(Press-News.org) HOUSTON -- (May 15, 2014) -- A first-of-its-kind study this week suggests that the genomes of new species may evolve in a similar, repeatable fashion -- even in cases where populations are evolving in parallel at separate locations. The research is featured on the cover of the May 16 issue of Science.

A team of evolutionary biologists at Rice University, the University of Sheffield and eight other universities used a combination of ecological fieldwork and genomic assays to see how natural selection is playing out across the genome of a Southern California stick insect that is in the process of evolving into two unique species.

"Speciation is the evolutionary process that gives rise to new species, and it occurs when barriers prevent two groups of populations from exchanging genes," said Rice co-author Scott Egan. "One way to study how speciation occurs is to look for examples where partial reproductive barriers exist but where genes are still exchanged."

The stick insect Timema cristinae is one such example. Timema are closely related to "walking sticks," plant-eating insects that look like twigs. Timema's shape and color act as natural camouflage and help them avoid being eaten by predators, such as birds. More than a dozen unique species of Timema have evolved to feed on specific plants in California and northern Mexico.

One of these, T. cristinae, is found in two distinct varieties. One variety, or ecotype, feeds on the thin, needle-like leaves of a shrub called Adenastoma and features a distinct white stripe on its back that serves as camouflage. The other ecotype has no stripe and feeds on Ceanothus, a plant with wide green leaves where the stripe would stand out.

"Populations of T. cristinae on the two host plants have evolved many differences in their physical form while still exchanging genes," said Egan, a Huxley Faculty Fellow in Ecology and Evolutionary Biology at Rice. "These same populations have also evolved barriers to gene flow. We call this process 'speciation with gene flow,' and evolutionary biologists have long wondered if the genetic basis for this process is highly repeatable and if the genes involved are spread out across the whole genome or in a few discrete regions."

To find out whether this was the case, Egan and a dozen co-authors led by University of Sheffield biologist Patrik Nosil conducted four years of detailed genomic and ecological tests. They first had to sequence the genome for T. cristinae and identify which portions of the genome corresponded to particular biological functions. They then collected about 160 T. cristinae from the wild. Samples were collected at several geographic locations and were equally split between the ecotypes on the two host plants.

"We resequenced the genome of each individual that we collected and looked at which genes were differentiated between populations adapted to different host plants," Nosil said. "Because we also conducted an experiment in the field measuring evolution in real time, we gained information on how natural selection is pulling these populations apart."

For example, the team found that many of the genetic differences were reated to the biochemical function of metal ion binding, and metals are known to influence differences in pigmentation and mandible shape between the two T. cristinae ecotypes.

Previous ecological studies have shown that Timema do not migrate long distances. Because of this, the team expected to find evidence of localized gene flow among individuals collected at specific geographic locations. The genomic tests confirmed this, but they also revealed a pattern in the way that natural selection was playing out at each of the localities.

"In particular, we found that there were regions of the genome that exhibited significant differences between populations from host plant 1 and host plant 2, regardless of where the individuals were collected," Nosil said.

That suggested that evolution might be occurring in the same repeatable fashion at each location. To further test this, the team devised an experiment to gather genomic data from individuals that were actively under selection.

"We took individuals from a mixed population of the striped versus the no-striped ecotype, and we transplanted them back into nature onto the two host plants in five different sets," Egan said. "We allowed them to go an entire generation, and then we resampled those populations, resequenced the genome of the survivors and compared those to the ancestors that we started with a year before. We tried to match up the allele frequency shifts in this experiment with the genome-level differentiation that we observed in our genome-resequencing populations. And what we found was that many of the regions that were highly differentiated in nature were the exact same regions that were responding to our selection experiment."

Egan said it was previously impossible to conduct this kind of study because of the expense of genomic tests. Though the genomes of many plant, animal and microbial species have been sequenced over the past decade, most of those are model organisms. Scientists use model organisms to study critical biological processes, but Egan said the study of nonmodel organisms is often the key to ecological questions, including those related to how the environment influences natural selection and speciation.

"The world of genomics is beginning to open up for people like me who don't study model organisms," Egan said. "This is allowing us to address, in new ways, questions that Darwin posed over 150 years ago."

INFORMATION:

Study co-authors include Víctor Soria-Corrasco, Aaron Comeault and Timothy Farkas, all of the University of Sheffield; Zachariah Gompert of Utah State University; Thomas Parchman of the University of Nevada, Reno; Spencer Johnston of Texas A&M University; Alex Buerkle of the University of Wyoming; Jeffrey Feder of the University of Notre Dame; Jens Bast of the University of Göttingen, Germany; Tanja Schwander of the University of Lausanne, Switzerland; and Bernard Crespi of Simon Fraser University, Canada. The research was supported by the European Research Council, Utah State University and the Wellcome Trust Centre for Human Genetics.

High-resolution images are available for download at:

http://news.rice.edu/wp-content/uploads/2014/05/0515_STICK-Timema-orig.jpg

CAPTION: Researchers used a combination of ecological fieldwork and genomic assays to see how natural selection is playing out across the genome of Timema cristinae, a California stick insect that is evolving into two unique species.

CREDIT: M. Muschick/University of Sheffield

http://news.rice.edu/wp-content/uploads/2014/05/0515_STICK-diagram-lg.jpg

CAPTION: The species Timema cristinae has two distinct varieties, or ecotypes. One features a distinct white stripe on its back and feeds on the thin, needle-like leaves of a shrub called Adenastoma. The other phenotype has no stripe and feeds on Ceanothus.

CREDIT: T. Farkas/University of Sheffield

http://news.rice.edu/wp-content/uploads/2014/05/0515_STICK-Tim-lg.jpg

CAPTION: University of Sheffield graduate student Timothy Farkas collects a Timema specimen.

CREDIT: P. Nosil/University of Sheffield

http://news.rice.edu/wp-content/uploads/2014/05/0515_STICK-Timema2-lg.jpg

CAPTION: Timema cristinae

CREDIT: A. Comeault/University of Sheffield

http://news.rice.edu/wp-content/uploads/2014/05/0515_STICK-Egan-lg.jpg

CAPTION: Scott Egan

CREDIT: S. Egan/Rice University

Located on a 300-acre forested campus in Houston, Rice University is consistently ranked among the nation's top 20 universities by U.S. News & World Report. Rice has highly respected schools of Architecture, Business, Continuing Studies, Engineering, Humanities, Music, Natural Sciences and Social Sciences and is home to the Baker Institute for Public Policy. With 3,920 undergraduates and 2,567 graduate students, Rice's undergraduate student-to-faculty ratio is 6.3-to-1. Its residential college system builds close-knit communities and lifelong friendships, just one reason why Rice has been ranked No. 1 for best quality of life multiple times by the Princeton Review and No. 2 for "best value" among private universities by Kiplinger's Personal Finance.

Caught in the act: Study probes evolution of California insect

First-of-its-kind study reveals parallel genomic changes during species formation

2014-05-15

ELSE PRESS RELEASES FROM THIS DATE:

Marijuana use involved in more fatal accidents in Colorado

2014-05-15

AURORA, Colo. (May 15, 2014) – The proportion of marijuana-positive drivers involved in fatal motor vehicle crashes in Colorado has increased dramatically since the commercialization of medical marijuana in the middle of 2009, according to a study by University of Colorado School of Medicine researchers.

With data from the National Highway Traffic Safety Administration's Fatality Analysis Reporting System covering 1994 to 2011, the researchers analyzed fatal motor vehicle crashes in Colorado and in the 34 states that did not have medical marijuana laws, comparing changes ...

'Physician partners' free doctors to focus on patients, not paperwork

2014-05-15

Primary care physicians already have enough administrative duties on their plates, and the implementation of electronic medical records has only added to their burden. As a result, they have less time to spend with their patients.

But a new UCLA study suggests a simple way to lighten their load: a "physician partner" whose role would be to work on those administrative tasks, such as entering information into patient records, that take up so much of doctors' time. A physician partner allows doctors to focus more of their attention on their patients and leads to greater ...

Negative stereotypes can cancel each other out on resumes

2014-05-15

Stereotypes of gay men as effeminate and weak and black men as threatening and aggressive can hurt members of those groups when white people evaluate them in employment, education, criminal justice and other contexts.

But the negative attributes of the two stereotypes can cancel one another out for gay black men in the employment context, according to research by a Princeton University graduate student in sociology, challenging the commonly held idea that membership in multiple marginalized groups leads to more discrimination than being a member of a single such group.

Sociologist ...

Penn Vet study reveals Salmonella's hideout strategy

2014-05-15

The body's innate immune system is a first line of defense, intent on sensing invading pathogens and wiping them out before they can cause harm. It should not be surprising then that bacteria have evolved many ways to specifically evade and overcome this sentry system in order to spread infection.

A study led by researchers in the University of Pennsylvania's School of Veterinary Medicine now reveals how some Salmonella bacteria hide from the immune system, allowing them to persist and cause systemic infection. The findings could help researchers craft a more effective ...

Research finds human impact may cause Sierra Nevada to rise, increase seismicity of San Andreas Fault

2014-05-15

RENO, Nev. – Like a detective story with twists and turns in the plot, scientists at the University of Nevada, Reno are unfolding a story about the rapid uplift of the famous 400-mile long Sierra Nevada mountain range of California and Nevada.

The newest chapter of the research is being published today in the scientific journal Nature, showing that draining of the aquifer for agricultural irrigation in California's Central Valley results in upward flexing of the earth's surface and the surrounding mountains due to the loss of mass within the valley. The groundwater subsidence ...

A skeleton clue to early American ancestry

2014-05-15

This news release is available in Spanish and Arabic.

The discovery of a near-complete human skeleton in a watery cave in Mexico is helping scientists answer the question, "Who were the first Americans?" The finding, reported in the 16 May issue of the journal Science, sheds new light on a decades-long debate among archaeologists and anthropologists.

Deciphering the ancestry of the first people to populate the Americas has been a challenge.

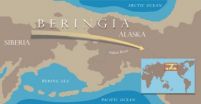

On the basis of genetics, modern Native Americans are thought to descend from Siberians who moved into eastern Beringia (the ...

Oldest most complete, genetically intact human skeleton in New World

2014-05-15

WASHINGTON (May 15, 2014)—The skeletal remains of a teenage female from the late Pleistocene or last ice age found in an underwater cave in Mexico have major implications for our understanding of the origins of the Western Hemisphere's first people and their relationship to contemporary Native Americans.

In a paper released today in the journal Science, an international team of researchers and cave divers present the results of an expedition that discovered a near-complete early American human skeleton with an intact cranium and preserved DNA. The remains were found surrounded ...

WSU anthropologist leads genetic study of prehistoric girl

2014-05-15

PULLMAN, Wash.—For more than a decade, Washington State University molecular anthropologist Brian Kemp has teased out the ancient DNA of goose and salmon bones from Alaska, human remains from North and South America, and human coprolites—ancient poop—from Oregon and the American Southwest.

His aim: use genetics as yet another archaeological record offering clues to the identities of ancient people and how they lived and moved across the landscape.

As head of the team studying the DNA of Naia, an adolescent girl who fell into a Yucatan sinkhole some 12,000 years ago, he ...

Genetic study helps resolve years of speculation about first people in the Americas

2014-05-15

CHAMPAIGN, Ill. — A new study could help resolve a longstanding debate about the origins of the first people to inhabit the Americas, researchers report in the journal Science. The study relies on genetic information extracted from the tooth of an adolescent girl who fell into a sinkhole in the Yucatan 12,000 to 13,000 years ago.

The girl's remains were found alongside those of ancient extinct beasts that also fell into the "inescapable natural trap," as researchers described the sinkhole. The team used radiocarbon dating and analyzed chemical signatures in bones and ...

Dating and DNA show Paleoamerican-Native American connection

2014-05-15

Eastern Asia, Western Asia, Japan, Beringia and even Europe have all been suggested origination points for the earliest humans to enter the Americas because of apparent differences in cranial form between today's Native Americans and the earliest known Paleoamerican skeletons. Now an international team of researchers has identified a nearly complete Paleoamerican skeleton with Native American DNA that dates close to the time that people first entered the New World.

"Individuals from 9,000 or more years ago have morphological attributes -- physical form and structure -- ...

LAST 30 PRESS RELEASES:

The hidden breath of cities: Why we need to look closer at public fountains

Rewetting peatlands could unlock more effective carbon removal using biochar

Microplastics discovered in prostate tumors

ACES marks 150 years of the Morrow Plots, our nation's oldest research field

Physicists open door to future, hyper-efficient ‘orbitronic’ devices

$80 million supports research into exceptional longevity

Why the planet doesn’t dry out together: scientists solve a global climate puzzle

Global greening: The Earth’s green wave is shifting

You don't need to be very altruistic to stop an epidemic

Signs on Stone Age objects: Precursor to written language dates back 40,000 years

MIT study reveals climatic fingerprints of wildfires and volcanic eruptions

A shift from the sandlot to the travel team for youth sports

Hair-width LEDs could replace lasers

The hidden infections that refuse to go away: how household practices can stop deadly diseases

Ochsner MD Anderson uses groundbreaking TIL therapy to treat advanced melanoma in adults

A heatshield for ‘never-wet’ surfaces: Rice engineering team repels even near-boiling water with low-cost, scalable coating

Skills from being a birder may change—and benefit—your brain

Waterloo researchers turning plastic waste into vinegar

Measuring the expansion of the universe with cosmic fireworks

How horses whinny: Whistling while singing

US newborn hepatitis B virus vaccination rates

When influencers raise a glass, young viewers want to join them

Exposure to alcohol-related social media content and desire to drink among young adults

Access to dialysis facilities in socioeconomically advantaged and disadvantaged communities

Dietary patterns and indicators of cognitive function

New study shows dry powder inhalers can improve patient outcomes and lower environmental impact

Plant hormone therapy could improve global food security

A new Johns Hopkins Medicine study finds sex and menopause-based differences in presentation of early Lyme disease

Students run ‘bee hotels’ across Canada - DNA reveals who’s checking in

SwRI grows capacity to support manufacture of antidotes to combat nerve agent, pesticide exposure in the U.S.

[Press-News.org] Caught in the act: Study probes evolution of California insectFirst-of-its-kind study reveals parallel genomic changes during species formation