(Press-News.org)

NEW YORK, NY — Evidence from human famines and animal studies suggests that starvation can affect the health of descendants of famished individuals. But how such an acquired trait might be transmitted from one generation to the next has not been clear. A new study, involving roundworms, shows that starvation induces specific changes in so-called small RNAs and that these changes are inherited through at least three consecutive generations, apparently without any DNA involvement. The study, conducted by Columbia University Medical Center (CUMC) researchers, offers intriguing new evidence that the biology of inheritance is more complicated than previously thought. The study was published in the July 10 online edition of the journal Cell.

The idea that acquired traits can be inherited dates back to Jean Baptiste Larmarck, who proposed that species evolve when individuals adapt to their environment and transmit the acquired traits to their offspring. According to Lamarckian inheritance, for example, giraffes developed elongated long necks as they stretched to feed on the leaves of high trees, an acquired advantage that was inherited by subsequent generations. In contrast, Charles Darwin later theorized that random mutations that offer an organism a competitive advantage drive a species' evolution. In the case of the giraffe, individuals that happened to have slightly longer necks had a better chance of securing food and thus were able to have more offspring. The subsequent discovery of hereditary genetics supported Darwin's theory, and Lamarck's ideas faded into obscurity.

"However, events like the Dutch famine of World War II have compelled scientists to take a fresh look at acquired inheritance," said study leader Oliver Hobert, PhD, professor of biochemistry and molecular biophysics and a Howard Hughes Medical Institute Investigator at CUMC. Starving women who gave birth during the famine had children who were unusually susceptible to obesity and other metabolic disorders, as were their grandchildren. Controlled animal experiments have found similar results, including a study in rats demonstrating that chronic high-fat diets in fathers result in obesity in their female offspring.

In a 2011 study, Oded Rechavi, a postdoctoral fellow in Dr. Hobert's laboratory, found that roundworms (C. elegans) that developed resistance to a virus were able to pass along that immunity to their progeny for many consecutive generations. The immunity was transferred in the form of small viral-silencing RNAs working independently of the organism's genome. Other studies have reported similar findings, but none of these addressed whether a biological response induced by natural circumstances, such as famine, could be passed on to subsequent generations.

To address this question, Dr. Hobert's team starved roundworms for six days and then examined their cells for molecular changes. The starved roundworms, but not controls, were found to have generated a specific set of small RNAs. (Small RNAs are involved in various aspects of gene expression but do not code for proteins.) The small RNAs persisted for at least three generations, even though the worms were fed normal diets. The researchers also found that these small RNAs target genes with roles in nutrition.

Since these small RNAs are produced only in response to starvation, they had to have been passed from one generation to another. "We know from other studies that small RNAs can be transported from cell to cell around the body," said Dr. Hobert. "So, it's conceivable that the starvation-induced small RNAs found their way into the worms' germ cells — that is, their sperm or eggs. When the worms reproduced, the small RNAs could have been transmitted generationally in the cell body of the germ cells, independent of the DNA."

The study also found that the progeny of the starved worms had a longer life span than the progeny of the controls. "We have not shown that the starvation-induced small RNAs were responsible for the increased longevity—it's just a correlation," said Dr. Hobert. "But it's possible that these small RNAs provided a means for the worms to control the expression of relevant genes in later generations."

The findings have no immediate clinical application. "However, they do suggest that we should be aware of other things—beyond pure DNA changes—that may have a long-term impact on the health of an organism," said Dr. Hobert. "In other words, something that happened to one generation, whether famine or some other traumatic event, may be relevant to the health of its descendants for generations."

INFORMATION:

The paper is titled, "Starvation-Induced Transgenerational Inheritance of Small RNAs in C. elegans." The other authors are Oded Rechavi (Tel Aviv University, Tel Aviv, Israel, and CUMC), Leah Houri-Ze'evi (Tel Aviv University), Sarit Anava (Tel Aviv University),Wee Siong Sho Goh (Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory, Cold Spring Harbor, NY),Sze Yen Kerk(CUMC), and Gregory J. Hannon (Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory). DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.cell.2014.06.020

The authors declare no financial or other conflicts of interests.

The study was supported by the Howard Hughes Medical Institute.

Columbia University Medical Center provides international leadership in basic, preclinical, and clinical research; medical and health sciences education; and patient care. The medical center trains future leaders and includes the dedicated work of many physicians, scientists, public health professionals, dentists, and nurses at the College of Physicians and Surgeons, the Mailman School of Public Health, the College of Dental Medicine, the School of Nursing, the biomedical departments of the Graduate School of Arts and Sciences, and allied research centers and institutions. Columbia University Medical Center is home to the largest medical research enterprise in New York City and State and one of the largest faculty medical practices in the Northeast. For more information, visit cumc.columbia.edu or columbiadoctors.org.

Study shows how effects of starvation can be passed to future generations

2014-07-17

ELSE PRESS RELEASES FROM THIS DATE:

How does working part-time versus working full-time affect breastfeeding goals?

2014-07-17

Los Angeles, CA -- Breastfeeding is known to provide significant health benefits for both infants and their mothers. However, while many women intend to breastfeed despite returning to work, a new study finds that mothers who plan to breastfeed for at least three months but return to work full-time are less likely to meet their breastfeeding goals. Conversely, there is no association between women who return to work part-time and failure to reach the breastfeeding goal of at least three months. This new study was published today in the Journal of Human Lactation.

Studying ...

Improving the cost and efficiency of renewable energy storage

2014-07-17

A major challenge in renewable energy is storage. A common approach is a reaction that splits water into oxygen and hydrogen, and uses the hydrogen as a fuel to store energy. The efficiency of 'water splitting' depends heavily on a solid substance called a catalyst. However, only the surface of the catalyst acts on the reaction, while its bulk is inactive. This restricts how much catalyst can be used, and limits the efficiency of water splitting in energy systems. Publishing in Nature Communications, EPFL scientists have developed a new method for maximizing the catalyst's ...

For the sickest emergency patients, death risk is lowest at busiest emergency centers

2014-07-17

ANN ARBOR, Mich. — When a medical emergency strikes, our gut tells us to get to the nearest hospital quickly. But a new study suggests that busier emergency centers may actually give the best chance of surviving – especially for people suffering life-threatening medical crises.

In fact, the analysis finds that patients admitted to a hospital after an emergency had a 10 percent lower chance of dying in the hospital if they initially went to one of the nation's busiest emergency departments, compared with the least busy.

The risk of dying differed even more for patients ...

Best anticoagulants after orthopedic procedures depends on type of surgery

2014-07-17

Current guidelines do not distinguish between aspirin and more potent blood thinners for protecting against blood clots in patients who undergo major orthopedic operations, leaving the decision up to individual clinicians. A new analysis published today in the Journal of Hospital Medicine provides much-needed information that summarizes existing studies about which medications are best after different types of surgery.

Every year, hundreds of thousands of Americans undergo major orthopedic surgery such as hip and knee replacements and hip fracture repairs. Patients undergoing ...

Findings suggest antivirals underprescribed for patients at risk for flu complications

2014-07-17

Patients likely to benefit the most from antiviral therapy for influenza were prescribed these drugs infrequently during the 2012-2013 influenza season, while antibiotics may have been overprescribed. Published in Clinical Infectious Diseases and now available online, the findings suggest more efforts are needed to educate clinicians about the appropriate use of antivirals and antibiotics in the outpatient setting.

Influenza is a significant cause of mortality and morbidity, resulting in more than 200,000 hospitalizations in the U.S. each year, on average. While annual ...

New view of Rainier's volcanic plumbing

2014-07-17

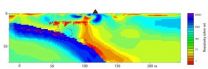

SALT LAKE CITY, July 17, 2014 – By measuring how fast Earth conducts electricity and seismic waves, a University of Utah researcher and colleagues made a detailed picture of Mount Rainier's deep volcanic plumbing and partly molten rock that will erupt again someday.

"This is the most direct image yet capturing the melting process that feeds magma into a crustal reservoir that eventually is tapped for eruptions," says geophysicist Phil Wannamaker, of the university's Energy & Geoscience Institute and Department of Civil and Environmental Engineering. "But it does not provide ...

Asthma drugs suppress growth

2014-07-17

Corticosteroid drugs that are given by inhalers to children with asthma may suppress their growth, evidence suggests. Two new systematic reviews published in The Cochrane Library focus on the effects of inhaled corticosteroid drugs (ICS) on growth rates. The authors found children's growth slowed in the first year of treatment, although the effects were minimised by using lower doses.

Inhaled corticosteroids are prescribed as first-line treatments for adults and children with persistent asthma. They are the most effective drugs for controlling asthma and clearly reduce ...

Niacin too dangerous for routine cholesterol therapy

2014-07-17

CHICAGO --- After 50 years of being a mainstay cholesterol therapy, niacin should no longer be prescribed for most patients due to potential increased risk of death, dangerous side effects and no benefit in reducing heart attacks and strokes, writes Northwestern Medicine® preventive cardiologist Donald Lloyd-Jones, M.D., in a New England Journal of Medicine editorial.

Lloyd-Jones's editorial is based on a large new study published in the journal that looked at adults, ages 50 to 80, with cardiovascular disease who took extended-release niacin (vitamin B3) and laropiprant ...

NIH scientists identify gene linked to fatal inflammatory disease in children

2014-07-17

Investigators have identified a gene that underlies a very rare but devastating autoinflammatory condition in children. Several existing drugs have shown therapeutic potential in laboratory studies, and one is currently being studied in children with the disease, which the researchers named STING-associated vasculopathy with onset in infancy (SAVI). The findings appeared online today in the New England Journal of Medicine. The research was done at the National Institute of Arthritis and Musculoskeletal and Skin Diseases (NIAMS), part of the National Institutes of Health.

"Not ...

No-wait data centers

2014-07-17

Big websites usually maintain their own "data centers," banks of tens or even hundreds of thousands of servers, all passing data back and forth to field users' requests. Like any big, decentralized network, data centers are prone to congestion: Packets of data arriving at the same router at the same time are put in a queue, and if the queues get too long, packets can be delayed.

At the annual conference of the ACM Special Interest Group on Data Communication, in August, MIT researchers will present a new network-management system that, in experiments, reduced the average ...