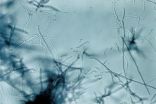

(Press-News.org) A person's home is their castle, and they populate it with their own subjects: millions and millions of bacteria.

A study published today in Science provides a detailed analysis of the microbes that live in houses and apartments. The study was conducted by researchers from the U.S. Department of Energy's Argonne National Laboratory and the University of Chicago.

The results shed light on the complicated interaction between humans and the microbes that live on and around us. Mounting evidence suggests that these microscopic, teeming communities play a role in human health and disease treatment and transmission.

"We know that certain bacteria can make it easier for mice to put on weight, for example, and that others influence brain development in young mice," said Argonne microbiologist Jack Gilbert, who led the study. "We want to know where these bacteria come from, and as people spend more and more time indoors, we wanted to map out the microbes that live in our homes and the likelihood that they will settle on us.

"They are essential for us to understand our health in the 21st century," he said.

The Home Microbiome Project followed seven families, which included eighteen people, three dogs and one cat, over the course of six weeks. The participants in the study swabbed their hands, feet and noses daily to collect a sample of the microbial populations living in and on them. They also sampled surfaces in the house, including doorknobs, light switches, floors and countertops.

Then the samples came to Argonne, where researchers performed DNA analysis to characterize the different species of microbes in each sample.

"We wanted to know how much people affected the microbial community on a house's surfaces and on each other," Gilbert said.

They found that people substantially affected the microbial communities in a house—when three of the families moved, it took less than a day for the new house to look just like the old one, microbially speaking.

Regular physical contact between individuals also mattered—in one home where two of the three occupants were in a relationship with one another, the couple shared many more microbes. Married couples and their young children also shared most of their microbial community.

Within a household, hands were the most likely to have similar microbes, while noses showed more individual variation.

Adding pets changed the makeup as well, Gilbert said—they found more plant and soil bacteria in houses with indoor-outdoor dogs or cats.

In at least one case, the researchers tracked a potentially pathogenic strain of bacteria called Enterobacter, which first appeared on one person's hands, then the kitchen counter, and then another person's hands.

"This doesn't mean that the countertop was definitely the mode of transmission between the two humans, but it's certainly a smoking gun," Gilbert said.

"It's also quite possible that we are routinely exposed to harmful bacteria—living on us and in our environment—but it only causes disease when our immune systems are otherwise disrupted."

Home microbiome studies also could potentially serve as a forensic tool, Gilbert said. Given an unidentified sample from a floor in this study, he said, "we could easily predict which family it came from."

The research also suggests that when a person (and their microbes) leaves a house, the microbial community shifts noticeably in a matter of days.

"You could theoretically predict whether a person has lived in this location, and how recently, with very good accuracy," he said.

INFORMATION:

Researchers used Argonne's Magellan cloud computing system to analyze the data; additional support came from the University of Chicago Research Computing Center.

The paper, "Longitudinal analysis of microbial interaction between humans and the indoor environment," was published today in Science.

The study was funded by the Alfred P. Sloan Foundation. Additional funding also came from the National Institutes of Health, the Environmental Protection Agency, and the National Science Foundation.

Other Argonne researchers on the study included Argonne computational biologist Peter Larsen, postdoctoral researchers Daniel Smith, Kim Handley, and Nicole Scott, and contractors Sarah Owens and Jarrad Hampton-Marcell. University of Chicago graduate students Sean Gibbons and Simon Lax contributed to the paper, as well as collaborators from Washington University in St. Louis and the University of Colorado at Boulder.

The University of Chicago Medicine and Biological Sciences is one of the nation's leading academic medical institutions. It comprises the Pritzker School of Medicine, a top medical school in the nation; the University of Chicago Biological Sciences Division; and the University of Chicago Medical Center, which recently opened the Center for Care and Discovery, a $700 million specialty medical facility. Twelve Nobel Prize winners in physiology or medicine have been affiliated with the University of Chicago Medicine.

Argonne National Laboratory seeks solutions to pressing national problems in science and technology. The nation's first national laboratory, Argonne conducts leading-edge basic and applied scientific research in virtually every scientific discipline. Argonne researchers work closely with researchers from hundreds of companies, universities, and federal, state and municipal agencies to help them solve their specific problems, advance America's scientific leadership and prepare the nation for a better future. With employees from more than 60 nations, Argonne is managed by UChicago Argonne, LLC for the U.S. Department of Energy's Office of Science. For more visit http://www.anl.gov.

DOE's Office of Science is the single largest supporter of basic research in the physical sciences in the United States, and is working to address some of the most pressing challenges of our time. For more information, please visit http://www.science.energy.gov.

Home is where the microbes are

Home Microbiome Project announces results of study on household microbes

2014-08-28

ELSE PRESS RELEASES FROM THIS DATE:

New DNA study unravels the settlement history of the New World Arctic

2014-08-28

We know people have lived in the New World Arctic for about 5,000 years. Archaeological evidence clearly shows that a variety of cultures survived the harsh climate in Alaska, Canada and Greenland for thousands of years. Despite this, there are several unanswered questions about these people: Where did they come from? Did they come in several waves? When did they arrive? Who are their descendants? And who can call themselves the indigenous peoples of the Arctic? We can now answer some of these questions, thanks to a comprehensive DNA study of current and former inhabitants ...

Penn-NIH team discover new type of cell movement

2014-08-28

VIDEO:

Penn and NIH researchers have demonstrated a never-before characterized type of cell movement. In this video, a cell's vimentin cytoskeleton (green) pulls the nucleus (red) forward to generate a high-pressure...

Click here for more information.

For decades, researchers have used petri dishes to study cell movement. These classic tissue culture tools, however, only permit two-dimensional movement, very different from the three-dimensional movements that cells make in a ...

How the zebrafish gets its stripes

2014-08-28

This news release is available in German. The zebrafish, a small fresh water fish, owes its name to a striking pattern of blue stripes alternating with golden stripes. Three major pigment cell types, black cells, reflective silvery cells, and yellow cells emerge during growth in the skin of the tiny juvenile fish and arrange as a multilayered mosaic to compose the characteristic colour pattern.

While it was known that all three cell types have to interact to form proper stripes, the embryonic origin of the pigment cells that develop the stripes of the adult fish has ...

Watching the structure of glass under pressure

2014-08-28

Glass has many applications that call for different properties, such as resistance to thermal shock or to chemically harsh environments. Glassmakers commonly use additives such as boron oxide to tweak these properties by changing the atomic structure of glass. Now researchers at the University of California, Davis, have for the first time captured atoms in borosilicate glass flipping from one structure to another as it is placed under high pressure.

The findings may have implications for understanding how glasses and similar "amorphous" materials respond at the atomic ...

Bradley Hospital collaborative study identifies genetic change in autism-related gene

2014-08-28

PROVIDENCE, R.I. – A new study from Bradley Hospital has identified a genetic change in a recently identified autism-associated gene, which may provide further insight into the causes of autism. The study, now published online in the Journal of Medical Genetics, presents findings that likely represent a definitive clinical marker for some patients' developmental disabilities.

Using whole-exome sequencing – a method that examines the parts of genes that regulate protein, called exons - the team identified a genetic change in a newly recognized autism-associated gene, Activity-Dependent ...

Yale study identifies possible bacterial drivers of IBD

2014-08-28

Yale University researchers have identified a handful of bacterial culprits that may drive inflammatory bowel diseases (IBD) such as Crohn's disease and ulcerative colitis, using patients' own intestinal immune responses as a guide.

The findings are published Aug. 28 in the journal Cell.

Trillions of bacteria exist within the human intestinal microbiota, which plays a critical role in the development and progression of IBD. Yet it's thought that only a small number of bacterial species affect a person's susceptibility to IBD and its potential severity.

"A handful ...

Drug shows promise against Sudan strain of Ebola in mice

2014-08-28

August 28, 2014 — (BRONX, NY) — Researchers from Albert Einstein College of Medicine of Yeshiva University and other institutions have developed a potential antibody therapy for Sudan ebolavirus (SUDV), one of the two most lethal strains of Ebola. A different strain, the Zaire ebolavirus (EBOV), is now devastating West Africa. First identified in 1976, SUDV has caused numerous Ebola outbreaks (most recently in 2012) that have killed more than 400 people in total. The findings were reported in ACS Chemical Biology.

Between 30 and 90 percent of people infected with Ebola ...

NASA sees a weaker Tropical Storm Marie

2014-08-28

When NOAA's GOES-West satellite captured an image of what is now Tropical Storm Marie, weakened from hurricane status on August 28, the strongest thunderstorms were located in the southern quadrant of the storm.

NOAA's GOES-West satellite captured an image of Marie on August 28 at 11 a.m. EDT. Bands of thunderstorms circled the storm especially to the north. The National Hurricane Center noted that Marie has continued to produce a small area of convection (rising air that forms the thunderstorms that make up Marie) south and east of the center during some hours on the ...

DeVincenzo study breakthrough in RSV research

2014-08-28

MEMPHIS, Tenn. – The New England Journal of Medicine published research results on Aug. 21 from a clinical trial of a drug shown to safely reduce the viral load and clinical illness of healthy adult volunteers intranasally infected with respiratory syncytial virus (RSV).

Le Bonheur Children's Hospital and the University of Tennessee Health Science Center researcher Infectious Disease Specialist John DeVincenzo, MD, is lead author of this study.

RSV is the most common cause of lower respiratory tract infections in young children in the United States and worldwide. ...

Small molecule acts as on-off switch for nature's antibiotic factory

2014-08-28

DURHAM, N.C. -- Scientists have identified the developmental on-off switch for Streptomyces, a group of soil microbes that produce more than two-thirds of the world's naturally derived antibiotic medicines.

Their hope now would be to see whether it is possible to manipulate this switch to make nature's antibiotic factory more efficient.

The study, appearing August 28 in Cell, found that a unique interaction between a small molecule called cyclic-di-GMP and a larger protein called BldD ultimately controls whether a bacterium spends its time in a vegetative state or ...

LAST 30 PRESS RELEASES:

Cal Poly’s fifth Climate Solutions Now conference to take place Feb. 23-27

Mask-wearing during COVID-19 linked to reduced air pollution–triggered heart attack risk in Japan

Achieving cross-coupling reactions of fatty amide reduction radicals via iridium-photorelay catalysis and other strategies

Shorter may be sweeter: Study finds 15-second health ads can curb junk food cravings

Family relationships identified in Stone Age graves on Gotland

Effectiveness of exercise to ease osteoarthritis symptoms likely minimal and transient

Cost of copper must rise double to meet basic copper needs

A gel for wounds that won’t heal

Iron, carbon, and the art of toxic cleanup

Organic soil amendments work together to help sandy soils hold water longer, study finds

Hidden carbon in mangrove soils may play a larger role in climate regulation than previously thought

Weight-loss wonder pills prompt scrutiny of key ingredient

Nonprofit leader Diane Dodge to receive 2026 Penn Nursing Renfield Foundation Award for Global Women’s Health

Maternal smoking during pregnancy may be linked to higher blood pressure in children, NIH study finds

New Lund model aims to shorten the path to life-saving cell and gene therapies

Researchers create ultra-stretchable, liquid-repellent materials via laser ablation

Combining AI with OCT shows potential for detecting lipid-rich plaques in coronary arteries

SeaCast revolutionizes Mediterranean Sea forecasting with AI-powered speed and accuracy

JMIR Publications’ JMIR Bioinformatics and Biotechnology invites submissions on Bridging Data, AI, and Innovation to Transform Health

Honey bees navigate more precisely than previously thought

Air pollution may directly contribute to Alzheimer’s disease

Study finds early imaging after pediatric UTIs may do more harm than good

UC San Diego Health joins national research for maternal-fetal care

New biomarker predicts chemotherapy response in triple-negative breast cancer

Treatment algorithms featured in Brain Trauma Foundation’s update of guidelines for care of patients with penetrating traumatic brain injury

Over 40% of musicians experience tinnitus; hearing loss and hyperacusis also significantly elevated

Artificial intelligence predicts colorectal cancer risk in ulcerative colitis patients

Mayo Clinic installs first magnetic nanoparticle hyperthermia system for cancer research in the US

Calibr-Skaggs and Kainomyx launch collaboration to pioneer novel malaria treatments

JAX-NYSCF Collaborative and GSK announce collaboration to advance translational models for neurodegenerative disease research

[Press-News.org] Home is where the microbes areHome Microbiome Project announces results of study on household microbes