(Press-News.org) CHAMPAIGN, Ill. — Ribosomes, the cellular machines that build proteins, are themselves made up of dozens of proteins and a few looping strands of RNA. A new study, reported in the journal Nature, offers new clues about how the ribosome, the master assembler of proteins, also assembles itself.

"The ribosome has more than 50 different parts – it has the complexity of a sewing machine in terms of the number of parts," said University of Illinois physics professor Taekjip Ha, who led the research with U. of I. chemistry professor Zaida Luthey-Schulten and Johns Hopkins University biophysics professor Sarah Woodson. "A sewing machine assembles other things but it cannot assemble itself if you have the parts lying around," Ha said. "The ribosome, however, can do that. It's quite amazing."

In 2000, scientists published precise atomic structures of intact ribosomes (a feat that won them a 2009 Nobel Prize in chemistry) and for decades researchers have delved into the mechanics of ribosome function. But scientists have much to learn about how the ribosome itself is built from its component parts, Luthey-Schulten said.

Solving the atomic structure was a huge step forward "that tells us what the ribosome looks like once it's assembled," she said. "But it doesn't tell you anything about how it gets there, how all these parts come together."

All ribosomes consist of two subunits, each a cluster of precisely folded proteins and RNA. The team focused on the small ribosomal subunit of the E. coli bacterium. It is made up of about 20 proteins and a ribosomal RNA (known as 16S).

The researchers labeled one of those ribosomal proteins. Known as S4, it is thought to be the first to interact with the 16S RNA during assembly. They also labeled two sites on the 16S RNA. Each label fluoresced a different color, and was designed to glow more brightly when in close proximity to another label (a technology known as FRET). These signals offered clues about how the RNA and proteins were interacting.

The team was most interested in a central region of the 16s RNA because it contains signature sequences that differentiate the three cellular "domains," or superkingdoms, of life. Previous studies suggested that this region also was key to the RNA-protein interactions that occur in the earliest stages of ribosome assembly.

Using a "computational microscope," the team compared data from their FRET experiments with an all-atom simulation of the protein and RNA interaction. Their analysis revealed that the S4 protein and the 16S ribosomal RNA were a surprisingly "dynamic duo," Ha said. The protein constrained the RNA somewhat, but still allowed it to undulate and change its conformation.

The team found that the S4 protein tends to bind to the RNA when the RNA takes on an unusual conformation – one not seen in the fully assembled ribosome. This was a surprise, since scientists generally assume that ribosomal proteins lock RNA into its final, three-dimensional shape.

"We found that the S4 and RNA complex is not static," Ha said. "It actually is dynamic and that dynamism is likely to allow binding of the next protein" in the sequence of ribosome assembly.

"Once the S4 binds, it induces other conformational changes that allow the binding sites for other proteins to appear," he said. "So the binding site for the third protein doesn't appear until after the second protein is there."

This intricate dance of molecules leading to the assembly of ribosomes occurs very fast, Luthey-Schulten said.

"You can go from as few as 1,000 to 30,000 ribosomes in a bacterial cell during its cell cycle," she said. "More than 80 percent of the RNA that's in the cell is in the ribosomes."

Knowing how the ribosome is put together offers new antibiotic targets, said Ha, who is a Howard Hughes Medical Institute investigator and a co-director of the Center for the Physics of Living Cells at Illinois.

"Instead of waiting until your enemy has fully assembled its army, you want to intervene early to prevent that from happening," he said. "We know that this protein/RNA region has unique signatures in bacteria, so maybe we can target this process while keeping the human ribosome intact."

INFORMATION:

Luthey-Schulten and Ha are affiliates of the Institute for Genomic Biology and the Beckman Institute at the U. of I.

The National Science Foundation and HHMI funded this project.

Editor's notes:

To reach Taekjip Ha, call 217-265-0717; email tjha@illinois.edu.

To reach Zaida Luthey-Schulten, call 217-333-3518; email zan@illinois.edu.

The paper, "Protein-Guided Dynamics During Early Ribosome

Assembly," is available to members of the media from the U. of I. News

Bureau.

Advanced techniques yield new insights into ribosome self-assembly

2014-02-13

ELSE PRESS RELEASES FROM THIS DATE:

Teledermatology app system offers efficiencies, reliably prioritizes inpatient consults

2014-02-13

PHILADELPHIA - A new Penn Medicine study shows that remote consultations from dermatologists using a secure smart phone app are reliable at prioritizing care for hospitalized patients with skin conditions. Researchers in the Perelman School of Medicine at the University of Pennsylvania report in JAMA Dermatology that this teledermatology process is reliable and can help deliver care more efficiently in busy academic hospitals and potentially in community hospital settings.

A national shortage and uneven distribution of dermatologists in the United States has caused scheduling ...

Stirring-up atomtronics in a quantum circuit

2014-02-13

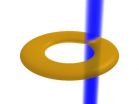

VIDEO:

This is an animation showing a laser beam stirring a ring shaped quantum gas.

Click here for more information.

Atomtronics is an emerging technology whereby physicists use ensembles of atoms to build analogs to electronic circuit elements. Modern electronics relies on utilizing the charge properties of the electron. Using lasers and magnetic fields, atomic systems can be engineered to have behavior analogous to that of electrons, making them an exciting platform for studying ...

Ancient settlements and modern cities follow same rules of development, says CU-Boulder

2014-02-13

Recently derived equations that describe development patterns in modern urban areas appear to work equally well to describe ancient cities settled thousands of years ago, according to a new study led by a researcher at the University of Colorado Boulder.

"This study suggests that there is a level at which every human society is actually very similar," said Scott Ortman, assistant professor of anthropology at CU-Boulder and lead author of the study published in the journal PLOS ONE. "This awareness helps break down the barriers between the past and present and allows us ...

America's only Clovis skeleton had its genome mapped

2014-02-13

They lived in America about 13,000 years ago where they hunted mammoth, mastodons and giant bison with big spears. The Clovis people were not the first humans in America, but they represent the first humans with a wide expansion on the North American continent – until the culture mysteriously disappeared only a few hundred years after its origin. Who the Clovis people were and which present day humans they are related to has been discussed intensely and the issue has a key role in the discussion about how the Americas were peopled. Today there exists only one human skeleton ...

New target for psoriasis treatment discovered

2014-02-13

Researchers at King's College London have identified a new gene (PIM1), which could be an effective target for innovative treatments and therapies for the human autoimmune disease, psoriasis.

Psoriasis affects around 2 per cent of people in the UK and causes dry, red lesions on the skin which can become sore or itchy and can have significant impact on the sufferer's quality of life.

It is thought that psoriasis is caused by a problem with the body's immune system in which new skin cells are created too rapidly, causing a build up of flaky patches on the skin's surface. ...

Two parents with Alzheimer's disease? Disease may show up decades early on brain scans

2014-02-13

MINNEAPOLIS – People who are dementia-free but have two parents with Alzheimer's disease may show signs of the disease on brain scans decades before symptoms appear, according to a new study published in the February 12, 2014, online issue of Neurology®, the medical journal of the American Academy of Neurology.

"Studies show that by the time people come in for a diagnosis, there may be a large amount of irreversible brain damage already present," said study author Lisa Mosconi, PhD, with the New York University School of Medicine in New York. "This is why it is ideal ...

Solving an evolutionary puzzle

2014-02-13

For four decades, waste from nearby manufacturing plants flowed into the waters of New Bedford Harbor—an 18,000-acre estuary and busy seaport. The harbor, which is contaminated with polychlorinated biphenyls (PCBs) and heavy metals, is one of the EPA's largest Superfund cleanup sites.

It's also the site of an evolutionary puzzle that researchers at Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution (WHOI) and their colleagues have been working to solve.

Atlantic killifish—common estuarine fishes about three inches long—are not only tolerating the toxic conditions in the harbor, they ...

NIF experiments show initial gain in fusion fuel

2014-02-13

LIVERMORE, Calif. – Ignition – the process of releasing fusion energy equal to or greater than the amount of energy used to confine the fuel – has long been considered the "holy grail" of inertial confinement fusion science. A key step along the path to ignition is to have "fuel gains" greater than unity, where the energy generated through fusion reactions exceeds the amount of energy deposited into the fusion fuel.

Though ignition remains the ultimate goal, the milestone of achieving fuel gains greater than 1 has been reached for the first time ever on any facility. ...

Well-child visits linked to more than 700,000 subsequent flu-like illnesses

2014-02-13

CHICAGO (February 12, 2014) – New research shows that well-child doctor appointments for annual exams and vaccinations are associated with an increased risk of flu-like illnesses in children and family members within two weeks of the visit. This risk translates to more than 700,000 potentially avoidable illnesses each year, costing more than $490 million annually. The study was published in the March issue of Infection Control and Hospital Epidemiology, the journal of the Society for Healthcare Epidemiology of America.

"Well child visits are critically important. However, ...

'Viewpoint' addresses IOM report on genome-based therapeutics and companion diagnostics

2014-02-13

The promise of personalized medicine, says University of Vermont (UVM) molecular pathologist Debra Leonard, M.D., Ph.D., is the ability to tailor therapy based on markers in the patient's genome and, in the case of cancer, in the cancer's genome. Making this determination depends on not one, but several genetic tests, but the system guiding the development of those tests is complex, and plagued with challenges.

In a February 12, 2014 Online First Journal of the American Medical Association "Viewpoint" article, Leonard and colleagues address this issue in conjunction ...