(Press-News.org) After cancer spreads, finding and destroying malignant cells that circulate in the body is usually critical to patient survival. Now, researchers reporting in the Cell Press journal Chemistry & Biology have developed a new method that allows investigators to label and track single tumor cells circulating in the blood. This advance could help investigators develop a better understanding of cancer spread and how to stop it.

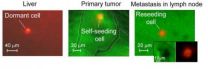

Cancer spread, or metastasis, leads to up to 90% of cancer deaths. Investigators currently do not have the clinical capability to intervene and stop the dissemination of tumor cells through metastasis because many steps of this process remain unclear. It is known that cancer cells undergo multiple steps, including invasion into nearby normal tissue, movement into the lymphatic system or the bloodstream, circulation to other parts of the body, invasion of new tissues, and growth at distant locations. Now, a new approach developed by Dr. Ekaterina Galanzha of the University of Arkansas for Medical Sciences in Little Rock and her colleagues allows for labeling and tracking of individual circulating cancer cells throughout the body, thereby helping researchers elucidate the pathways of single cells from start to finish.

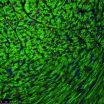

The advance uses photoswitchable fluorescent proteins that change their color in response to light. When the first laser of light hits the circulating tumor cells, they appear to be fluorescent green. A second laser, using a different wavelength, makes the cells appear to be fluorescent red. To label individual cells, researchers use a very thin violet laser beam aimed at small blood vessels.

The fluorescence from each cell is collected, detected, and reproduced on a computer monitor as real-time signal traces, allowing the investigators to count and track individual cells in the bloodstream

"This technology allows for the labeling of just one circulating pathological cell among billions of other normal blood cells by ultrafast changing color of photosensitive proteins inside the cell in response to laser light," explains Dr. Galanzha.

In tumor-bearing mice, the researchers could monitor the real-time dynamics of circulating cancer cells released from a primary tumor. They could also image the various final destinations of individual circulating cells and observe how these cells travel through circulation and colonize healthy tissue, existing sites of metastasis, or the site of the primary tumor. "Therefore, the approach may give oncologists knowledge on how to intervene and stop circulating cancer cell dissemination that might prevent the development of metastasis," she says.

The approach might also prove useful for other areas of medicine—for example, tracking bacteria during infections or immune-related cells during the development of autoimmune disease.

INFORMATION:

Chemistry & Biology, Nedosekin et al.: "In vivo photoswitchable flow cytometry for direct tracking of single circulating tumor cells."

New technology using florescent proteins tracks cancer cells circulating in the blood

2014-05-08

ELSE PRESS RELEASES FROM THIS DATE:

Spurt of heart muscle cell division seen in mice well after birth

2014-05-08

The entire heart muscle in young children may hold untapped potential for regeneration, new research suggests.

For decades, scientists believed that after a child's first few days of life, cardiac muscle cells did not divide. Instead, the assumption was that the heart could only grow by having the muscle cells become larger.

Cracks were already appearing in that theory. But new findings in mice, scheduled for publication in Cell, provide a dramatic counterexample -- with implications for the treatment of congenital heart disorders in humans.

Researchers at Emory University ...

Discovery that heart cells replicate during adolescence opens new avenue for heart repair

2014-05-08

It is widely accepted that heart muscle cells in mammals stop replicating shortly after birth, limiting the ability of the heart to repair itself after injury. A study published by Cell Press May 8th in the journal Cell now shows that heart muscle cells in mice undergo a brief proliferative burst prior to adolescence, increasing in number by about 40% to allow the heart to meet the increased circulatory needs of the body during a period of rapid growth. The findings suggest that thyroid hormone therapy could stimulate this process and enhance the heart's ability to regenerate ...

Polar bear genome reveals rapid adaptation to fatty diet

2014-05-08

Polar bears adapted to life in cold Arctic climates in part by relying on a high-fat diet mainly consisting of seals and their blubber. In a study published by Cell Press May 8th in the journal Cell, researchers discovered that mutations in genes involved in cardiovascular function allowed polar bears to rapidly evolve the ability to consume a fatty diet without developing high rates of heart disease. Moreover, the study revealed that polar bears diverged from brown bears less than 500,000 years ago—much more recently than estimates based on previous genomic data.

"In ...

Using genetics to measure the environmental impact of salmon farming

2014-05-08

Determining species diversity makes it possible to estimate the impact of human activity on marine ecosystems accurately. The environmental effects of salmon farming have been assessed, until now, by visually identifying the animals living in the marine sediment samples collected at specific distances from farming sites. A team led by Jan Pawlowski, professor at the Faculty of Science of the University of Geneva (UNIGE), Switzerland, analysed this type of sediment using a technique known as "DNA barcoding" that targets certain micro-organisms. Their research, which has ...

Humans may benefit from new insights into polar bear's adaptation to high-fat diet

2014-05-08

A comparison of the genomes of polar bears and brown bears reveals that the polar bear is a much younger species than previously believed, having diverged from brown bears less than 500,000 years ago.

The analysis also uncovered several genes that may be involved in the polar bears' extreme adaptations to life in the high Arctic. The species lives much of its life on sea ice, where it subsists on a blubber-rich diet of primarily marine mammals.

The genes pinpointed by the study are related to fatty acid metabolism and cardiovascular function, and may explain the bear's ...

Better cognition seen with gene variant carried by 1 in 5

2014-05-08

A scientific team led by the Gladstone Institutes and UC San Francisco has discovered that a common form of a gene already associated with long life also improves learning and memory, a finding that could have implications for treating age-related diseases like Alzheimer's.

The researchers found that people who carry a single copy of the KL-VS variant of the KLOTHO gene perform better on a wide variety of cognitive tests. When the researchers modeled the effects in mice, they found it strengthened the connections between neurons that make learning possible – what is known ...

Penn yeast study identifies novel longevity pathway

2014-05-08

PHILADELPHIA - Ancient philosophers looked to alchemy for clues to life everlasting. Today, researchers look to their yeast. These single-celled microbes have long served as model systems for the puzzle that is the aging process, and in this week's issue of Cell Metabolism, they fill in yet another piece.

The study, led by researchers at the University of Pennsylvania, identifies a new molecular circuit that controls longevity in yeast and more complex organisms and suggests a therapeutic intervention that could mimic the lifespan-enhancing effect of caloric restriction, ...

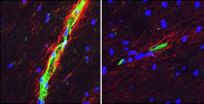

Study helps explain why MS is more common in women

2014-05-08

A newly identified difference between the brains of women and men with multiple sclerosis (MS) may help explain why so many more women than men get the disease, researchers at Washington University School of Medicine in St. Louis report.

In recent years, the diagnosis of MS has increased more rapidly among women, who get the disorder nearly four times more than men. The reasons are unclear, but the new study is the first to associate a sex difference in the brain with MS.

The findings appear May 8 in The Journal of Clinical Investigation.

Studying mice and people, ...

Immune cells found to fuel colon cancer stem cells

2014-05-08

ANN ARBOR, Mich. — A subset of immune cells directly target colon cancers, rather than the immune system, giving the cells the aggressive properties of cancer stem cells.

So finds a new study that is an international collaboration among researchers from the United States, China and Poland.

"If you want to control cancer stem cells through new therapies, then you need to understand what controls the cancer stem cells," says senior study author Weiping Zou, M.D., Ph.D., Charles B. de Nancrede Professor of surgery, immunology and biology at the University of Michigan Medical ...

What doesn't kill you may make you live longer

2014-05-08

What is the secret to aging more slowly and living longer? Not antioxidants, apparently.

Many people believe that free radicals, the sometimes-toxic molecules produced by our bodies as we process oxygen, are the culprit behind aging. Yet a number of studies in recent years have produced evidence that the opposite may be true.

Now, researchers at McGill University have taken this finding a step further by showing how free radicals promote longevity in an experimental model organism, the roundworm C. elegans. Surprisingly, the team discovered that free radicals – also ...