headed by Thomas C. Chelimsky, M.D., professor and chairman of the department of neurology at the Medical College of Wisconsin, conducted a pilot study assessing the Primary Practice Physician Program for Chronic Pain (4PCP) and its impact on both patients and providers.

The findings are published in the Clinical Journal of Pain, http://journals.lww.com/clinicalpain/toc/publishahead.

Chronic ...

UF scientists discover new crocodilian, hippo-like species from Panama

2013-03-06

GAINESVILLE, Fla. — University of Florida paleontologists have discovered remarkably well-preserved fossils of two crocodilians and a mammal previously unknown to science during recent Panama Canal excavations that began in 2009.

The two new ancient extinct alligator-like animals and an extinct hippo-like species inhabited Central America during the Miocene about 20 million years ago. The research expands the range of ancient animals in the subtropics — some of the most diverse areas today about which little is known historically because lush vegetation prevents paleontological ...

Stressed proteins can cause blood clots for hours

2013-03-06

New research from Rice University, Baylor College of Medicine (BCM) and the Puget Sound Blood Center (PSBC) has revealed how stresses of flow in the small blood vessels of the heart and brain could cause a common protein to change shape and form dangerous blood clots. The scientists were surprised to find that the proteins could remain in the dangerous, clot-initiating shape for up to five hours before returning to their normal, healthy shape.

The study -- the first of its kind -- focused on a protein called von Willebrand factor, or VWF, a key player in clot formation. ...

BUSM study reveals potential target to better treat, cure anxiety disorders

2013-03-06

(Boston) – Researchers at Boston University School of Medicine (BUSM) have, for the first time, identified a specific group of cells in the brainstem whose activation during rapid eye movement (REM) sleep is critical for the regulation of emotional memory processing. The findings, published in the Journal of Neuroscience, could help lead to the development of effective behavioral and pharmacological therapies to treat anxiety disorders, such as post-traumatic stress disorder, phobias and panic attacks.

There are two main stages of sleep – REM and non-REM – and both are ...

Emergency departments not doing enough to educate parents about car seat safety

2013-03-06

Ann Arbor, Mich. — Each year, more than 130,000 children younger than 13 are treated in U.S. emergency departments after motor-vehicle crash-related injuries.

Each of these visits offer a chance to pass along tips for proper use of child passenger restraints, but a new study from the University of Michigan indicates emergency departments may not be taking advantage of those opportunities.

In the study published today in Pediatric Emergency Care, more than one-third of ER physicians say they are uncertain whether their departments provide information about child passenger ...

Women's health must be priority for state health exchange marketplaces, new report says

2013-03-06

WASHINGTON, D.C. — Women's issues play a major role in the health of the nation and should be a key consideration for policymakers as they design and set up the new insurance exchanges, according to a report co-authored by policy experts at the George Washington University School of Public Health and Health Services (SPHHS). The report offers a checklist for the state-based health insurance exchanges, one that will help ensure that women, children and family members can get the services they need to prevent costly and debilitating medical problems.

"Women often use a ...

Omega-3s from fish vs. fish oil pills better at maintaining blood pressure in mouse model

2013-03-06

PHILADELPHIA - Omega-3 fatty acids found in oily fish may have diverse health-promoting effects, potentially protecting the immune, nervous, and cardiovascular systems.

But how the health effects of one such fatty acid -- docosahexaenoic acid (DHA) -- works remains unclear, in part because its molecular signaling pathways are only now being understood.

Toshinori Hoshi, PhD, professor of Physiology, at the Perelman School of Medicine, University of Pennsylvania, and colleagues showed, in two papers out this week in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, ...