(Press-News.org) New York, NY—October 15, 2014—Researchers from Columbia Engineering and the Georgia Institute of Technology report today that they have made the first experimental observation of piezoelectricity and the piezotronic effect in an atomically thin material, molybdenum disulfide (MoS2), resulting in a unique electric generator and mechanosensation devices that are optically transparent, extremely light, and very bendable and stretchable.

In a paper published online October 15, 2014, in Nature, research groups from the two institutions demonstrate the mechanical generation of electricity from the two-dimensional (2D) MoS2 material. The piezoelectric effect in this material had previously been predicted theoretically.

Piezoelectricity is a well-known effect in which stretching or compressing a material causes it to generate an electrical voltage (or the reverse, in which an applied voltage causes it to expand or contract). But for materials of only a few atomic thicknesses, no experimental observation of piezoelectricity has been made, until now. The observation reported today provides a new property for two-dimensional materials such as molybdenum disulfide, opening the potential for new types of mechanically controlled electronic devices.

"This material—just a single layer of atoms—could be made as a wearable device, perhaps integrated into clothing, to convert energy from your body movement to electricity and power wearable sensors or medical devices, or perhaps supply enough energy to charge your cell phone in your pocket," says James Hone, professor of mechanical engineering at Columbia and co-leader of the research.

"Proof of the piezoelectric effect and piezotronic effect adds new functionalities to these two-dimensional materials," says Zhong Lin Wang, Regents' Professor in Georgia Tech's School of Materials Science and Engineering and a co-leader of the research. "The materials community is excited about molybdenum disulfide, and demonstrating the piezoelectric effect in it adds a new facet to the material."

Hone and his research group demonstrated in 2008 that graphene, a 2D form of carbon, is the strongest material. He and Lei Wang, a postdoctoral fellow in Hone's group, have been actively exploring the novel properties of 2D materials like graphene and MoS2 as they are stretched and compressed.

Zhong Lin Wang and his research group pioneered the field of piezoelectric nanogenerators for converting mechanical energy into electricity. He and postdoctoral fellow Wenzhuo Wu are also developing piezotronic devices, which use piezoelectric charges to control the flow of current through the material just as gate voltages do in conventional three-terminal transistors.

There are two keys to using molybdenum disulfide for generating current: using an odd number of layers and flexing it in the proper direction. The material is highly polar, but, Zhong Lin Wang notes, so an even number of layers cancels out the piezoelectric effect. The material's crystalline structure also is piezoelectric in only certain crystalline orientations.

For the Nature study, Hone's team placed thin flakes of MoS2 on flexible plastic substrates and determined how their crystal lattices were oriented using optical techniques. They then patterned metal electrodes onto the flakes. In research done at Georgia Tech, Wang's group installed measurement electrodes on samples provided by Hone's group, then measured current flows as the samples were mechanically deformed. They monitored the conversion of mechanical to electrical energy, and observed voltage and current outputs.

The researchers also noted that the output voltage reversed sign when they changed the direction of applied strain, and that it disappeared in samples with an even number of atomic layers, confirming theoretical predictions published last year. The presence of piezotronic effect in odd layer MoS2 was also observed for the first time.

"What's really interesting is we've now found that a material like MoS2, which is not piezoelectric in bulk form, can become piezoelectric when it is thinned down to a single atomic layer," says Lei Wang.

To be piezoelectric, a material must break central symmetry. A single atomic layer of MoS2 has such a structure, and should be piezoelectric. However, in bulk MoS2, successive layers are oriented in opposite directions, and generate positive and negative voltages that cancel each other out and give zero net piezoelectric effect.

"This adds another member to the family of piezoelectric materials for functional devices," says Wenzhuo Wu.

In fact, MoS2 is just one of a group of 2D semiconducting materials known as transition metal dichalcogenides, all of which are predicted to have similar piezoelectric properties. These are part of an even larger family of 2D materials whose piezoelectric materials remain unexplored. Importantly, as has been shown by Hone and his colleagues, 2D materials can be stretched much farther than conventional materials, particularly traditional ceramic piezoelectrics, which are quite brittle.

The research could open the door to development of new applications for the material and its unique properties.

"This is the first experimental work in this area and is an elegant example of how the world becomes different when the size of material shrinks to the scale of a single atom," Hone adds. "With what we're learning, we're eager to build useful devices for all kinds of applications."

Ultimately, Zhong Lin Wang notes, the research could lead to complete atomic-thick nanosystems that are self-powered by harvesting mechanical energy from the environment. This study also reveals the piezotronic effect in two-dimensional materials for the first time, which greatly expands the application of layered materials for human-machine interfacing, robotics, MEMS, and active flexible electronics.

INFORMATION:

For this study, the research team also worked with Tony Heinz, David M. Rickey Professor of Optical Communications at Columbia Engineering and professor of physics at Columbia's Graduate School of Arts and Sciences.

The study was supported by the U.S. Department of Energy (DOE), Office of Basic Energy Sciences (BES) (No. DE-FG02-07ER46394) and U.S. National Science Foundation (DMR-1122594).

Media contacts:

Holly Evarts, Director of Strategic Communications and Media Relations, Columbia Engineering

212-854-3206 (o); 347-453-7408 (c), holly.evarts@columbia.edu

John Toon, Director of Research News, Georgia Institute of Technology

404-894-6986; john.toon@comm.gatech.edu

Researchers develop world's thinnest electric generator

First experimental observation of piezoelectricity in an atomically thin material -- MoS2 -- could lead to wearable devices

2014-10-15

ELSE PRESS RELEASES FROM THIS DATE:

UNC researchers boost the heart's natural ability to recover after heart attack

2014-10-15

CHAPEL HILL – Researchers from the UNC School of Medicine have discovered that cells called fibroblasts, which normally give rise to scar tissue after a heart attack, can be turned into endothelial cells, which generate blood vessels to supply oxygen and nutrients to the injured regions of the heart, thus greatly reducing the damage done following heart attack.

This switch is driven by p53, the well-documented tumor-suppressing protein. The UNC researchers showed that increasing the level of p53 in scar-forming cells significantly reduced scarring and improved heart ...

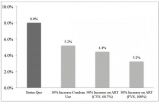

Post-tonsillectomy complications more likely in kids from lower-income families

2014-10-15

Removing a child's tonsils is one of the most common surgeries performed in the United States, with approximately 500,000 children undergoing the procedure each year. New research finds that children from lower-income families are more likely to have complications following the surgery.

In the first study of its kind to analyze post-operative complications requiring a doctor's visit within the first 14 days after tonsillectomy, researchers saw a significant disparity based on income status, race and ethnicity.

"Surprisingly, despite all children having a relatively ...

Tuning light to kill deep cancer tumors

2014-10-15

WORCESTER, MA – An international group of scientists led by Gang Han, PhD, at the University of Massachusetts Medical School, has combined a new type of nanoparticle with an FDA-approved photodynamic therapy to effectively kill deep-set cancer cells in vivo with minimal damage to surrounding tissue and fewer side effects than chemotherapy. This promising new treatment strategy could expand the current use of photodynamic therapies to access deep-set cancer tumors.

"We are very excited at the potential for clinical practice using our enhanced red-emission nanoparticles ...

Discovery of a new mechanism that can lead to blindness

2014-10-15

Montréal, October 15, 2014 – An important scientific breakthrough by a team of IRCM researchers led by Michel Cayouette, PhD, is being published today by The Journal of Neuroscience. The Montréal scientists discovered that a protein found in the retina plays an essential role in the function and survival of light-sensing cells that are required for vision. These findings could have a significant impact on our understanding of retinal degenerative diseases that cause blindness.

The researchers studied a process called compartmentalization, which establishes ...

Blinded by science

2014-10-15

Do you believe in science? Your faith in science may actually make you more likely to trust information that appears scientific but really doesn't tell you much. According to a new Cornell Food and Brand Lab study, published in Public Understanding of Science, trivial elements such as graphs or formulas can lead consumers to believe products are more effective. "Anything that looks scientific can make information you read a lot more convincing," says the study's lead author Aner Tal, PhD, "The scientific halo of graphs, formulas, and other trivial elements that look scientific ...

Weather history time machine

2014-10-15

During the 1930s, North America endured the Dust Bowl, a prolonged era of dryness that withered crops and dramatically altered where the population settled. Land-based precipitation records from the years leading up to the Dust Bowl are consistent with the telltale drying-out period associated with a persistent dry weather pattern, but they can't explain why the drought was so pronounced and long-lasting.

The mystery lies in the fact that land-based precipitation tells only part of the climate story. Building accurate computer reconstructions of historical global precipitation ...

Change your walking style, change your mood

2014-10-15

Our mood can affect how we walk — slump-shouldered if we're sad, bouncing along if we're happy. Now researchers have shown it works the other way too — making people imitate a happy or sad way of walking actually affects their mood.

Subjects who were prompted to walk in a more depressed style, with less arm movement and their shoulders rolled forward, experienced worse moods than those who were induced to walk in a happier style, according to the study published in the Journal of Behavior Therapy and Experimental Psychiatry.

CIFAR Senior Fellow Nikolaus ...

New guideline in genetic testing for certain types of muscular dystrophy

2014-10-15

Rochester, Minn. – The American Academy of Neurology (AAN) and the American Association of Neuromuscular & Electrodiagnostic Medicine (AANEM) offer a new guideline on how to determine what genetic tests may best diagnose a person's subtype of limb-girdle or distal muscular dystrophy. The guideline is published in the October 14, 2014, print issue of Neurology®, the medical journal of the AAN.

Researchers reviewed all of the available studies on the muscular dystrophy, a group of genetic diseases in which muscle fibers are unusually susceptible to damage, as ...

Eating breakfast increases brain chemical involved in regulating food intake and cravings

2014-10-15

COLUMBIA, Mo. – According to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), many teens skip breakfast, which increases their likelihood of overeating and eventual weight gain. Statistics show that the number of adolescents struggling with obesity, which elevates the risk for chronic health problems, has quadrupled in the past three decades. Now, MU researchers have found that eating breakfast, particularly meals rich in protein, increases young adults' levels of a brain chemical associated with feelings of reward, which may reduce food cravings and overeating ...

Study models ways to cut Mexico's HIV rates

2014-10-15

PROVIDENCE, R.I. [Brown University] — To address the HIV epidemic in Mexico is to address it among men who have sex with men (MSM), because they account for a large percentage of the country's new infections, says Omar Galárraga, assistant professor of health services policy and practice in the Brown University School of Public Health.

A major source of the new infections is Mexico City's male-to-male sex trade, Galárraga has found. In his research, including detailed interviews and testing with hundreds of male sex workers on the city's streets and in ...

LAST 30 PRESS RELEASES:

Racial, political cues on social media shape TV audiences’ choices

New model offers ‘clear path’ to keeping clean water flowing in rural Africa

Ochsner MD Anderson to be first in the southern U.S. to offer precision cancer radiation treatment

Newly transferred jumping genes drive lethal mutations

Where wells run deep, biodiversity runs thin

Q&A: Gassing up bioengineered materials for wound healing

From genetics to AI: Integrated approaches to decoding human language in the brain

Leora Westbrook appointed executive director of NR2F1 Foundation

Massive-scale spatial multiplexing with 3D-printed photonic lanterns achieved by researchers

Younger stroke survivors face greater concentration, mental health challenges — especially those not employed

From chatbots to assembly lines: the impact of AI on workplace safety

Low testosterone levels may be associated with increased risk of prostate cancer progression during surveillance

Analysis of ancient parrot DNA reveals sophisticated, long-distance animal trade network that pre-dates the Inca Empire

How does snow gather on a roof?

Modeling how pollen flows through urban areas

Blood test predicts dementia in women as many as 25 years before symptoms begin

Female reproductive cancers and the sex gap in survival

GLP-1RA switching and treatment persistence in adults without diabetes

Gnaw-y by nature: Researchers discover neural circuit that rewards gnawing behavior in rodents

Research alert: How one receptor can help — or hurt — your blood vessels

Lamprey-inspired amphibious suction disc with hybrid adhesion mechanism

A domain generalization method for EEG based on domain-invariant feature and data augmentation

Bionic wearable ECG with multimodal large language models: coherent temporal modeling for early ischemia warning and reperfusion risk stratification

JMIR Publications partners with the University of Turku for unlimited OA publishing

Strange cosmic burst from colliding galaxies shines light on heavy elements

Press program now available for the world's largest physics meeting

New release: Wiley’s Mass Spectra of Designer Drugs 2026 expands coverage of emerging novel psychoactive substances

Exposure to life-limiting heat has soared around the planet

New AI agent could transform how scientists study weather and climate

New study sheds light on protein landscape crucial for plant life

[Press-News.org] Researchers develop world's thinnest electric generatorFirst experimental observation of piezoelectricity in an atomically thin material -- MoS2 -- could lead to wearable devices