(Press-News.org) Images taken by Rice University scientists show that some diamonds are not forever.

The Rice researchers behind a new study that explains the creation of nanodiamonds in treated coal also show that some microscopic diamonds only last seconds before fading back into less-structured forms of carbon under the impact of an electron beam.

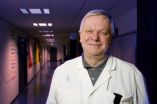

The research by Rice chemist Ed Billups and his colleagues appears in the American Chemical Society's Journal of Physical Chemistry Letters.

Billups and Yanqiu Sun, a former postdoctoral researcher in his lab, witnessed the interesting effect while working on ways to chemically reduce carbon from anthracite coal and make it soluble. First they noticed nanodiamonds forming amid the amorphous, hydrogen-infused layers of graphite.

It happened, they discovered, when they took close-ups of the coal with an electron microscope, which fires an electron beam at the point of interest. Unexpectedly, the energy input congealed clusters of hydrogenated carbon atoms, some of which took on the lattice-like structure of nanodiamonds.

"The beam is very powerful," Billups said. "To knock hydrogen atoms off of something takes a tremendous amount of energy."

Even without the kind of pressure needed to make macroscale diamonds, the energy knocked loose hydrogen atoms to prompt a chain reaction between layers of graphite in the coal that resulted in diamonds between 2 and 10 nanometers wide.

But the most "nano" of the nanodiamonds were seen to fade away under the power of the electron beam in a succession of images taken over 30 seconds.

"The small diamonds are not stable and they revert to the starting material, the anthracite," Billups said.

Billups turned to Rice theoretical physicist Boris Yakobson and his colleagues at the Technological Institute for Superhard and Novel Carbon Materials in Moscow to explain what the chemists saw. Yakobson, Pavel Sorokin and Alexander Kvashnin had already come up with a chart -- called a phase diagram -- that demonstrated how thin diamond films might be made without massive pressure.

They used similar calculations to show how nanodiamonds could form in treated anthracite and subbituminous coal. In this case, the electron microscope's beam knocks hydrogen atoms loose from carbon layers. Then the dangling bonds compensate by connecting to an adjacent carbon layer, which is prompted to connect to the next layer. The reaction zips the atoms into a matrix characteristic of diamond until pressure forces the process to halt.

Natural, macroscale diamonds require extreme pressures and temperatures to form, but the phase diagram should be reconsidered for nanodiamonds, the researchers said.

"There is a window of stability for diamonds within the range of 19-52 angstroms (tenths of a nanometer), beyond which graphite is more stable," Billups said. Stable nanodiamonds up to 20 nanometers in size can be formed in hydrogenated anthracite, they found, though the smallest nanodiamonds were unstable under continued electron-beam radiation.

Billups noted subsequent electron-beam experiments with pristine anthracite formed no diamonds, while tests with less-robust infusions of hydrogen led to regions with "onion-like fringes" of graphitic carbon, but no fully formed diamonds. Both experiments lent support to the need for sufficient hydrogen to form nanodiamonds.

Kvashnin is a former visiting student at Rice and a graduate student at the Moscow Institute of Physics and Technology (MIPT). Sorokin holds appointments at MIPT and the National University of Science and Technology, Moscow. Yakobson is Rice's Karl F. Hasselmann Professor of Mechanical Engineering and Materials Science, a professor of chemistry and a member of the Richard E. Smalley Institute for Nanoscale Science and Technology. Billups is a professor of chemistry at Rice.

INFORMATION:

The Robert A. Welch Foundation, the Ministry of Education and Science of the Russian Federation and the Russian Foundation for Basic Research supported the research.

Read the abstract at http://pubs.acs.org/doi/abs/10.1021/jz5007912

Follow Rice News and Media Relations via Twitter @RiceUNews

Related Materials:

Ed Billups Research Group: http://billups.rice.edu/research/

Yakobson Research Group: http://biygroup.blogs.rice.edu

Sorokin Group: http://tisnum.ru/research-departments/theoretical-group_eng.html

Images for download:

http://news.rice.edu/wp-content/uploads/2014/05/0527_DIAMOND-1-WEB-horizontal.jpg

http://news.rice.edu/wp-content/uploads/2014/05/0527_DIAMOND-1-WEB-VERTICAL.jpg

A series of images shows a small nanodiamond (the dark spot in the lower right corner) reverting to anthracite. Rice University scientists saw nanodiamonds form in hydrogenated coal when hit by the electron beam used in high-resolution transmission electron microscopes. But smaller diamonds like this one degraded with subsequent images. The scale bar is 1 nanometer. (Credit: Billups Lab/Rice University)

http://news.rice.edu/wp-content/uploads/2014/05/0527_DIAMOND-2-WEB.jpg

The dark spots in these images are nanodiamonds formed in hydrogenated anthracite coal when hit by beams from an electron microscope, according to researchers at Rice University. (Credit: Billups Lab/Rice University)

Located on a 300-acre forested campus in Houston, Rice University is consistently ranked among the nation's top 20 universities by U.S. News & World Report. Rice has highly respected schools of Architecture, Business, Continuing Studies, Engineering, Humanities, Music, Natural Sciences and Social Sciences and is home to the Baker Institute for Public Policy. With 3,920 undergraduates and 2,567 graduate students, Rice's undergraduate student-to-faculty ratio is 6.3-to-1. Its residential college system builds close-knit communities and lifelong friendships, just one reason why Rice has been ranked No. 1 for best quality of life multiple times by the Princeton Review and No. 2 for "best value" among private universities by Kiplinger's Personal Finance.

Not all diamonds are forever

Rice University researchers see nanodiamonds created in coal fade away in seconds

2014-05-22

ELSE PRESS RELEASES FROM THIS DATE:

EuroPCR 2014 examines vascular response and long-term safety of bioresorbable scaffolds

2014-05-22

22 May 2014, Paris, France: At EuroPCR 2014 yesterday, experts discussed the development in evidence for bioresorbable vascular scaffolds, which represent an era of vascular restoration in interventional cardiology. The available data were analysed and participants heard that bioresorbable fixed strut vascular scaffolds are associated with increased acute thrombogenicity due to flow disturbances. This means that patients who are implanted with these devices need to receive ongoing dual antiplatelet therapy. The panellists also pointed out that endothelialisation is further ...

RaDAR guides proteins into the nucleus

2014-05-22

May 22, 2014, New York, NY – A Ludwig Cancer Research study has identified a novel pathway by which proteins are actively and specifically shuttled into the nucleus of a cell. Published online today in Cell, the finding captures a precise molecular barcode that flags proteins for such import and describes the biochemical interaction that drives this critically important process. The discovery could help illuminate the molecular dysfunction that underpins a broad array of ailments, ranging from autoimmune diseases to cancers.

Although small proteins can diffuse passively ...

Wondering about the state of the environment? Just eavesdrop on the bees

2014-05-22

VIDEO:

This shows bees on dandelions.

Click here for more information.

Researchers have devised a simple way to monitor wide swaths of the landscape without breaking a sweat: by listening in on the "conversations" honeybees have with each other. The scientists' analyses of honeybee waggle dances reported in the Cell Press journal Current Biology on May 22 suggest that costly measures to set aside agricultural lands and let the wildflowers grow can be very beneficial to bees.

"In ...

Blocking pain receptors found to extend lifespan in mammals

2014-05-22

Chronic pain in humans is associated with worse health and a shorter lifespan, but the molecular mechanisms underlying these clinical observations have not been clear. A study published by Cell Press May 22nd in the journal Cell reveals that the activity of a pain receptor called TRPV1 regulates lifespan and metabolic health in mice. The study suggests that pain perception can affect the aging process and reveals novel strategies that could improve metabolic health and longevity in humans.

"The TRPV1 receptor is a major drug target with many known drugs in the clinic ...

Genes discovered linking circadian clock with eating schedule

2014-05-22

LA JOLLA—For most people, the urge to eat a meal or snack comes at a few, predictable times during the waking part of the day. But for those with a rare syndrome, hunger comes at unwanted hours, interrupts sleep and causes overeating.

Now, Salk scientists have discovered a pair of genes that normally keeps eating schedules in sync with daily sleep rhythms, and, when mutated, may play a role in so-called night eating syndrome. In mice with mutations in one of the genes, eating patterns are shifted, leading to unusual mealtimes and weight gain. The results were published ...

New technology may help identify safe alternatives to BPA

2014-05-22

Numerous studies have linked exposure to bisphenol A (BPA) in plastic, receipt paper, toys, and other products with various health problems from poor growth to cancer, and the FDA has been supporting efforts to find and use alternatives. But are these alternatives safer? Researchers reporting in the Cell Press journal Chemistry & Biology have developed new tests that can classify such compounds' activity with great detail and speed. The advance could offer a fast and cost-effective way to identify safe replacements for BPA.

Millions of tons of BPA and related compounds ...

Discovery of how Taxol works could lead to better anticancer drugs

2014-05-22

VIDEO:

This video shows how the constant addition of tubulin bound to GTP provides a cap that prevents the microtubule from falling apart. UC Berkeley scientists found that the hydrolyzation of...

Click here for more information.

University of California, Berkeley, scientists have discovered the extremely subtle effect that the prescription drug Taxol has inside cells that makes it one of the most widely used anticancer agents in the world.

The details, involving the drug's ...

Gene behind unhealthy adipose tissue identified

2014-05-22

Researchers at Karolinska Institutet in Sweden have for the first time identified a gene driving the development of pernicious adipose tissue in humans. The findings imply, which are published in the scientific journal Cell Metabolism, that the gene may constitute a risk factor promoting the development of insulin resistance and type 2 diabetes.

Adipose tissue can expand in two ways: by increasing the size and/or the number of the fat cells. It is well established that subjects with few but large fat cells, so-called hypertrophy, display an increased risk of developing ...

Computer models helping unravel the science of life?

2014-05-22

Scientists have developed a sophisticated computer modelling simulation to explore how cells of the fruit fly react to changes in the environment.

The research, published today in the science journal Cell, is part of an on-going study at The Universities of Manchester and Sheffield that is investigating how external environmental factors impact on health and disease.

The model shows how cells of the fruit fly communicate with each other during its development. Dr Martin Baron, who led the research, said: "The work is a really nice example of researchers from different ...

Supportive tissue in tumors hinders, rather than helps, pancreatic cancer

2014-05-22

HOUSTON – Fibrous tissue long suspected of making pancreatic cancer worse actually supports an immune attack that slows tumor progression but cannot overcome it, scientists at The University of Texas MD Anderson Cancer Center report in the journal Cancer Cell.

"This supportive tissue that's abundant in pancreatic cancer tumors is not a traitor as we thought but rather an ally that is fighting to the end. It's a losing battle with cancer cells, but progression is much faster without their constant resistance," said study senior author Raghu Kalluri, Ph.D., M.D., chair ...

LAST 30 PRESS RELEASES:

Roadmap for Europe’s biodiversity monitoring system

Novel camel antimicrobial peptides show promise against drug-resistant bacteria

Scientists discover why we know when to stop scratching an itch

A hidden reason inner ear cells die – and what it means for preventing hearing loss

Researchers discover how tuberculosis bacteria use a “stealth” mechanism to evade the immune system

New microscopy technique lets scientists see cells in unprecedented detail and color

Sometimes less is more: Scientists rethink how to pack medicine into tiny delivery capsules

Scientists build low-cost microscope to study living cells in zero gravity

The Biophysical Journal names Denis V. Titov the 2025 Paper of the Year-Early Career Investigator awardee

Scientists show how your body senses cold—and why menthol feels cool

Scientists deliver new molecule for getting DNA into cells

Study reveals insights about brain regions linked to OCD, informing potential treatments

Does ocean saltiness influence El Niño?

2026 Young Investigators: ONR celebrates new talent tackling warfighter challenges

Genetics help explain who gets the ‘telltale tingle’ from music, art and literature

Many Americans misunderstand medical aid in dying laws

Researchers publish landmark infectious disease study in ‘Science’

New NSF award supports innovative role-playing game approach to strengthening research security in academia

Kumar named to ACMA Emerging Leaders Program for 2026

AI language models could transform aquatic environmental risk assessment

New isotope tools reveal hidden pathways reshaping the global nitrogen cycle

Study reveals how antibiotic structure controls removal from water using biochar

Why chronic pain lasts longer in women: Immune cells offer clues

Toxic exposure creates epigenetic disease risk over 20 generations

More time spent on social media linked to steroid use intentions among boys and men

New study suggests a “kick it while it’s down” approach to cancer treatment could improve cure rates

Milken Institute, Ann Theodore Foundation launch new grant to support clinical trial for potential sarcoidosis treatment

New strategies boost effectiveness of CAR-NK therapy against cancer

Study: Adolescent cannabis use linked to doubling risk of psychotic and bipolar disorders

Invisible harms: drug-related deaths spike after hurricanes and tropical storms

[Press-News.org] Not all diamonds are foreverRice University researchers see nanodiamonds created in coal fade away in seconds