(Press-News.org) Montréal, October 2, 2014 – Scientists at the IRCM discovered a mechanism that promotes the progression of medulloblastoma, the most common brain tumour found in children. The team, led by Frédéric Charron, PhD, found that a protein known as Sonic Hedgehog induces DNA damage, which causes the cancer to develop. This important breakthrough will be published in the October 13 issue of the prestigious scientific journal Developmental Cell. The editors also selected the article to be featured on the journal's cover.

Sonic Hedgehog belongs to a family of proteins that gives cells the information needed for the embryo to develop properly. It also plays a significant role in tumorigenesis, the process that transforms normal cells into cancer cells.

"Our team studied a protein called Boc, which is a receptor located on the cell surface that detects Sonic Hedgehog," explains Lukas Tamayo-Orrego, PhD student in Dr. Charron's laboratory and co-first author of the study. "We had previously shown that Boc is important for the development of the cerebellum, the part of the brain where medulloblastoma arises, so we decided to further investigate its role."

"With this study, we found that the presence of Boc is required for Sonic Hedgehog to induce DNA damage," adds Dr. Charron, Director of the Molecular Biology of Neural Development research unit at the IRCM. "In fact, Boc causes DNA mutations in tumour cells, which promotes the progression of precancerous lesions into advanced medulloblastoma."

"Our study shows that when Boc is inactivated, the number of tumours is reduced by 66 per cent," says Frederic Mille, PhD, co-first author of the article and former postdoctoral fellow in Dr. Charron's research unit. "The inactivation of Boc therefore reduces the development of early medulloblastoma into advanced tumours."

Medulloblastoma ranks among the leading causes of cancer-related mortality in children. Current treatments include surgery, as well as radiation therapy and chemotherapy. Although the majority of children survive the treatment, radiation therapy damages normal brain cells in infants and toddlers and causes long-term harm.

"As a result, many children who undergo these treatments suffer serious side effects including cognitive impairment and disorders," states Dr. Charron. "Our results indicate that Boc could potentially be targeted to develop a new therapeutic approach that would stop the growth and progression of medulloblastoma and could reduce the adverse side effects of current treatments."

INFORMATION:

About the research project

This research project was supported by grants from the Canadian Institutes of Health Research, the Canadian Cancer Society and the Cancer Research Society. Other authors from the IRCM include Martin Lévesque (co-first author), Julie Cardin, Nicolas Bouchard, and Luisa Izzi. The project was also conducted in collaboration with the laboratories of Stefan Pfister in Heidelberg, Germany, and Michael Taylor in Toronto. For more information, please refer to the article summary published online by Developmental Cell: http://www.cell.com/developmental-cell/abstract/S1534-5807(14)00520-6.

About Frédéric Charron

Frédéric Charron obtained his PhD in experimental medicine from McGill University. He is an Associate IRCM Research Professor and Director of the Molecular Biology of Neural Development research unit. Dr. Charron is Associate Research Professor in the Department of Medicine (accreditation in molecular biology) and Adjunct Member in the Department of Neuroscience at the Université de Montréal. He is also Adjunct Professor in the Department of Medicine (Division of Experimental Medicine), the Department of Biology, and the Department of Anatomy and Cell Biology at McGill University. In addition, he is a member of the McGill Integrated Program in Neuroscience, the Montreal Regional Brain Tumor Research Group at the Montreal Neurological Institute, and the Centre of Excellence in Neurosciences (CENUM) at the Université de Montréal. Dr. Charron is a Senior Research Scholar from the Fonds de recherche du Québec – Santé (FRQS). For more information, visit http://www.ircm.qc.ca/charronlab.

About the IRCM

The IRCM is a renowned biomedical research institute located in the heart of Montréal's university district. Founded in 1967, it is currently comprised of 35 research units and four specialized research clinics (cholesterol, cystic fibrosis, diabetes and obesity, hypertension). The IRCM is affiliated with the Université de Montréal, and the IRCM Clinic is associated to the Centre hospitalier de l'Université de Montréal (CHUM). It also maintains a long-standing association with McGill University. The IRCM is funded by the Quebec ministry of Economy, Innovation and Export Trade (Ministère de l'Économie, de l'Innovation et des Exportations).

CHAMPAIGN, Ill. — The big-headed ant (Pheidole megacephala) is considered one of the world's worst invasive ant species. As the name implies, its colonies include soldier ants with disproportionately large heads. Their giant, muscle-bound noggins power their biting parts, the mandibles, which they use to attack other ants and cut up prey. In a new study, researchers report that big-headed ant colonies produce larger soldiers when they encounter other ants that know how to fight back.

The new findings appear in the Biological Journal of the Linnean Society.

Big-headed ...

London, United Kingdom, October 2, 2014 – Despite decades of research, scientists have yet to pinpoint the exact cause of nodding syndrome (NS), a disabling disease affecting African children. A new report suggests that blackflies infected with the parasite Onchocerca volvulus may be capable of passing on a secondary pathogen that is to blame for the spread of the disease. New research is presented in the International Journal of Infectious Diseases.

Concentrated in South Sudan, Northern Uganda, and Tanzania, NS is a debilitating and deadly disease that affects young ...

A new study published in the Cell Press journal Current Biology on October 2 could rewrite the story of ape and human brain evolution. While the neocortex of the brain has been called "the crowning achievement of evolution and the biological substrate of human mental prowess," newly reported evolutionary rate comparisons show that the cerebellum expanded up to six times faster than anticipated throughout the evolution of apes, including humans.

The findings suggest that technical intelligence was likely at least as important as social intelligence in human cognitive ...

The more curious we are about a topic, the easier it is to learn information about that topic. New research publishing online October 2 in the Cell Press journal Neuron provides insights into what happens in our brains when curiosity is piqued. The findings could help scientists find ways to enhance overall learning and memory in both healthy individuals and those with neurological conditions.

"Our findings potentially have far-reaching implications for the public because they reveal insights into how a form of intrinsic motivation—curiosity—affects memory. These findings ...

This release is available in Japanese.

A University of Tokyo research group has discovered that AIM (Apoptosis Inhibitor of Macrophage), a protein that plays a preventive role in obesity progression, can also prevent tumor development in mice liver cells. This discovery may lead to a therapy for hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC), the most common type of liver cancer and the third most common cause of cancer deaths.

Professor Toru Miyazaki's group at the Laboratory of Molecular Biomedicine from Pathogenesis, in the Faculty of Medicine has shown that AIM (also known ...

LA JOLLA, CA—October 2, 2014—Scientists at The Scripps Research Institute (TSRI) have found that an enzyme best known for its fundamental role in building proteins has a second major function: to protect DNA during times of cellular stress.

The finding is remarkable on a basic science level but also points the way to possible therapeutic applications. Strategies that enhance the DNA-protection function of the enzyme, TyrRS, could help protect people from radiation injuries as well as from hereditary defects in DNA repair systems.

"We overexpressed TyrRS in zebrafish ...

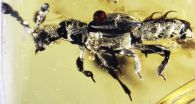

Scientists have uncovered the fossil of a 52-million-year old beetle that likely was able to live alongside ants—preying on their eggs and usurping resources—within the comfort of their nest. The fossil, encased in a piece of amber from India, is the oldest-known example of this kind of social parasitism, known as "myrmecophily." Published today in the journal Current Biology, the research also shows that the diversification of these stealth beetles, which infiltrate ant nests around the world today, correlates with the ecological rise of modern ants.

"Although ants ...

Our immune system must distinguish between self and foreign and in order to fight infections without damaging the body's own cells at the same time. The immune system is loyal to cells in the body, but how this works is not fully understood. Researchers in the Departments of Biomedicine and Nephrology at the University Hospital and the University of Basel have discovered that the immune system uses a molecular biological clock to target intolerant T cells during their maturation process. These recent findings have been reported in the scientific journal Cell.

A functioning ...

It's an early lesson in genetics: we get half our DNA from Mom, half from Dad.

But that straightforward explanation does not account for a process that sometimes occurs when cells divide. Called gene conversion, the copy of a gene from Mom can replace the one from Dad, or vice versa, making the two copies identical.

In a new study published in the American Journal of Human Genetics, University of Pennsylvania researchers Joseph Lachance and Sarah A. Tishkoff investigated this process in the context of the evolution of human populations. They found that a bias toward ...

Scientists love acronyms.

In the quest to solve cancer's mysteries, they come in handy when describing tongue-twisting processes and pathways that somehow allow tumors to form and thrive. Two examples are ERK (extracellular-signal-related kinase) and JNK (c-June N-Terminal Kinase), enzymes that may offer unexpected solutions for treating some endometrial and colon cancers.

A study led by Gordon Mills, M.D., Ph.D., professor and chair of Systems Biology at The University of Texas MD Anderson Cancer Center with Lydia Cheung, Ph.D. as the first author, points to cellular ...