(Press-News.org) By attaching short sequences of single-stranded DNA to nanoscale building blocks, researchers can design structures that can effectively build themselves. The building blocks that are meant to connect have complementary DNA sequences on their surfaces, ensuring only the correct pieces bind together as they jostle into one another while suspended in a test tube.

Now, a University of Pennsylvania team has made a discovery with implications for all such self-assembled structures.

Earlier work assumed that the liquid medium in which these DNA-coated pieces float could be treated as a placid vacuum, but the Penn team has shown that fluid dynamics play a crucial role in the kind and quality of the structures that can be made in this way.

As the DNA-coated pieces rearrange themselves and bind, they create slipstreams into which other pieces can flow. This phenomenon makes some patterns within the structures more likely to form than others.

The research was conducted by professors Talid Sinno and John Crocker, alongside graduate students Ian Jenkins, Marie Casey and James McGinley, all of the Department of Chemical and Biomolecular Engineering in Penn's School of Engineering and Applied Science.

It was published in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences.

The Penn team's discovery started with an unusual observation about one of their previous studies, which dealt with a reconfigurable crystalline structure the team had made using DNA-coated plastic spheres, each 400 nanometers wide. These structures initially assemble into floppy crystals with square-shaped patterns, but, in a process similar to heat-treating steel, their patterns can be coaxed into more stable, triangular configurations.

Surprisingly, the structures they were making in the lab were better than the ones their computer simulations predicted would result. The simulated crystals were full of defects, places where the crystalline pattern of the spheres was disrupted, but the experimentally grown crystals were all perfectly aligned.

While these perfect crystals were a positive sign that the technique could be scaled up to build different kinds of structures, the fact that their simulations were evidently flawed indicated a major hurdle.

"What you see in an experiment," Sinno said, "is usually a dirtier version of what you see in simulation. We need to understand why these simulation tools aren't working if we're going to build useful things with this technology, and this result was evidence that we don't fully understand this system yet. It's not just a simulation detail that was missing; there's a fundamental physical mechanism that we're not including."

By process of elimination, the missing physical mechanism turned out to be hydrodynamic effects, essentially, the interplay between the particles and the fluid in which they are suspended while growing. The simulation of a system's hydrodynamics is critical when the fluid is flowing, such as how rocks are shaped by a rushing river, but has been considered irrelevant when the fluid is still, as it was in the researchers' experiments. While the particles' jostling perturbs the medium, the system remains in equilibrium, suggesting the overall effect is negligible.

"The conventional wisdom," Crocker said, "was that you don't need to consider hydrodynamic effects in these systems. Adding them to simulations is computationally expensive, and there are various kinds of proofs that these effects don't change the energy of the system. From there you can make a leap to saying, 'I don't need to worry about them at all.'"

Particle systems like ones made by these self-assembling DNA-coated spheres typically rearrange themselves until they reach the lowest energy state. An unusual feature of the researchers' system is that there are thousands of final configurations — most containing defects — that are just as energetically favorable as the perfect one they produced in the experiment.

"It's like you're in a room with a thousand doors," Crocker said. "Each of those doors takes you to a different structure, only one of which is the copper-gold pattern crystal we actually get. Without the hydrodynamics, the simulation is equally likely to send you through any one of those doors."

The researchers' breakthrough came when they realized that while hydrodynamic effects would not make any one final configuration more energy-favorable than another, the different ways particles would need to rearrange themselves to get to those states were not all equally easy. Critically, it is easier for a particle to make a certain rearrangement if it's following in the wake of another particle making the same moves.

"It's like slipstreaming," Crocker said. "The way the particles move together, it's like they're a school of fish."

"How you go determines what you get," Sinno said. "There are certain paths that have a lot more slipstreaming than others, and the paths that have a lot correspond to the final configurations we observed in the experiment."

The researchers believe that this finding will lay the foundation for future work with these DNA-coated building blocks, but the principle discovered in their study will likely hold up in other situations where microscopic particles are suspended in a liquid medium.

"If slipstreaming is important here, it's likely to be important in other particle assemblies," Sinno said. It's not just about these DNA-linked particles; it's about any system where you have particles at this size scale. To really understand what you get, you need to include the hydrodynamics."

INFORMATION:

The research was supported by the National Science Foundation through its Chemical, Bioengineering, Environmental and Transport Systems Division.

The motion of the medium matters for self-assembling particles, Penn research shows

2014-04-09

ELSE PRESS RELEASES FROM THIS DATE:

New climate pragmatism framework prioritizes energy access to drive innovation/development

2014-04-09

Drastically improved efforts to provide modern energy access to the poor opens up a new approach to development efforts and action on climate change, an international group of energy and environment scholars say in a new report, Our High-Energy Planet. The report is the first of three in the Climate Pragmatism project, a partnership of Arizona State University's Consortium for Science, Policy, and Outcomes (CSPO) and The Breakthrough Institute.

"Climate change can't be solved on the backs of the world's poorest people," said Daniel Sarewitz, a report coauthor and co-director ...

Vigilance for kidney problems key for rheumatoid arthritis patients

2014-04-09

Rochester, Minn. — Rheumatoid arthritis patients are likelier than the average person to develop chronic kidney disease, and more severe inflammation in the first year of rheumatoid arthritis, corticosteroid use, high blood pressure and obesity are among the risk factors, new Mayo Clinic research shows. Physicians should test rheumatoid arthritis patients periodically for signs of kidney problems, and patients should work to keep blood pressure under control, avoid a high-salt diet, and eliminate or scale back medications damaging to the kidneys, says senior author Eric ...

Researchers discover dangerous ways computer worms are spreading among smartphones

2014-04-09

VIDEO:

Professor Kevin Du and his team at Syracuse University have identified apps that could cause problems for smartphone users, allowing hackers easy access to sensitive information.

Click here for more information.

Professor Kevin Du and a team of researchers from the College of Engineering and Computer Science at Syracuse University have recently discovered that some of the most common activities among smartphone users—scanning 2D barcodes, finding free Wi-Fi access points, ...

Stanford scientists model a win-win situation: Growing crops on photovoltaic farms

2014-04-09

Growing agave and other carefully chosen plants amid photovoltaic panels could allow solar farms not only to collect sunlight for electricity but also to produce crops for biofuels, according to new computer models by Stanford scientists.

This co-location approach could prove especially useful in sunny, arid regions such as the southwestern United States where water is scarce, said Sujith Ravi, who is conducting postdoctoral research with professors David Lobell and Chris Field, both on faculty in environmental Earth system science and senior fellows at the Stanford Woods ...

Medication therapy management works for some but not all home health patients

2014-04-09

WEST LAFAYETTE, Ind. — Low-risk Medicare patients entering home health care who received medication therapy management by phone were three times less likely to be hospitalized within the next two months, while those at greater risk saw no benefit, according to a study led by Purdue University.

The study helped determine which patients benefit most from medication therapy management by phone and a way to identify them through a standardized risk score, said Alan Zillich, associate professor of pharmacy practice at Purdue, who led the research.

"Hopefully, this study ...

UC-led research finds chips with olestra cause body toxins to dip

2014-04-09

According to a clinical trial led by University of Cincinnati researchers, a snack food ingredient called olestra has been found to speed up the removal of toxins in the body.

Results are reported in the April edition of the Journal of Nutritional Biochemistry.

The trial demonstrated that olestra—a zero-calorie fat substitute found in low-calorie snack foods such as Pringles—could reduce the levels of serum polychlorinated biphenyls (PCBs) in people who had been exposed to PCBs.

High levels of PCBs in the body are associated with an increase in hypertension and diabetes. ...

Gusev Crater once held a lake after all, says ASU Mars scientist

2014-04-09

TEMPE, Ariz. - If desert mirages occur on Mars, "Lake Gusev" belongs among them. This come-and-go body of ancient water has come and gone more than once, at least in the eyes of Mars scientists.

Now, however, it's finally shifting into sharper focus, thanks to a new analysis of old data by a team led by Steve Ruff, associate research professor at Arizona State University's Mars Space Flight Facility in the School of Earth and Space Exploration. The team's report was just published in the April 2014 issue of the journal Geology.

The story begins in early 2004, when NASA ...

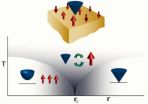

One kind of supersymmetry shown to emerge naturally

2014-04-09

UC Santa Barbara physicist Tarun Grover has provided definitive mathematical evidence for supersymmetry in a condensed matter system. Sought after in the realm of subatomic particles by physicists for several decades, supersymmetry describes a unique relationship between particles.

"As yet, no one has found supersymmetry in our universe, including at the Large Hadron Collider (LHC)," said the associate specialist at UCSB's Kavli Institute for Theoretical Physics (KITP). He is referring to the underground laboratory in Switzerland where the famous Higgs boson was identified ...

Violence intervention program effective in Vanderbilt pilot study

2014-04-09

Violent behavior and beliefs among middle school students can be reduced through the implementation of a targeted violence intervention program, according to a Vanderbilt study released in the Journal of Injury and Violence Research.

Manny Sethi, M.D., assistant professor of Orthopaedic Surgery and Rehabilitation, and his Vanderbilt co-authors evaluated 27 programs nationwide as part of a search for an appropriate school-based violence prevention program.

Their findings led to a single, evidence-based conflict resolution program that was evaluated in a pilot study of ...

Stanford scientists discover a novel way to make ethanol without corn or other plants

2014-04-09

Stanford University scientists have found a new, highly efficient way to produce liquid ethanol from carbon monoxide gas. This promising discovery could provide an eco-friendly alternative to conventional ethanol production from corn and other crops, say the scientists. Their results are published in the April 9 advanced online edition of the journal Nature.

"We have discovered the first metal catalyst that can produce appreciable amounts of ethanol from carbon monoxide at room temperature and pressure – a notoriously difficult electrochemical reaction," said Matthew ...