(Press-News.org) A study led by researchers at Stanford's School of Medicine reveals how T cells, the immune system's foot soldiers, respond to an enormous number of potential health threats.

X-ray studies at the Department of Energy's SLAC National Accelerator Laboratory, combined with Stanford biological studies and computational analysis, revealed remarkable similarities in the structure of binding sites, which allow a given T cell to recognize many different invaders that provoke an immune response.

The research demonstrates a faster, more reliable way to identify large numbers of antigens, the targets of the immune response, which could speed the discovery of disease treatments. It also may lead to a better understanding of what T cells recognize when fighting cancers and why they are triggered to attack healthy cells in autoimmune diseases such as diabetes and multiple sclerosis.

"Until now, it often has been a real mystery which antigens T cells are recognizing; there are whole classes of disease where we don't have this information," said Michael Birnbaum, a graduate student who led the research at the School of Medicine in the laboratory of K. Christopher Garcia, the study's senior author and a professor of molecular and cellular physiology and of structural biology.

"Now it's far more feasible to take a T cell that is important in a disease or autoimmune disorder and figure out what antigens it will respond to," Birnbaum said.

T cells are triggered into action by protein fragments, called peptides, displayed on a cell's surface. In the case of an infected cell, peptide antigens from a pathogen can trigger a T cell to kill the infected cell. The research provides a sort of rulebook that can be used with high success to track down antigens likely to activate a given T cell, easing a bottleneck that has constrained such studies.

Combination approach

In the study, researchers exposed a handful of mouse and human T-cell receptors to hundreds of millions of peptides, and found hundreds of peptides that bound to each type. Then they compiled and compared the detailed sequence – the order of the chemical building blocks – of the peptides that bound to each T-cell receptor.

From that sample set, which represents just a tiny fraction of all peptides, a detailed computational analysis identified other likely binding matches. Researchers compared the 3-D structures of T cells and their unique receptors bound to different peptides at SLAC's Stanford Synchrotron Research Lightsource (SSRL).

"The X-ray work at SSRL was a key breakthrough in the study," Birnbaum said. "Very different peptides aligned almost perfectly with remarkably similar binding sites. It took us a while to figure out this structural similarity was a common feature, not an oddity – that a vast number of unique peptides could be recognized in the same way."

Researchers also checked the sequencing of the peptides that were known to bind with a given T cell and found striking similarities there, too.

"T-cell receptors are 'cross-reactive,' but in fairly limited ways. Like a multilingual person who can speak Spanish and French but can't understand Japanese, a receptor can engage with a broad set of peptides related to one another," Birnbaum said.

Impact on biomedical science

Finding out whether a given peptide activates a specific T-cell receptor has been a historically piecemeal process with a 20 to 30 percent success rate, involving burdensome hit-and-miss studies of biological samples. "This latest research provides a framework that can improve the success rate to as high as 90 percent," Birnbaum said.

"This is an important illustration of how SSRL's X-ray-imaging capabilities allow researchers to get detailed structural information on technically very challenging systems," said Britt Hedman, professor of photon science and science director at SSRL. "To understand the factors behind T-cell-receptor binding to peptides will have major impact on biomedical developments, including vaccine design and immunotherapy."

INFORMATION:

Additional contributors included the laboratories of Mark Davis, the Burt and Marion Avery Family Professor at Stanford School of Medicine, and Kai Wucherpfennig at the Dana Farber Cancer Institute and Harvard University. The research was supported by the National Institutes of Health and the Howard Hughes Medical Institute. SSRL is a scientific user facility supported by DOE's Office of Science.

Glenn Roberts Jr. is a science writer at the SLAC National Accelerator Laboratory.

Stanford researchers discover immune system's rules of engagement

2014-05-27

ELSE PRESS RELEASES FROM THIS DATE:

Climate change accelerates hybridization between native and invasive species of trout

2014-05-27

BOZEMAN, Mont. – Scientists have discovered that the rapid spread of hybridization between a native species and an invasive species of trout in the wild is strongly linked to changes in climate.

In the study, stream temperature warming over the past several decades and decreases in spring flow over the same time period contributed to the spread of hybridization between native westslope cutthroat trout and introduced rainbow trout – the world's most widely introduced invasive fish species –across the Flathead River system in Montana and British Columbia, Canada.

Experts ...

New perspectives to the design of molecular cages

2014-05-27

Researchers from the University of Jyväskylä report a new method of building molecular cages. The method involves the exploitation of intermolecular steric effects to control the outcome of a self-assembly reaction.

Molecular cages are composed of organic molecules (ligands) which are bound to metal ions during a self-assembly process. Depending on the prevailing conditions, self-assembly processes urge to maximize the symmetry of the system and thus occupy every required metal binding site. The research group led by docent Manu Lahtinen (University of Jyväskylä, Department ...

Molecules do the triple twist

2014-05-27

An international research team led by Academy Professor Kari Rissanen of the University of Jyväskylä (Finland) and Professor Rainer Herges of the University of Kiel (Germany) has managed to make a triple-Möbius annulene, the most twisted fully conjugated molecule to date, as reported in Nature Chemistry (DOI:10.1038/nchem.1955, published online 25 May 2014).

An everyday analogue of a single twisted Möbius molecule is a Möbius strip. It can be made easily by twisting one end of a paper strip by 180 degrees and then joining the two ends. A triple twisted Möbius molecule ...

Insights into genetics of cleft lip

2014-05-27

Scientists at the European Molecular Biology Laboratory (EMBL) in Heidelberg, have identified how a specific stretch of DNA controls far-off genes to influence the formation of the face. The study, published today in Nature Genetics, helps understand the genetic causes of cleft lip and cleft palate, which are among the most common congenital malformations in humans.

"This genomic region ultimately controls genes which determine how to build a face and genes which produce the basic materials needed to execute this plan", says François Spitz from EMBL, who led the work. ...

Clinical trial reaffirms diet beverages play positive role in weight loss

2014-05-27

May 27, 2014 – A groundbreaking new study published today in Obesity, the journal of The Obesity Society, confirms definitively that drinking diet beverages helps people lose weight.

"This study clearly demonstrates that diet beverages can in fact help people lose weight, directly countering myths in recent years that suggest the opposite effect – weight gain," said James O. Hill, Ph.D., executive director of the University of Colorado Anschutz Health and Wellness Center and a co-author of the study. "In fact, those who drank diet beverages lost more weight and reported ...

Heavily decorated classrooms disrupt attention and learning in young children

2014-05-27

VIDEO:

Maps, number lines, shapes, artwork and other materials tend to cover elementary classroom walls. However, new research from Carnegie Mellon University shows that too much of a good thing may...

Click here for more information.

PITTSBURGH—Maps, number lines, shapes, artwork and other materials tend to cover elementary classroom walls. However, new research from Carnegie Mellon University shows that too much of a good thing may end up disrupting attention and learning in ...

Migrating stem cells possible new focus for stroke treatment

2014-05-27

Two years ago, a new type of stem cell was discovered in the brain that has the capacity to form new cells. The same research group at Lund University in Sweden has now revealed that these stem cells, which are located in the outer blood vessel wall, appear to be involved in the brain reaction following a stroke.

The findings show that the cells, known as pericytes, drop out from the blood vessel, proliferate and migrate to the damaged brain area where they are converted into microglia cells, the brain's inflammatory cells.

Pericytes are known to contribute to tissue ...

Health issues, relationship changes trigger economic spirals for low-income rural families

2014-05-27

When it comes to the factors that can send low-income rural families into a downward spiral, health issues and relationship changes appear to be major trigger events. Fortunately, support networks – in particular, extended families – can help ease these poverty spells, according to new research from the NH Agricultural Experiment Station at the University of New Hampshire College of Life Sciences and Agriculture.

The research was conducted by Elizabeth Dolan, emeritus associate professor of family studies at UNH, and her colleagues Sheila Mammen at the University of ...

Africa's longest-known terrestrial wildlife migration discovered

2014-05-27

WASHINGTON, DC - Researchers have documented the longest-known terrestrial migration of wildlife in Africa – up to several thousand zebra covering a distance of 500km (more than 300 miles) – according to World Wildlife Fund (WWF).

Using GPS collars on eight adult Plains zebra (Equus quagga), WWF and Namibia's Ministry of Environment and Tourism (MET), in collaboration with Elephants Without Borders (EWB) and Botswana's Department of Wildlife and National Parks, tracked two consecutive years of movement back and forth between the Chobe River in Namibia and Botswana's Nxai ...

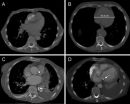

Chest CT helps predict cardiovascular disease risk

2014-05-27

OAK BROOK, Ill. – Incidental chest computed tomography (CT) findings can help identify individuals at risk for future heart attacks and other cardiovascular events, according to a new study published online in the journal Radiology.

"In addition to diagnostic purposes, chest CT can be used for the prediction of cardiovascular disease," said Pushpa M. Jairam, M.D., Ph.D., from the University Medical Center Utrecht, in Utrecht, the Netherlands. "With this study, we have taken a new perspective by providing a different approach for cardiovascular disease risk prediction ...