(Press-News.org) So long, solitons: University of Chicago physicists have shown that a group of scientists were incorrect when they concluded that a mysterious effect found in superfluids indicated the presence of solitons—exotic, solitary waves. Instead, they explain, the result was due to more pedestrian, whirlpool-like structures in the fluid. They published their explanation in the Sept. 19 issue of Physical Review Letters.

The debate began in July 2013, when a group of scientists from the Massachusetts Institute of Technology published results in Nature showing a long-lived structure in a superfluid — a liquid cooled until it flows without friction. The researchers created the structure in a superfluid made of ultra-cold lithium atoms, by hitting half of the fluid with a laser, so that the lithium particles would be in different quantum-mechanical configurations in the two halves.

When they imaged the result, the researchers observed a dark line cutting across the cigar-shaped volume of superfluid, indicating a region where the density of particles in the fluid was lower. This, they concluded, was a soliton, which behaves like a sparsely populated wall between two halves of the fluid, separating the particles found in the two different states. This wall persisted for a long time, and oscillated back and forth across the fluid.

The appearance of the soliton wall was a surprising conclusion, because it didn't fit in with the accepted theories about the behavior of such systems.

"If it were a wall, that would mean that there's some very unusual physics that theorists did not know about going on, so it of course attracted a huge amount of attention," said Peter Scherpelz, a postdoctoral scientist in physics and lead author of the paper.

Ensuing saga

A scientific saga ensued, in which multiple groups from different institutions attempted to understand the result. But the UChicago group—led by Kathryn Levin, professor in physics—was the first to present the correct explanation.

Levin's group tried to reproduce the puzzling result with a computer simulation of a superfluid. The group had developed the simulation thanks to a collaboration with Argonne National Laboratory. Meanwhile, other groups tried their hands at simulations as well. Some concluded that the region of lower density in the fluid was the result not of a soliton but of a vortex ring — a swirling, donut-shaped structure, around which particles circulate. A smoke ring is a well-known example of a vortex ring.

But Levin's group couldn't reproduce these results in their simulation. Instead, they found that a vortex ring was briefly established, but quickly decayed to a simple vortex line, akin to a tornado or whirlpool stretching across the fluid.

Shortly after Levin's group posted their results on the preprint server arXiv, the MIT researchers released their new results in a preprint, explaining that what they had seen were simple vortices—validating the UChicago theory.

"We swam upstream in a way," said Levin. "Not too often theory anticipates experiment, and not too often theory's bold enough to say, 'Wait a minute. We don't agree with what the going story is. We think it had to be something else.'"

Symmetry problems

The problems with the earlier simulations came down to symmetry. Much like a cigar looks the same if you rotate it around its long axis, other teams had assumed in their simulations that the behavior in the fluid was symmetric—an approximation that made it easier for structures like rings to persist, but which didn't account for imperfections that are inevitable in real-world experiments.

The original MIT experiment had also assumed an incorrect symmetry to come to their original conclusion. They measured only a two-dimensional projection of their experiment, meaning that they couldn't distinguish between the three possible structures, because a ring or a wall viewed from the side looks just like a line. The MIT group had incorrectly assumed that the feature was symmetric, and that it sliced all the way through the cigar to form a soliton wall.

Physicists are intrigued by the physics of superfluids in part because they are related to superconductors, which have a multitude of technological applications due to their ability to conduct electricity without any resistance. Superfluids, however, often are an easier system to study. The materials are so similar that the simulation code used by the group was originally developed for superconductors, and modified for superfluids.

Another reason physicists want to understand this system is to study physics out of equilibrium, in which the material hasn't reached a balanced, comfortable state. After the superfluid is hit with the laser, half of the atoms are in a different state than the other half, and they want to return to the same state. Vortices form as the superfluid moves toward equilibrium.

"Everything we know about physics is sort of confined to equilibrium and we're trying really hard to test ourselves and learn what goes on out of equilibrium, because that's a lot of the real world," Levin said.

INFORMATION:

Funding: National Science Foundation, U.S. Department of Energy, and the Hertz Foundation.

Citation: "Phase Imprinting in Equilibrating Fermi Gases: The Transience of Vortex Rings and Other Defects," by Peter Scherpelz, Karmela Padavić, Adam Rançon, Andreas Glatz, Igor S. Aranson, and K. Levin, Physical Review Letters, Vol. 113, Issue 12, Sept. 19, 2014. DOI: 10.1103/PhysRevLett.113.125301.

Deceptive-looking vortex line in superfluid led to twice-mistaken identity

2014-09-30

ELSE PRESS RELEASES FROM THIS DATE:

New discovery approach accelerates identification of potential cancer treatments

2014-09-30

ANN ARBOR—Researchers at the University of Michigan have described a new approach to discovering potential cancer treatments that requires a fraction of the time needed for more traditional methods.

They used the platform to identify a novel antibody that is undergoing further investigation as a potential treatment for breast, ovarian and other cancers.

In research published online in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, researchers in the lab of Stephen Weiss at the U-M Life Sciences Institute detail an approach that replicates the native environment ...

Gene doubling shapes the world: Instant speciation, biodiversity, and the root of our existence

2014-09-30

What do seedless watermelon, salmon, and strawberries all have in common? Unlike most eukaryotic multicellular organisms that have two sets of chromosomes and are diploid, these organisms are all polyploid, meaning they have three or more sets of chromosomes—seedless watermelon and salmon have 3 and 4 sets of chromosomes, respectively, and strawberries have 10! While this might seem surprising, in fact most plant species are polyploid. Polyploidy, or genome doubling, was first discovered over a century ago, but only recently, with the development of molecular tools, has ...

Smithsonian scientists discover coral's best defender against an army of sea stars

2014-09-30

Coral reefs face a suite of perilous threats in today's ocean. From overfishing and pollution to coastal development and climate change, fragile coral ecosystems are disappearing at unprecedented rates around the world. Despite this trend, some species of corals surrounding the island of Moorea in French Polynesia have a natural protector in their tropical environment: coral guard-crabs. New research from the National Museum of Natural History's Smithsonian Marine Station scientist Seabird McKeon and the museum's predoctoral fellow Jenna Moore of the Florida Museum of Natural ...

Asthma symptoms kicking up? Check your exposure to air pollution

2014-09-30

ARLINGTON HEIGHTS, Ill. (September 30, 2014) – People who suffer from asthma may think there's not a lot they can do to control their asthma besides properly taking medications and avoiding allergic triggers.

According to a new article in the Annals of Allergy, Asthma and Immunology, the scientific publication of the American College of Allergy, Asthma and Immunology (ACAAI), asthma sufferers can learn lessons about managing their asthma by examining their lifestyle. The woman described in the Annals article improved her asthma once she and her doctor determined her ...

High-dose vitamin D for ICU patients who are vitamin D deficient does not improve outcomes

2014-09-30

Administration of high-dose vitamin D3 compared with placebo did not reduce hospital length of stay, intensive care unit (ICU) length of stay, hospital mortality, or the risk of death at 6 months among patients with vitamin D deficiency who were critically ill, according to a study published in JAMA. The study is being posted early online to coincide with its presentation at the European Society of Intensive Care Medicine annual congress.

A high prevalence of low vitamin D levels has been confirmed in patients who are critically ill. Many studies suggest that a low vitamin ...

Gut bacteria promote obesity in mice

2014-09-30

A species of gut bacteria called Clostridium ramosum, coupled with a high-fat diet, may cause animals to gain weight. The work is published this week in mBio®, the online open-access journal of the American Society for Microbiology.

A research team from the German Institute of Human Nutrition Potsdam-Rehbruecke in Nuthetal observed that mice harboring human gut bacteria including C. ramosum gained weight when fed a high-fat diet. Mice that did not have C. ramosum were less obese even when consuming a high-fat diet, and mice that had C. ramosum but consumed a low-fat ...

Endoscopists recommend frequent colonoscopies, leading to its overuse

2014-09-30

Boston, MA – A retrospective study led by researchers at Brigham and Women's Hospital (BWH), has found an overuse of colonoscopies for colorectal cancer screening and surveillance. The study demonstrated that endoscopists commonly recommended shorter follow-up intervals than established guidelines support, and these recommendations were strongly correlated with subsequent colonoscopy overuse.

"Our study shows that a high percentage of follow-up colonoscopies are being performed too early, resulting in use of scarce health care resources with potentially limited clinical ...

Chinese scientists unveil liquid phase 3-D printing method using low melting metal alloy ink

2014-09-30

Three-dimensional metal printing technology is an expanding field that has enormous potential applications in areas ranging from supporting structures, functional electronics to medical devices. Conventional 3D metal printing is generally restricted to metals with a high melting point, and the process is rather time consuming.

Now scientists at the Beijing Key Laboratory of CryoBiomedical Engineering, part of the Technical Institute of Physics and Chemistry at the Chinese Academy of Sciences, have developed a new conceptual 3D printing method with "ink" consisting of ...

First dark matter search results from Chinese underground lab hosting PandaX-I experiment

2014-09-30

Scientists across China and the United States collaborating on the PandaX search for dark matter from an underground lab in southwestern China report results from the first stage of the experiment in a new study published in the Beijing-based journal SCIENCE CHINA Physics, Mechanics & Astronomy.

PandaX is the first dark matter experiment in China that deploys more than one hundred kilograms of xenon as a detector; the project is designed to monitor potential collisions between xenon nucleons and weakly interactive massive particles, hypothesized candidates for dark matter.

In ...

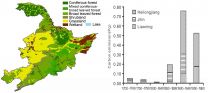

New estimates on carbon emissions triggered by 300 years of cropland expansion in Northeast China

2014-09-30

The conversion of forests, grasslands, shrublands and wetlands to cropland over the course of three centuries profoundly changed the surface of the Earth and the carbon cycle of the terrestrial ecosystem in Northeast China.

In a new study published in the Beijing-based journal SCIENCE CHINA Earth Sciences, a team of researchers from Beijing Normal University, Nanjing University of Information Science & Technology, and the Institute of Geographic Sciences and Natural Resources Research of the Chinese Academy of Sciences, present new calculations on carbon emissions triggered ...