(Press-News.org) A team of French and Swedish researchers have presented new fossil evidence for the origin of one of the most important and emotionally significant parts of our anatomy: the face. Using micron resolution X-ray imaging, they show how a series of fossils, with a 410 million year old armoured fish called Romundina at its centre, documents the step-by-step assembly of the face during the evolutionary transition from jawless to jawed vertebrates. The research is published in Nature on 12 February 2014.

Vertebrates, or backboned animals, come in two basic models: jawless and jawed. Today, the only jawless vertebrates are lampreys and hagfishes, whereas jawed vertebrates number more than fifty thousand species, including ourselves. It is known that jawed vertebrates evolved from jawless ones, a dramatic anatomical transformation that effectively turned the face inside out.

VIDEO:

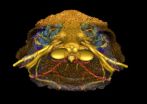

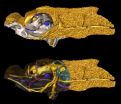

In this video sequence, different transparencies provide an ensemble view of the blood vessel network (red: arteries; blue: veins), nerves and endocranial cavity (yellow), shape of telencephalon, nasal sacs and...

Click here for more information.

In embryos of jawless vertebrates, blocks of tissue grow forward on either side of the brain, meeting in the midline at the front to create a big upper lip surrounding a single midline "nostril" that lies just in front of the eyes. In jawed vertebrates, this same tissue grows forward in the midline under the brain, pushing between the left and right nasal sacs which open separately to the outside. This is why our face has two nostrils rather than a single big hole in the middle. The front part of the brain is also much longer in jawed vertebrates, with the result that our nose is positioned at the front of the face rather than far back between our eyes.

Until now, very little has been known about the intermediate steps of this strange transformation. The scientists studied the skull of Romundina, an early armoured fish with jaws, or placoderm, from arctic Canada. The skull is part of a collection of the French National Natural History Museum in Paris.

Romundina has separate left and right nostrils, but they sit far back, behind an upper lip like that of a jawless vertebrate. "This skull is a mix of primitive and modern features, making it an invaluable intermediate fossil between jawless and jawed vertebrates", says Vincent Dupret of Uppsala University, one of two lead authors of the study.

By imaging the internal structure of the skull using high-energy X-rays at the European Synchrotron (ESRF) in Grenoble, France, the authors show that the skull housed a brain with a short front end, very similar to that of a jawless vertebrate.

"In effect, Romundina has the construction of a jawed vertebrate but the proportions of a jawless one", says Per Ahlberg, of Uppsala University and the other lead author of the study. "This shows us that the organization of the major tissue blocks was the first thing to change, and that the shape of the head caught up afterwards", he adds.

By placing Romundina in a sequence of other fossil fishes, some more primitive and some more advanced, the authors were able to map out all the main steps of the transition.

"Without the intense X-rays produced at the ESRF, we would not have been able to create a virtual representation of the internal structures of the skull" said Sophie Sanchez from The European Synchrotron (ESRF) in Grenoble.

INFORMATION: END

Jaw dropping: scientists reveal how vertebrates came to have a face

Synchrotron X-rays provide new fossil evidence

2014-02-13

ELSE PRESS RELEASES FROM THIS DATE:

Advanced techniques yield new insights into ribosome self-assembly

2014-02-13

CHAMPAIGN, Ill. — Ribosomes, the cellular machines that build proteins, are themselves made up of dozens of proteins and a few looping strands of RNA. A new study, reported in the journal Nature, offers new clues about how the ribosome, the master assembler of proteins, also assembles itself.

"The ribosome has more than 50 different parts – it has the complexity of a sewing machine in terms of the number of parts," said University of Illinois physics professor Taekjip Ha, who led the research with U. of I. chemistry professor Zaida Luthey-Schulten and Johns Hopkins University ...

Teledermatology app system offers efficiencies, reliably prioritizes inpatient consults

2014-02-13

PHILADELPHIA - A new Penn Medicine study shows that remote consultations from dermatologists using a secure smart phone app are reliable at prioritizing care for hospitalized patients with skin conditions. Researchers in the Perelman School of Medicine at the University of Pennsylvania report in JAMA Dermatology that this teledermatology process is reliable and can help deliver care more efficiently in busy academic hospitals and potentially in community hospital settings.

A national shortage and uneven distribution of dermatologists in the United States has caused scheduling ...

Stirring-up atomtronics in a quantum circuit

2014-02-13

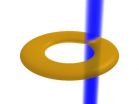

VIDEO:

This is an animation showing a laser beam stirring a ring shaped quantum gas.

Click here for more information.

Atomtronics is an emerging technology whereby physicists use ensembles of atoms to build analogs to electronic circuit elements. Modern electronics relies on utilizing the charge properties of the electron. Using lasers and magnetic fields, atomic systems can be engineered to have behavior analogous to that of electrons, making them an exciting platform for studying ...

Ancient settlements and modern cities follow same rules of development, says CU-Boulder

2014-02-13

Recently derived equations that describe development patterns in modern urban areas appear to work equally well to describe ancient cities settled thousands of years ago, according to a new study led by a researcher at the University of Colorado Boulder.

"This study suggests that there is a level at which every human society is actually very similar," said Scott Ortman, assistant professor of anthropology at CU-Boulder and lead author of the study published in the journal PLOS ONE. "This awareness helps break down the barriers between the past and present and allows us ...

America's only Clovis skeleton had its genome mapped

2014-02-13

They lived in America about 13,000 years ago where they hunted mammoth, mastodons and giant bison with big spears. The Clovis people were not the first humans in America, but they represent the first humans with a wide expansion on the North American continent – until the culture mysteriously disappeared only a few hundred years after its origin. Who the Clovis people were and which present day humans they are related to has been discussed intensely and the issue has a key role in the discussion about how the Americas were peopled. Today there exists only one human skeleton ...

New target for psoriasis treatment discovered

2014-02-13

Researchers at King's College London have identified a new gene (PIM1), which could be an effective target for innovative treatments and therapies for the human autoimmune disease, psoriasis.

Psoriasis affects around 2 per cent of people in the UK and causes dry, red lesions on the skin which can become sore or itchy and can have significant impact on the sufferer's quality of life.

It is thought that psoriasis is caused by a problem with the body's immune system in which new skin cells are created too rapidly, causing a build up of flaky patches on the skin's surface. ...

Two parents with Alzheimer's disease? Disease may show up decades early on brain scans

2014-02-13

MINNEAPOLIS – People who are dementia-free but have two parents with Alzheimer's disease may show signs of the disease on brain scans decades before symptoms appear, according to a new study published in the February 12, 2014, online issue of Neurology®, the medical journal of the American Academy of Neurology.

"Studies show that by the time people come in for a diagnosis, there may be a large amount of irreversible brain damage already present," said study author Lisa Mosconi, PhD, with the New York University School of Medicine in New York. "This is why it is ideal ...

Solving an evolutionary puzzle

2014-02-13

For four decades, waste from nearby manufacturing plants flowed into the waters of New Bedford Harbor—an 18,000-acre estuary and busy seaport. The harbor, which is contaminated with polychlorinated biphenyls (PCBs) and heavy metals, is one of the EPA's largest Superfund cleanup sites.

It's also the site of an evolutionary puzzle that researchers at Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution (WHOI) and their colleagues have been working to solve.

Atlantic killifish—common estuarine fishes about three inches long—are not only tolerating the toxic conditions in the harbor, they ...

NIF experiments show initial gain in fusion fuel

2014-02-13

LIVERMORE, Calif. – Ignition – the process of releasing fusion energy equal to or greater than the amount of energy used to confine the fuel – has long been considered the "holy grail" of inertial confinement fusion science. A key step along the path to ignition is to have "fuel gains" greater than unity, where the energy generated through fusion reactions exceeds the amount of energy deposited into the fusion fuel.

Though ignition remains the ultimate goal, the milestone of achieving fuel gains greater than 1 has been reached for the first time ever on any facility. ...

Well-child visits linked to more than 700,000 subsequent flu-like illnesses

2014-02-13

CHICAGO (February 12, 2014) – New research shows that well-child doctor appointments for annual exams and vaccinations are associated with an increased risk of flu-like illnesses in children and family members within two weeks of the visit. This risk translates to more than 700,000 potentially avoidable illnesses each year, costing more than $490 million annually. The study was published in the March issue of Infection Control and Hospital Epidemiology, the journal of the Society for Healthcare Epidemiology of America.

"Well child visits are critically important. However, ...

LAST 30 PRESS RELEASES:

Teens using AI meal plans could be eating too few calories — equivalent to skipping a meal

Inconsistent labeling and high doses found in delta-8 THC products: JSAD study

Bringing diabetes treatment into focus

Iowa-led research team names, describes new crocodile that hunted iconic Lucy’s species

One-third of Americans making financial trade-offs to pay for healthcare

Researchers clarify how ketogenic diets treat epilepsy, guiding future therapy development

PsyMetRiC – a new tool to predict physical health risks in young people with psychosis

Island birds reveal surprising link between immunity and gut bacteria

Research presented at international urology conference in London shows how far prostate cancer screening has come

Further evidence of developmental risks linked to epilepsy drugs in pregnancy

Cosmetic procedures need tighter regulation to reduce harm, argue experts

How chaos theory could turn every NHS scan into its own fortress

Vaccine gaps rooted in structural forces, not just personal choices: SFU study

Safer blood clot treatment with apixaban than with rivaroxaban, according to large venous thrombosis trial

Turning herbal waste into a powerful tool for cleaning heavy metal pollution

Immune ‘peacekeepers’ teach the body which foods are safe to eat

AAN issues guidance on the use of wearable devices

In former college athletes, more concussions associated with worse brain health

Racial/ethnic disparities among people fatally shot by U.S. police vary across state lines

US gender differences in poverty rates may be associated with the varying burden of childcare

3D-printed robotic rattlesnake triggers an avoidance response in zoo animals, especially species which share their distribution with rattlers in nature

Simple ‘cocktail’ of amino acids dramatically boosts power of mRNA therapies and CRISPR gene editing

Johns Hopkins scientists engineer nanoparticles able to seek and destroy diseased immune cells

A hidden immune circuit in the uterus revealed: Findings shed light on preeclampsia and early pregnancy failure

Google Earth’ for human organs made available online

AI assistants can sway writers’ attitudes, even when they’re watching for bias

Still standing but mostly dead: Recovery of dying coral reef in Moorea stalls

3D-printed rattlesnake reveals how the rattle is a warning signal

Despite their contrasting reputations, bonobos and chimpanzees show similar levels of aggression in zoos

Unusual tumor cells may be overlooked factors in advanced breast cancer

[Press-News.org] Jaw dropping: scientists reveal how vertebrates came to have a faceSynchrotron X-rays provide new fossil evidence