(Press-News.org) VIDEO:

Wyss Institute Core Faculty member William Shih and Technology Development Fellow Steven Perrault explain why DNA nanodevices need protection inside the body and how a virus-inspired strategy helps protect them....

Click here for more information.

It's a familiar trope in science fiction: In enemy territory, activate your cloaking device. And real-world viruses use similar tactics to make themselves invisible to the immune system. Now scientists at Harvard's Wyss Institute for Biologically Inspired Engineering have mimicked these viral tactics to build the first DNA nanodevices that survive the body's immune defenses.

The results pave the way for smart DNA nanorobots that could use logic to diagnose cancer earlier and more accurately than doctors can today; target drugs to tumors, or even manufacture drugs on the spot to cripple cancer, the researchers report in the April 22 online issue of ACS Nano.

"We're mimicking virus functionality to eventually build therapeutics that specifically target cells," said Wyss Institute Core Faculty member William Shih, Ph.D., the paper's senior author. Shih is also an Associate Professor of Biological Chemistry and Molecular Pharmacology at Harvard Medical School and Associate Professor of Cancer Biology at the Dana-Farber Cancer Institute.

The same cloaking strategy could also be used to make artificial microscopic containers called protocells that could act as biosensors to detect pathogens in food or toxic chemicals in drinking water.

DNA is well known for carrying genetic information, but Shih and other bioengineers are using it instead as a building material. To do this, they use DNA origami -- a method Shih helped extend from 2D to 3D. In this method, scientists take a long strand of DNA and program it to fold into specific shapes, much as a single sheet of paper is folded to create various shapes in the traditional Japanese art.

Shih's team assembles these shapes to build DNA nanoscale devices that might one day be as complex as the molecular machinery found in cells. For example, they are developing methods to build DNA into tiny robots that sense their environment, calculate how to respond, then carry out a useful task, such as performing a chemical reaction or generating mechanical force or movement.

Such DNA nanorobots may themselves sound like science fiction, but they already exist. In 2012 Wyss Institute researchers reported in Science that they had built a nanorobot that uses logic to detect a target cell, then reveals an antibody that activates a "suicide switch" in leukemia or lymphoma cells.

For a DNA nanodevice to successfully diagnose or treat disease, it must survive the body's defenses long enough to do its job. But in their current study Shih's team discovered that DNA nanodevices injected into the bloodstream of mice are quickly digested.

"That led us to ask, 'How could we protect our particles from getting chewed up?'" Shih said.

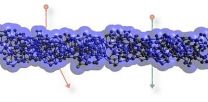

Nature inspired the solution. The scientists designed their nanodevices to mimic a type of virus that protects its genome by enclosing it in a solid protein case, then layering on an oily coating identical to that in membranes that surround living cells. That coating, or envelope, contains a double layer (bilayer) of phospholipid that helps the viruses evade the immune system and delivers them to the cell interior.

"We suspected that a virus-like envelope around our particles could solve our problem," Shih said.

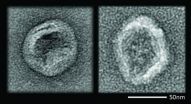

To coat DNA nanodevices with phospholipid, Steve Perrault, Ph.D., a Wyss Institute Technology Development fellow in Shih's group and the paper's lead author, first folded DNA into a virus-sized octahedron. Then, he took advantage of the precision-design capabilities of DNA nanotechnology, building in handles to hang lipids, which in turn directed the assembly of a single bilayer membrane surrounding the octahedron.

Under an electron microscope, the coated nanodevices closely resembled an enveloped virus.

Perrault then demonstrated that the new nanodevices survived in the body, by loading them with fluorescent dye, injecting them into mice, and using whole-body imaging to see what parts of the mouse glowed.

Just the bladder glowed in mice that received uncoated nanodevices, which meant that the animals broke them down quickly and were ready to excrete their contents. But the animals' entire body glowed for hours when they received the new, coated nanodevices. This showed that nanodevices remained in the bloodstream as long as effective drugs do.

The coated devices also evade the immune system. Levels of two immune-activating molecules were at least 100-fold lower in mice treated with coated nanodevices as opposed to uncoated nanodevices.

In the future, cloaked nanorobots could activate the immune system to fight cancer or suppress the immune system to help transplanted tissue become established.

"Activating the immune response could be useful clinically or something to avoid," Perrault said. "The main point is that we can control it."

"Patients with cancer and other diseases would benefit enormously from precise, molecular-scale tools to simultaneously diagnose and treat diseased tissues, and making DNA nanoparticles last in the body is a huge step in that direction," said Wyss Institute Founding Director Don Ingber, M.D., Ph.D.

INFORMATION:

This work was funded by the National Institutes of Health, the U.S. Army Research Laboratory's Army Research Office, and the Wyss Institute at Harvard University.

PRESS CONTACT

Wyss Institute for Biologically Inspired Engineering at Harvard University

Dan Ferber

dan.ferber@wyss.harvard.edu

+1 617-432-1547

IMAGES AND VIDEO AVAILABLE

About the Wyss Institute for Biologically Inspired Engineering at Harvard University

The Wyss Institute for Biologically Inspired Engineering at Harvard University uses Nature's design principles to develop bioinspired materials and devices that will transform medicine and create a more sustainable world. Working as an alliance among all of Harvard's Schools, and in partnership with Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center, Brigham and Women's Hospital, Boston Children's Hospital, Dana Farber Cancer Institute, Massachusetts General Hospital, the University of Massachusetts Medical School, Spaulding Rehabilitation Hospital, Boston University, Tufts University, and Charité - Universitätsmedizin Berlin, the Institute crosses disciplinary and institutional barriers to engage in high-risk research that leads to transformative technological breakthroughs. By emulating Nature's principles for self-organizing and self-regulating, Wyss researchers are developing innovative new engineering solutions for healthcare, energy, architecture, robotics, and manufacturing. These technologies are translated into commercial products and therapies through collaborations with clinical investigators, corporate alliances, and new start-ups.

Cloaked DNA nanodevices survive pilot mission

Successful foray opens door to virus-like DNA nanodevices that could diagnose diseased tissues and manufacture drugs to treat them

2014-04-22

ELSE PRESS RELEASES FROM THIS DATE:

Carnegie Mellon system lets iPad users explore data with their fingers

2014-04-22

PITTSBURGH—Spreadsheets may have been the original killer app for personal computers, but data tables don't play to the strengths of multi-touch devices such as tablets. So researchers at Carnegie Mellon University have developed a visualization approach that allows people to explore complex data with their fingers.

Called Kinetica, this proof-of-concept system for the Apple iPad converts tabular data, such as Excel spreadsheets, so that data points appear as colored spheres on the touchscreen. People can directly manipulate this data, using natural gestures to sort, ...

Child's autism risk accelerates with mother's age over 30

2014-04-22

PHILADELPHIA (April 22, 2014) – Older parents are more likely to have a child who develops an autism spectrum disorder (ASD) than are younger parents. A recent study from researchers from the Drexel University School of Public Health in Philadelphia and Karolinska Institute in Sweden provides more insight into how the risk associated with parental age varies between mothers' and fathers' ages, and found that the risk of having a child with both ASD and intellectual disability is larger for older parents.

In the study, published in the February 2014 issue of the International ...

Nanomaterial outsmarts ions

2014-04-22

Ions are an essential tool in chip manufacturing, but these electrically charged atoms can also be used to produce nano-sieves with homogeneously distributed pores. A particularly large number of electrons, however, must be removed from the atoms for this purpose. Such highly charged ions either lose a surprisingly large amount of energy or almost no energy at all as they pass through a membrane that measures merely one nanometer in thickness. Researchers from the Helmholtz-Zentrum Dresden-Rossendorf (HZDR) and Vienna University of Technology (TU Wien) report in the scientific ...

Gym culture likened to McDonalds

2014-04-22

Visit a typical gym and you will encounter a highly standardised notion of what the human body should look like and how much it should weigh. This strictly controlled body ideal is spread across the world by large actors in the fitness industry.

A new study explores how the fitness industry in many ways resembles that of fast food. One of the authors is from the University of Gothenburg.

McDonaldisation of the gym culture is the theme of an article published in Sports, Education and Society, where Thomas Johansson, professor at the University of Gothenburg, together ...

Two genes linked to inflammatory bowel disease

2014-04-22

CINCINNATI—Inflammatory Bowel Disease (IBD), a group of chronic inflammatory disorders of the intestine that result in painful and debilitating complications, affects over 1.4 million people in the U.S., and while there are treatments to reduce inflammation for patients, there is no cure.

Now, Cincinnati Cancer Center and University of Cincinnati (UC) Cancer Institute researcher Susan Waltz, PhD, and scientists in her lab have done what is believed to be the first direct genetic study to document the important function for the Ron receptor, a cell surface protein often ...

New design for mobile phone masts could cut carbon emissions

2014-04-22

A breakthrough in the design of signal amplifiers for mobile phone masts could deliver a massive 200MW cut in the load on UK power stations, reducing CO2 emissions by around 0.5 million tonnes a year.

Funded by the Engineering and Physical Sciences Research Council (EPSRC), the Universities of Bristol and Cardiff have designed an amplifier that works at 50 per cent efficiency compared with the 30 per cent now typically achieved.

Currently, a 40W transmitter in a phone mast's base station* requires just over 130W of power to amplify signals and send them wirelessly ...

Speed-reading apps may impair reading comprehension by limiting ability to backtrack

2014-04-22

To address the fact that many of us are on the go and pressed for time, app developers have devised speed-reading software that eliminates the time we supposedly waste by moving our eyes as we read. But don't throw away your books, papers, and e-readers just yet — research suggests that the eye movements we make during reading actually play a critical role in our ability to understand what we've just read.

The research is published in Psychological Science, a journal of the Association for Psychological Science.

"Our findings show that eye movements are a crucial part ...

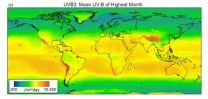

UV-radiation data to help ecological research

2014-04-22

Many research projects study the effects of temperature and precipitation on the global distribution of plant and animal species. However, an important component of climate research, the UV-B radiation, is often neglected. The landscape ecologists from UFZ in collaboration with their colleagues from the Universities in Olomouc (Czechia), Halle and Lüneburg have processed UV-B data from the U.S. NASA space agency in such a way that they can be used to study the influence of UV-B radiation on organisms.

The basic input data were provided by a NASA satellite that regularly, ...

A family of compact schemes with minimized dispersion and controllable dissipation was developed

2014-04-22

Spectral properties optimization is an important issue for developing schemes to resolve flow fields that are characterized by a wide range of length scales such as turbulent flows and aero acoustic phenomena. The work finished by Dr SUN Zhensheng and his ground provided a novel approach to optimize the dissipation and dispersion properties of a family of tri-diagonal compact schemes. The corresponding paper entitled "A high-resolution, hybrid compact-WENO scheme with minimized dispersion and controllable dissipation" was published in Sci China-Phys Mech Astron, 2014 Vol. ...

'Tween' television programming promotes some stereotypical conceptions of gender roles

2014-04-22

COLUMBIA, Mo. – The term "tween" denotes a child who is between the ages of 8 and 12 and is used to describe a preadolescent who is "in between" being a child and a teen. This demographic watches more television than any other age group and is considered to be a very lucrative market. Tween television programming consists of two genres: "teen scene" (geared toward girls) and "action-adventure" (geared toward boys). Researchers at the University of Missouri found that these programs could lead tweens to limit their views of their potential roles in society just as they begin ...

LAST 30 PRESS RELEASES:

Cal Poly’s fifth Climate Solutions Now conference to take place Feb. 23-27

Mask-wearing during COVID-19 linked to reduced air pollution–triggered heart attack risk in Japan

Achieving cross-coupling reactions of fatty amide reduction radicals via iridium-photorelay catalysis and other strategies

Shorter may be sweeter: Study finds 15-second health ads can curb junk food cravings

Family relationships identified in Stone Age graves on Gotland

Effectiveness of exercise to ease osteoarthritis symptoms likely minimal and transient

Cost of copper must rise double to meet basic copper needs

A gel for wounds that won’t heal

Iron, carbon, and the art of toxic cleanup

Organic soil amendments work together to help sandy soils hold water longer, study finds

Hidden carbon in mangrove soils may play a larger role in climate regulation than previously thought

Weight-loss wonder pills prompt scrutiny of key ingredient

Nonprofit leader Diane Dodge to receive 2026 Penn Nursing Renfield Foundation Award for Global Women’s Health

Maternal smoking during pregnancy may be linked to higher blood pressure in children, NIH study finds

New Lund model aims to shorten the path to life-saving cell and gene therapies

Researchers create ultra-stretchable, liquid-repellent materials via laser ablation

Combining AI with OCT shows potential for detecting lipid-rich plaques in coronary arteries

SeaCast revolutionizes Mediterranean Sea forecasting with AI-powered speed and accuracy

JMIR Publications’ JMIR Bioinformatics and Biotechnology invites submissions on Bridging Data, AI, and Innovation to Transform Health

Honey bees navigate more precisely than previously thought

Air pollution may directly contribute to Alzheimer’s disease

Study finds early imaging after pediatric UTIs may do more harm than good

UC San Diego Health joins national research for maternal-fetal care

New biomarker predicts chemotherapy response in triple-negative breast cancer

Treatment algorithms featured in Brain Trauma Foundation’s update of guidelines for care of patients with penetrating traumatic brain injury

Over 40% of musicians experience tinnitus; hearing loss and hyperacusis also significantly elevated

Artificial intelligence predicts colorectal cancer risk in ulcerative colitis patients

Mayo Clinic installs first magnetic nanoparticle hyperthermia system for cancer research in the US

Calibr-Skaggs and Kainomyx launch collaboration to pioneer novel malaria treatments

JAX-NYSCF Collaborative and GSK announce collaboration to advance translational models for neurodegenerative disease research

[Press-News.org] Cloaked DNA nanodevices survive pilot missionSuccessful foray opens door to virus-like DNA nanodevices that could diagnose diseased tissues and manufacture drugs to treat them