Puget Sound's rich waters supplied by deep, turbulent canyon

2014-04-14

(Press-News.org) The headwaters for Puget Sound's famously rich waters lie far below the surface, in a submarine canyon that draws nutrient-rich water up from the deep ocean. New measurements may explain how the Pacific Northwest's inland waters are able to support so many shellfish, salmon runs and even the occasional pod of whales.

University of Washington oceanographers made the first detailed measurements at the headwater's source, a submarine canyon offshore from the strait that separates the U.S. and Canada. Observations show water surging up through the canyon and mixing at surprisingly high rates, according to a paper published in March in Geophysical Research Letters.

"This is the headwaters of Puget Sound," said co-author Parker MacCready, a UW professor of oceanography. "That's why it's so salty in Puget Sound, that's why the water is pretty clean and that's why there's high productivity in Puget Sound, because you're constantly pulling in this deep water."

It has been known for decades that 20 to 30 times more deep water flows into Puget Sound than from all the rivers combined. Surface tides, while dramatic, play a minor role.

"The tidal currents that slosh the water back and forth, that's what's really obvious," MacCready said. "But there's also a slow, persistent circulation that is constantly bringing deep water in, mixing it up and sending the surface water out."

New measurements show this canyon potentially supplies most of the water coming into Puget Sound, the Strait of Juan de Fuca and Canada's Georgia Strait.

The intense flow and mixing measured inside the canyon could help explain the mysterious productivity of Northwest shores. Coastal winds usually bring nutrients up on the west coast, but the numbers don't add up for this region.

"Washington is several times more productive – has more phytoplankton – than Oregon or California, and yet the winds here are several times weaker. That's been kind of a puzzle, for years," said co-author Matthew Alford, an oceanographer with the UW's Applied Physics Laboratory.

The secret to the Northwest's outsize productivity could be marine canyons, an idea first suggested by UW oceanographer Barbara Hickey. The northern section of the west coast has many more canyons than Oregon or California, with 11 along the Washington coast.

The new paper provides the latest evidence for these canyons' importance. Measurements by another UW oceanographer in the 1970s first showed water flowing through Juan de Fuca Canyon with a direction that depends on the coastal winds. More recently, calculations by Hickey and a colleague in 2008 suggested submarine canyons could play an important role in supplying nutrients to the Northwest coastal waters.

Alford and MacCready measured inside the Juan de Fuca Canyon in April 2013 using an instrument, built at the UW Applied Physics Laboratory with funding from Washington Sea Grant, that takes water measurements near the seafloor. During a day and a half of round-the-clock observations they got lucky with the wind direction and recorded strong flow up through the canyon.

Water flowed as fast as 1.3 feet per second at 500 feet below the surface, and mixed at up to 1,000 times the normal rate for the deep ocean. The data also showed that the flow is hydraulically-controlled, meaning it flows smoothly over a shallow ridge just off the cape and then forms a turbulent breaking wave on the other side, mixing with the waters far above.

The deep water forced up through the canyon is rich in nutrients that support the growth of marine plants which then feed other marine life. Those waters also are more acidic and lower in oxygen, all of which contribute to water conditions in the Sound.

"The location of this sill would be an outstanding place to fish," Alford said. "People fish in Juan de Fuca Canyon pretty actively, and that's probably no coincidence."

Pinpointing the source of Puget Sound waters will help make better computer models of circulation through the region, and eventually could help forecast ocean acidity, harmful algal blooms and low-oxygen events.

"Canyons might be important not just for coastal productivity, but that mixed water also gets exported into the interior of the ocean," Alford said. "I look at this as a first step in getting canyons right in coastal models and in global climate models, because I think it could potentially be a very important source of mixing."

INFORMATION:

The research was funded by the Office of Naval Research and the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. Ship time aboard the Thomas G. Thompson was provided by the UW.

For more information, contact Alford at malford@apl.washington.edu or 206-221-3257 and MacCready at pmacc@uw.edu or 206-685-9588.

ELSE PRESS RELEASES FROM THIS DATE:

Study links domestic abuse to mental health problems in new mothers

2014-04-14

A new study shows that domestic abuse is closely linked to postpartum mental health problems, including depression and post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD), in mothers. The research also found that specific types of abuse are associated with specific mental health problems. The work was done by researchers at North Carolina State University, Simon Fraser University and the University of British Columbia.

"We wanted to see whether and how intimate partner abuse – physical, psychological and sexual – influenced postpartum mental health in women, including problems such ...

Neanderthals and Cro-magnons did not coincide on the Iberian Peninsula

2014-04-14

This news release is available in Spanish. Until now, the carbon 14 technique, a radioactive isotope which gradually disappears with the passing of time, has been used to date prehistoric remains. When about 40,000 years, in other words approximately the period corresponding to the arrival of the first humans in Europe, have elapsed, the portion that remains is so small that it can become easily contaminated and cause the dates to appear more recent. It was from 2005 onwards that a new technique began to be used; it is the one used to purify the collagen in DNA tests. ...

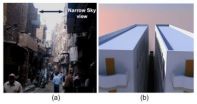

Let the sun shine in: Redirecting sunlight to urban alleyways

2014-04-14

WASHINGTON, April 14—In dense, urban centers around the world, many people live and work in dim and narrow streets surrounded by tall buildings that block sunlight. And as the global population continues to rise and buildings are jammed closer together, the darkness will only spread.

To alleviate the problem, Egyptian researchers have developed a corrugated, translucent panel that redirects sunlight onto narrow streets and alleyways. The panel is mounted on rooftops and hung over the edge at an angle, where it spreads sunlight onto the street below. The researchers describe ...

Wolves at the door: Study finds recent wolf-dog hybridization in Caucasus region

2014-04-14

Dog owners in the Caucasus Mountains of Georgia might want to consider penning up their dogs more often: hybridization of wolves with shepherd dogs might be more common, and more recent, than previously thought, according to a recently published study in the Journal of Heredity (DOI: 10.1093/jhered/esu014).

Dr. Natia Kopaliani, Dr. David Tarkhnishvili, and colleagues from the Institute of Ecology at Ilia State University in Georgia and from the Tbilisi Zoo in Georgia used a range of genetic techniques to extract and examine DNA taken from wolf and dog fur samples as well ...

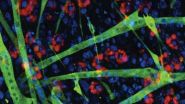

Regenerating muscle in Duchenne muscular dystrophy: Age matters

2014-04-14

LA JOLLA, Calif., April 11, 2014 — A team of scientists led by Pier Lorenzo Puri, M.D., associate professor at Sanford-Burnham Medical Research Institute (Sanford-Burnham), in collaboration with Fondazione Santa Lucia in Rome, Italy, have published details of how a class of drugs called "HDACis" drive muscle-cell regeneration in the early stages of dystrophic muscles, but fail to work in late stages. The findings are key to furthering clinical development of HDACis for Duchenne muscular dystrophy (DMD), an incurable muscle-wasting disease.

A symphony to rebuild muscle

The ...

New 'tunable' semiconductors will allow better detectors, solar cells

2014-04-14

One of the great problems in physics is the detection of electromagnetic radiation – that is, light – which lies outside the small range of wavelengths that the human eye can see. Think X-rays, for example, or radio waves.

Now, researchers have discovered a way to use existing semiconductors to detect a far wider range of light than is now possible, well into the infrared range. The team hopes to use the technology in detectors, obviously, but also in improved solar cells that could absorb infrared light as well as the sun's visible rays.

"This technology will also ...

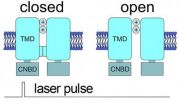

A stable model for an unstable target

2014-04-14

A study in The Journal of General Physiology provides new insights about singlet oxygen and sets the stage for better understanding of this highly reactive and challenging substance.

Singlet oxygen is an electronically excited state of oxygen that is less stable than normal oxygen. Its high reactivity has enabled its use in photodynamic therapy, in which light is used in combination with a photosensitizing drug to generate large amounts of singlet oxygen to kill cancer cells or various pathogens.

Light-generated singlet oxygen also plays a role in a range of biological ...

Better solar cells, better LED light and vast optical possibilities

2014-04-14

Changes at the atom level in nanowires offer vast possibilities for improvement of solar cells and LED light. NTNU-researchers have discovered that by tuning a small strain on single nanowires they can become more effective in LEDs and solar cells.

NTNU researchers Dheeraj Dasa and Helge Weman have, in cooperation with IBM, discovered that gallium arsenide can be tuned with a small strain to function efficiently as a single light-emitting diode or a photodetector. This is facilitated by the special hexagonal crystal structure, referred to as wurtzite, which the NTNU ...

Pioneering findings on the dual role of carbon dioxide in photosynthesis

2014-04-14

Scientists at Umeå University in Sweden have found that carbon dioxide, in its ionic form bicarbonate, has a regulating function in the splitting of water in photosynthesis. This means that carbon dioxide has an additional role to being reduced to sugar. The pioneering work is published in the latest issue of the scientific journal PNAS.

It is well known that inorganic carbon in the form of carbon dioxide, CO2, is reduced in a light driven process known as photosynthesis to organic compounds in the chloroplasts. Less well known is that inorganic carbon also affects the ...

The result of slow degradation

2014-04-14

This news release is available in German. Although persistent environmental pollutants have been and continue to be released worldwide, the Arctic and Antarctic regions are significantly more contaminated than elsewhere. The marine animals living there have some of the highest levels of persistent organic pollutant (POP) contamination of any creatures. The Inuit people of the Arctic, who rely on a diet of fish, seals and whales, have also been shown to have higher POP concentrations than people living in our latitudes.

Today, the production and use of nearly two dozen ...