(Press-News.org) Researchers from North Carolina State University and the University of Minnesota have found for the first time that genetically identical strains of bacteria can respond very differently to the presence of sugars and other organic molecules in the environment, with some individual bacteria devouring the sugars and others ignoring it.

"This highlights the complexity of bacterial behaviors and their response to environmental conditions, and how much we still need to learn," says Dr. Chase Beisel, an assistant professor of chemical and biomolecular engineering at NC State and senior author of a paper describing the work. "This is one additional piece of the puzzle that could help us understand the behaviors of bacterial pathogens or the population dynamics of the micro-organisms that live in our guts."

The researchers grew a non-pathogenic strain of E. coli in liquid culture, with each culture rich in a different type of sugar. Bacteria produce different protein pumps and enzymes that are dedicated to taking in and breaking down specific types of sugar, but only when the relevant sugar is present.

To explore how individual bacteria respond to different sugars, the research team genetically modified the bacteria to create fluorescent proteins whenever they produced the pumps or enzymes. These fluorescent proteins acted as visual cues that the researchers could use to see how individual bacteria responded to the presence of a particular sugar.

The researchers tested the E. coli's responses to eight different sugars. For four of those sugars, all of the bacteria responded identically, increasing consumption in response to greater concentrations of sugar molecules in the culture.

But the bacteria responded differently to the other four molecules, exhibiting a wide range of behaviors.

"The behaviors were all over the place," Beisel says.

"While this is the first time we've seen such divergent behavior from bacteria regarding sugars, it's consistent with 'bet-hedging' behaviors that have been reported for bacteria in other contexts," he adds. "Bet hedging means that at least some of the bacteria will survive when faced with new environments."

The researchers also performed mathematical modeling, which found that the bacteria's diverse behaviors could be traced to the production of pumps and enzymes in the presence of sugar.

One question this study raises is whether this bet-hedging behavior is exhibited by bacteria used to convert sugars into biofuels. If it is, that would mean that a percentage of the bacteria aren't converting the sugar – which would mean the system wasn't working at peak efficiency.

"But this work raises a lot of other questions as well," Beisel says. Why does this happen in the presence of some sugars but not others? What are the circumstances in which this bet-hedging behavior actually helps the bacteria? What happens in the presence of multiple sugars? And what does this mean for bacteria in real-world conditions? For example, how would this behavior impact the introduction of probiotics – or pathogens – into the human gut?

"These are all questions we'd love to answer," Beisel says.

INFORMATION:

The paper, "Bacterial sugar utilization gives rise to distinct single-cell behaviors," is published online in the journal Molecular Microbiology. Lead author of the paper is Taliman Afroz, a Ph.D. student at NC State. The paper was co-authored by Drs. Konstantinos Biliouris and Yiannis Kaznessis of the University of Minnesota. The research was supported by the National Institutes of Health under grant GM086865; the National Science Foundation, under grants CBET-0425882 and CBET-0644792, and the National Computational Science Alliance under grant TG-MCA04N033.

When faced with some sugars, bacteria can be picky eaters

2014-07-08

ELSE PRESS RELEASES FROM THIS DATE:

A possible pathway for inhibiting liver and colon cancer is found

2014-07-08

A group of scientists from Spain, the UK and the United States has revealed the structure of a protein complex involved in liver and colon cancers. Both of these types of cancer are of significant social and clinical relevance as in 2012 alone, liver cancer was responsible for the second highest mortality rate worldwide, with colon cancer appearing third in the list.

The international team from CIC bioGUNE, the University of Liverpool and the US research centre USC-UCLA has successfully unravelled the mechanism by which two proteins, MATα2 and MATβ, bind to ...

KAIST develops TransWall, a transparent touchable display wall

2014-07-08

Daejeon, Republic of Korea, July 8, 2014 – At a busy shopping mall, shoppers walk by store windows to find attractive items to purchase. Through the windows, shoppers can see the products displayed, but may have a hard time imagining doing something beyond just looking, such as touching the displayed items or communicating with sales assistants inside the store. With TransWall, however, window shopping could become more fun and real than ever before.

Woohun Lee, a professor of Industrial Design at KAIST, and his research team have recently developed TransWall, a two-sided, ...

Travel campaign fuels $1B rise in hospitality industry

2014-07-08

EAST LANSING, Mich. --- The Obama administration's controversial travel-promotion program has generated a roughly $1 billion increase in the value of the hospitality industry and stands to benefit the U.S. economy in the long run.

So finds the first scientific evidence, from a Michigan State University-led study, showing a positive economic impact of the Travel Promotion Act. Congress is currently reviewing whether to extend the law, which went into effect in March 2010.

"We found positive stock market reactions related to the passage of the act and therefore agree ...

Low doses of arsenic cause cancer in male mice

2014-07-08

Mice exposed to low doses of arsenic in drinking water, similar to what some people might consume, developed lung cancer, researchers at the National Institutes of Health have found.

Arsenic levels in public drinking water cannot exceed 10 parts per billion (ppb), which is the standard set by the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency. However, there are no established standards for private wells, from which millions of people get their drinking water.

In this study, the concentrations given to the mice in their drinking water were 50 parts per billion (ppb), 500 ppb, ...

Recalled yogurt contained highly pathogenic mold

2014-07-08

DURHAM, N.C. -- Samples isolated from Chobani yogurt that was voluntarily recalled in September 2013 have been found to contain the most virulent form of a fungus called Mucor circinelloides, which is associated with infections in immune-compromised people.

The study by Duke University scientists shows that this strain of the fungus can survive in a mouse and be found in its feces as many as 10 days after ingestion.

In August and September 2013, more than 200 consumers of contaminated Chobani Greek Yogurt became ill with vomiting, nausea and diarrhea. The U.S. Food ...

Shining light on the 100-year mystery of birds sensing spring for offspring

2014-07-08

Nagoya, Japan – Professor Takashi Yoshimura and colleagues of the Institute of Transformative Bio-Molecules (WPI-ITbM) of Nagoya University have finally found the missing piece in how birds sense light by identifying a deep brain photoreceptor in Japanese quails, in which the receptor directly responds to light and controls seasonal breeding activity. Although it has been known for over 100 years that vertebrates apart from mammals detect light deep inside their brains, the true nature of the key photoreceptor has remained to be a mystery up until now. This study led by ...

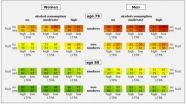

A healthy lifestyle adds years to life

2014-07-08

Cardiovascular diseases (CVDs), cancer, diabetes and chronic respiratory disorders - the incidence of these non-communicable diseases (NCDs) is constantly rising in industrialised countries. The Federal Office of Public Health (FOPH) is, therefore, in the process of developing a national prevention strategy with a view to improving the population's health competence and encouraging healthier behaviour. Attention is focusing, amongst other things, on the main risk factors for these diseases which are linked to personal behaviour – i.e. tobacco smoking, an unhealthy diet, ...

HIV study leads to insights into deadly infection

2014-07-08

Research led by the University of Adelaide has provided new insights into how the HIV virus greatly boosts its chances of spreading infection, and why HIV is so hard to combat.

HIV infects human immune cells by turning the infection-fighting proteins of these cells into a "backdoor key" that lets the virus in. Recent research has found that another protein is involved as well. A peptide in semen that sticks together and forms structures known as "amyloid fibrils" enhances the virus's infection rate by up to an astonishing 10,000 times.

How and why these fibrils enhance ...

AAU launches STEM education initiative website, announces STEM network conference

2014-07-08

The Association of American Universities (AAU), an association of leading public and private research universities, today launched the AAU STEM Initiative Hub, a website that will both support and widen the impact of the association's initiative to improve the quality of

undergraduate teaching and learning in science, technology, engineering and mathematics (STEM) fields at its member institutions.

AAU has partnered with HUBzero, a web-based platform for scientific collaboration developed and managed by Purdue University, to create the AAU STEM Initiative Hub. The new ...

Silicon sponge improves lithium-ion battery performance

2014-07-08

RICHLAND, Wash. – The lithium-ion batteries that power our laptops and electric vehicles could store more energy and run longer on a single charge with the help of a sponge-like silicon material.

Researchers developed the porous material to replace the graphite traditionally used in one of the battery's electrodes, as silicon has more than 10 times the energy storage capacity of graphite. A paper describing the material's performance as a lithium-ion battery electrode was published today in Nature Communications.

"Silicon has long been sought as a way to improve the ...