(Press-News.org) JUPITER, FL, February 20, 2014 – The use of antibiotics is often considered among the most important advances in the treatment of human disease. Unfortunately, though, bacteria are finding ways to make a comeback. According to the Centers for Disease Control, more than two million people come down with antibiotic-resistant infections annually, and at least 23,000 die because their treatment can't stop the infection. In addition, the pipeline for new antibiotics has grown dangerously thin.

Now, a new study by scientists from the Florida campus of The Scripps Research Institute (TSRI) has uncovered a mechanism of drug resistance. This knowledge could have a major impact on the development of a pair of highly potent new antibiotic drug candidates.

"Now, because we know the resistance mechanism, we can design elements to minimize the emergence of resistance as these promising new drug candidates are developed," said Ben Shen, a TSRI professor who led the study, which was published February 20, 2014 online ahead of print by the Cell Press journal Chemistry & Biology.

Bacteria Versus Bacteria

The study centers around a kind of bacteria known as Streptomyces platensis, which protects itself from other bacteria by secreting anti-bacterial substances. Interestingly, Streptomyces platensis belongs to a large family of antibiotic-producing bacteria that accounts for more than two-thirds of naturally occurring clinically useful antibiotics.

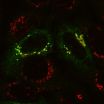

The antibiotic compounds secreted by Streptomyces platensis, which are called platensimycin and platencin and were discovered only recently, work by interfering with fatty acid synthesis. Fatty acid synthesis is essential for the production of bacterial cell walls and, consequently, the bacteria's existence. Platencin, although structurally similar to platensimycin, inhibits two separate enzymes in fatty acid synthesis instead of one.

The question remained, though, of why these compounds killed other bacteria, but not the producing bacteria Streptomyces platensis.

The Path to Resistance

The scientists set out to solve the mystery.

"Knowing how these bacteria protect themselves, what the mechanisms of self-resistance of the bacteria are, is important because they could transfer that resistance to other bacteria," said Tingting Huang, a research associate in the Shen laboratory who was first author of the study with Ryan M. Peterson of the University of Wisconsin, Madison.

Using genetic and bioinformatic techniques, the team identified two complementary mechanisms in the bacteria that confer resistance to platensimycin and platencin. In essence, the study found a pair of genes in Streptomyces platensis exploits a pathway to radically simplify fatty acid biosynthesis while bestowing an insensitivity to these particular antibiotics.

"Understanding how these elements work is a big leap forward," added Jeffrey D. Rudolf, a research associate in the Shen lab who worked on the study. "Now these bacteria have shown us how other bacteria might use this resistance mechanism to bypass fatty acid biosynthesis inhibition."

INFORMATION:

In addition to Shen, Huang, Peterson and Rudolf, the study, "Mechanisms of Self-Resistance in the Platensimycin and Platencin Producing Streptomyces Platensis MA7327 and MA7339 Strains," was authored by Michael J. Smanski of the University of Wisconsin, Madison.

The study was supported by the National Institutes of Health (Grant Numbers AI079070 and GM08505).

Scientists find resistance mechanism that could impact antibiotic drug development

2014-02-20

ELSE PRESS RELEASES FROM THIS DATE:

Chemical chaperones have helped proteins do their jobs for billions of years

2014-02-20

ANN ARBOR—An ancient chemical, present for billions of years, appears to have helped proteins function properly since time immemorial.

Proteins are the body's workhorses, and like horses they often work in teams. There exists a modern day team of multiple chaperone proteins that help other proteins fold into the complex 3D shapes they must achieve to function. This is necessary to avert many serious diseases caused when proteins misbehave.

But what happened before this team of chaperones was formed? How did the primordial cells that were the ancestors of modern life ...

Scientists discover 11 new genes affecting blood pressure

2014-02-20

New research from Queen Mary University of London has discovered 11 new DNA sequence variants in genes influencing high blood pressure and heart disease.

Identifying the new genes contributes to our growing understanding of the biology of blood pressure and, researchers believe, will eventually influence the development of new treatments. More immediately the study highlights opportunities to investigate the use of existing drugs for cardiovascular diseases.

The large international study, published today in the American Journal of Human Genetics, examined the DNA ...

A changing view of bone marrow cells

2014-02-20

In the battle against infection, immune cells are the body's offense and defense—some cells go on the attack while others block invading pathogens. It has long been known that a population of blood stem cells that resides in the bone marrow generates all of these immune cells. But most scientists have believed that blood stem cells participate in battles against infection in a delayed way, replenishing immune cells on the front line only after they become depleted.

Now, using a novel microfluidic technique, researchers at Caltech have shown that these stem cells might ...

Compound improves cardiac function in mice with genetic heart defect, MU study finds

2014-02-20

COLUMBIA, Mo. — Congenital heart disease is the most common form of birth defect, affecting one out of every 125 babies, according to the National Institutes of Health. Researchers from the University of Missouri recently found success using a drug to treat laboratory mice with one form of congenital heart disease, hypertrophic cardiomyopathy — a weakening of the heart caused by abnormally thick muscle. By suppressing a faulty protein, the researchers reduced the thickness of the mice's heart muscles and improved their cardiac functioning.

Maike Krenz, M.D., has been ...

Turning back the clock on aging muscles?

2014-02-20

A study co-published in Nature Medicine this week by University of Toronto researcher Penney Gilbert has determined a stem cell based method for restoring strength to damaged skeletal muscles of the elderly.

Skeletal muscles are some of the most important muscles in the body, supporting functions such as sitting, standing, blinking and swallowing. In aging individuals, the function of these muscles significantly decreases.

"You lose fifteen percent of muscle mass every single year after the age of 75, a trend that is irreversible," cites Gilbert, Assistant Professor ...

Researchers say distant quasars could close a loophole in quantum mechanics

2014-02-20

In a paper published this week in the journal Physical Review Letters, MIT researchers propose an experiment that may close the last major loophole of Bell's inequality — a 50-year-old theorem that, if violated by experiments, would mean that our universe is based not on the textbook laws of classical physics, but on the less-tangible probabilities of quantum mechanics.

Such a quantum view would allow for seemingly counterintuitive phenomena such as entanglement, in which the measurement of one particle instantly affects another, even if those entangled particles are ...

Crop species may be more vulnerable to climate change than we thought

2014-02-20

A new study by a Wits University scientist has overturned a long-standing hypothesis about plant speciation (the formation of new and distinct species in the course of evolution), suggesting that agricultural crops could be more vulnerable to climate change than was previously thought.

Unlike humans and most other animals, plants can tolerate multiple copies of their genes – in fact some plants, called polyploids, can have more than 50 duplicates of their genomes in every cell. Scientists used to think that these extra genomes helped polyploids survive in new and extreme ...

Surprising culprit found in cell recycling defect

2014-02-20

To remain healthy, the body's cells must properly manage their waste recycling centers. Problems with these compartments, known as lysosomes, lead to a number of debilitating and sometimes lethal conditions.

Reporting in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences (PNAS), researchers at Washington University School of Medicine in St. Louis have identified an unusual cause of the lysosomal storage disorder called mucolipidosis III, at least in a subset of patients. This rare disorder causes skeletal and heart abnormalities and can result in a shortened lifespan. ...

MD Anderson researcher uncovers some of the ancient mysteries of leprosy

2014-02-20

Research at The University of Texas MD Anderson Cancer Center is finally unearthing some of the ancient mysteries behind leprosy, also known as Hansen's disease, which has plagued mankind throughout history. The new research findings appear in the current edition of journal PLOS Neglected Tropical Diseases. According to this new hypothesis, the disease might be the oldest human-specific infection, with roots that likely stem back millions of years.

There are hundreds of thousands of new cases of leprosy worldwide each year, but the disease is rare in the United States, ...

Sustainable manufacturing system to better consider the human component

2014-02-20

CORVALLIS, Ore. – Engineers at Oregon State University have developed a new approach toward "sustainable manufacturing" that begins on the factory floor and tries to encompass the totality of manufacturing issues – including economic, environmental, and social impacts.

This approach, they say, builds on previous approaches that considered various facets of sustainability in a more individual manner. Past methods often worked backward from a finished product and rarely incorporated the complexity of human social concerns.

The findings have been published in the Journal ...