(Press-News.org) Seemingly ordinary, water has quite puzzling behavior. Why, for example, does ice float when most liquids crystallize into dense solids that sink?

Using a computer model to explore water as it freezes, a team at Princeton University has found that water's weird behaviors may arise from a sort of split personality: at very cold temperatures and above a certain pressure, water may spontaneously split into two liquid forms.

The team's findings were reported in the journal Nature.

"Our results suggest that at low enough temperatures water can coexist as two different liquid phases of different densities," said Pablo Debenedetti, the Class of 1950 Professor in Engineering and Applied Science and Princeton's dean for research, and a professor of chemical and biological engineering.

The two forms coexist a bit like oil and vinegar in salad dressing, except that the water separates from itself rather than from a different liquid. "Some of the molecules want to go into one phase and some of them want to go into the other phase," said Jeremy Palmer, a postdoctoral researcher in the Debenedetti lab.

The finding that water has this dual nature, if it can be replicated in experiments, could lead to better understanding of how water behaves at the cold temperatures found in high-altitude clouds where liquid water can exist below the freezing point in a "supercooled" state before forming hail or snow, Debenedetti said. Understanding how water behaves in clouds could improve the predictive ability of current weather and climate models, he said.

The new finding serves as evidence for the "liquid-liquid transition" hypothesis, first suggested in 1992 by Eugene Stanley and co-workers at Boston University and the subject of recent debate. The hypothesis states that the existence of two forms of water could explain many of water's odd properties — not just floating ice but also water's high capacity to absorb heat and the fact that water becomes more compressible as it gets colder.

At cold temperatures, the molecules in most liquids slow to a sedate pace, eventually settling into a dense and orderly solid that sinks if placed in liquid. Ice, however, floats in water due to the unusual behavior of its molecules, which as they get colder begin to push away from each other. The result is regions of lower density — that is, regions with fewer molecules crammed into a given volume — amid other regions of higher density. As the temperature falls further, the low-density regions win out, becoming so prevalent that they take over the mixture and freeze into a solid that is less dense than the original liquid.

The work by the Princeton team suggests that these low-density and high-density regions are remnants of the two liquid phases that can coexist in a fragile, or "metastable" state, at very low temperatures and high pressures. "The existence of these two forms could provide a unifying theory for how water behaves at temperatures ranging from those we experience in everyday life all the way to the supercooled regime," Palmer said.

Since the proposal of the liquid-liquid transition hypothesis, researchers have argued over whether it really describes how water behaves. Experiments would settle the debate, but capturing the short-lived, two-liquid state at such cold temperatures and under pressure has proved challenging to accomplish in the lab.

Instead, the Princeton researchers used supercomputers to simulate the behavior of water molecules — the two hydrogens and the oxygen that make up "H2O" — as the temperature dipped below the freezing point.

The team used computer code to represent several hundred water molecules confined to a box, surrounded by an infinite number of similar boxes. As they lowered the temperature in this virtual world, the computer tracked how the molecules behaved.

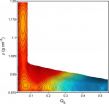

The team found that under certain conditions — about minus 45 degrees Celsius and about 2,400-times normal atmospheric pressure — the virtual water molecules separated into two liquids that differed in density.

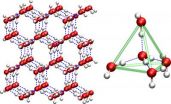

The pattern of molecules in each liquid also was different, Palmer said. Although most other liquids are a jumbled mix of molecules, water has a fair amount of order to it. The molecules link to their neighbors via hydrogen bonds, which form between the oxygen of one molecule and a hydrogen of another. These molecules can link — and later unlink — in a constantly changing network. On average, each H2O links to four other molecules in what is known as a tetrahedral arrangement.

The researchers found that the molecules in the low-density liquid also contained tetrahedral order, but that the high-density liquid was different. "In the high-density liquid, a fifth neighbor molecule was trying to squeeze into the pattern," Palmer said.

The researchers also looked at another facet of the two liquids: the tendency of the water molecules to form rings via hydrogen bonds. Ice consists of six water molecules per ring. Calculations by Fausto Martelli, a postdoctoral research associate advised by Roberto Car, the Ralph W. *31 Dornte Professor in Chemistry, found that in this computer model the average number of molecules per ring decreased from about seven in the high-density liquid to just above six in the low-density liquid, but then climbed slightly before declining again to six molecules per ring as ice, suggesting that there is more to be discovered about how water molecules behave during supercooling.

A better understanding of water's behavior at supercooled temperatures could lead to improvements in modeling the effect of high-altitude clouds on climate, Debenedetti said. Because water droplets reflect and scatter the sunlight coming into the atmosphere, clouds play a role in whether the sun's energy is reflected away from the planet or is able to enter the atmosphere and contribute to warming. Additionally, because water goes through a supercooled phase before forming hail or snow, such research may aid strategies for preventing ice from forming on airplane wings.

"The research is a tour de force of computational physics and provides a splendid academic look at a very difficult problem and a scholarly controversy," said C. Austen Angell, professor of chemistry and biochemistry at Arizona State University, who was not involved in the research. "Using a particular computer model, the Debenedetti group has provided strong support for one of the theories that can explain the outstanding properties of real water in the supercooled region."

In their computer simulations, the team used an updated version of a model noted for its ability to capture many of water's unusual behaviors first developed in 1974 by Frank Stillinger, then at Bell Laboratories in Murray Hill, N.J., and now a senior chemist at Princeton; and Aneesur Rahman, then at the U.S. Argonne National Laboratory. The same model was used to develop the liquid-liquid transition hypothesis.

Collectively, the work took several million computer hours, which would take several human lifetimes using a typical desktop computer, Palmer said. In addition to the initial simulations, the team verified the results using six calculation methods. The computations were performed at Princeton's High-Performance Computing Research Center's Terascale Infrastructure for Groundbreaking Research in Science and Engineering (TIGRESS).

INFORMATION:The team included Yang Liu, who earned her doctorate at Princeton in 2012, and Athanassios Panagiotopoulos, the Susan Dod Brown Professor of Chemical and Biological Engineering.

Familiar yet strange: Water's 'split personality' revealed by computer model

2014-06-18

ELSE PRESS RELEASES FROM THIS DATE:

Collecting light with artificial moth eyes

2014-06-18

Rust – iron oxide – could revolutionise solar cell technology. This usually unwanted substance can be used to make photoelectrodes which split water and generate hydrogen. Sunlight is thereby directly converted into valuable fuel rather than first being used to generate electricity. Unfortunately, as a raw material iron oxide has its limitations. Although it is unbelievably cheap and absorbs light in exactly the wavelength region where the sun emits the most energy, it conducts electricity very poorly and must therefore be used in the form of an extremely thin film in ...

Breathalyzer test may detect deadliest cancer

2014-06-18

Lung cancer causes more deaths in the U.S. than the next three most common cancers combined (colon, breast, and pancreatic). The reason for the striking mortality rate is simple: poor detection. Lung cancer attacks without leaving any fingerprints, quietly afflicting its victims and metastasizing uncontrollably – to the point of no return.

Now a new device developed by a team of Israeli, American, and British cancer researchers may turn the tide by both accurately detecting lung cancer and identifying its stage of progression. The breathalyzer test, embedded with a "NaNose" ...

Scripps Research Institute scientists reveal molecular 'yin-yang' of blood vessel growth

2014-06-18

LA JOLLA, CA—June 18, 2014 —Biologists at The Scripps Research Institute (TSRI) have discovered a crucial process that regulates the development of blood vessels. The finding could lead to new treatments for disorders involving abnormal blood vessel growth, including common disorders such as diabetic retinopathy and cancer.

"Essentially we've shown how the protein SerRS acts as a brake on new blood vessel growth and pairs with the growth-promoting transcription factor c-Myc to bring about proper vascular development," said TSRI Professor Xiang-Lei Yang. "They act as the ...

Inflammation in fat tissue helps prevent metabolic disease

2014-06-18

DALLAS – June 18, 2014 – Chronic tissue inflammation is typically associated with obesity and metabolic disease, but new research from UT Southwestern Medical Center now finds that a level of "healthy" inflammation is necessary to prevent metabolic diseases, such as fatty liver.

"There is such a thing as 'healthy' inflammation, meaning inflammation that allows the tissue to grow and has overall benefits to the tissue itself and the whole body," said Dr. Philipp Scherer, Director of the Touchstone Center for Diabetes Research and Professor of Internal Medicine and Cell ...

Unlocking the therapeutic potential of SLC13 transporters

2014-06-18

Researchers have provided the first functional analysis of a member of a family of transporter proteins implicated in diabetes, obesity, and lifespan. The study appears in the June issue of The Journal of General Physiology.

Members of the SLC13 transporter family play a key role in the regulation of fat storage, insulin resistance, and other processes. Some SLC13 transporters mediate the transport of Krebs cycle intermediates—compounds essential for the body's metabolic activity—across the cell membrane. Previous studies have shown that loss of one member of this family ...

Penn team links placental marker of prenatal stress to brain mitochondrial dysfunction

2014-06-18

When a woman experiences a stressful event early in pregnancy, the risk of her child developing autism spectrum disorders or schizophrenia increases. Yet how maternal stress is transmitted to the brain of the developing fetus, leading to these problems in neurodevelopment, is poorly understood.

New findings by University of Pennsylvania School of Veterinary Medicine scientists suggest that an enzyme found in the placenta is likely playing an important role. This enzyme, O-linked-N-acetylglucosamine transferase, or OGT, translates maternal stress into a reprogramming ...

Study examines how brain 'reboots' itself to consciousness after anesthesia

2014-06-18

One of the great mysteries of anesthesia is how patients can be temporarily rendered completely unresponsive during surgery and then wake up again, with their memories and skills intact.

A new study by Dr. Andrew Hudson, an assistant professor in anesthesiology at the David Geffen School of Medicine at UCLA, and colleagues provides important clues about the processes used by structurally normal brains to navigate from unconsciousness back to consciousness. Their findings are currently available in the early online edition of the Proceedings of the National Academy of ...

Scripps Florida scientists pinpoint how genetic mutation causes early brain damage

2014-06-18

JUPITER, FL, June 18, 2014 – Scientists from the Florida campus of The Scripps Research Institute (TSRI) have shed light on how a specific kind of genetic mutation can cause damage during early brain development that results in lifelong learning and behavioral disabilities. The work suggests new possibilities for therapeutic intervention.

The study, which focuses on the role of a gene known as Syngap1, was published June 18, 2014, online ahead of print by the journal Neuron. In humans, mutations in Syngap1 are known to cause devastating forms of intellectual disability ...

Blocking brain's 'internal marijuana' may trigger early Alzheimer's deficits, study shows

2014-06-18

A new study led by investigators at the Stanford University School of Medicine has implicated the blocking of endocannabinoids — signaling substances that are the brain's internal versions of the psychoactive chemicals in marijuana and hashish — in the early pathology of Alzheimer's disease.

A substance called A-beta — strongly suspected to play a key role in Alzheimer's because it's the chief constituent of the hallmark clumps dotting the brains of people with Alzheimer's — may, in the disease's earliest stages, impair learning and memory by blocking the natural, beneficial ...

Groundbreaking model explains how the brain learns to ignore familiar stimuli

2014-06-18

Dublin, June 18th, 2014 – A neuroscientist from Trinity College Dublin has proposed a new, ground-breaking explanation for the fundamental process of 'habituation', which has never been completely understood by neuroscientists.

Typically, our response to a stimulus is reduced over time if we are repeatedly exposed to it. This process of habituation enables organisms to identify and selectively ignore irrelevant, familiar objects and events that they encounter again and again. Habituation therefore allows the brain to selectively engage with new stimuli, or those that ...