(Press-News.org) STANFORD, Calif. — Despite concerted efforts, no decreases in patient harm were detected at 10 randomly selected North Carolina hospitals between 2002 and 2007, according to a new study from the Stanford University School of Medicine, Harvard Medical School and the Institute for Healthcare Improvement.

Since a 1999 Institute of Medicine report sounded the alarm about high medical error rates, most U.S. hospitals have changed their operations to keep patients safer. The researchers wanted to assess whether these patient-safety efforts reduced harm. They studied hospitals in North Carolina because that state has shown a particularly strong commitment to patient safety.

"We found that harm rates — in a state that was very engaged in patient safety — did not change over time. This was a little surprising to all of us," said senior study author Paul Sharek, MD, who is an associate professor of pediatrics at Stanford and chief clinical patient safety officer at Lucile Packard Children's Hospital. "Our findings are a call to action for the health-care system. We need a nationwide strategy for reducing harm from medical care."

The research will be published Nov. 25 in the New England Journal of Medicine. The study's lead author is Christopher Landrigan, MD, assistant professor of pediatrics and of medicine at Harvard.

To perform the study, the team first verified the sensitivity and reliability of the IHI's Global Trigger Tool to detect evidence of harm through a review of patients' medical records. Trained investigators scanned patients' charts for "trigger" events that suggested harm had occurred. For instance, a prescription for the anti-opioid drug naloxone could suggest an overdose of morphine or a related opioid medication. When reviewers found such an event, they performed a close reading of the patient's entire medical record to look for evidence of harm.

In the study, teams of reviewers drawn from within and outside the study hospitals used this method to examine medical charts from 2,341 randomly selected hospital admissions at 10 randomly selected hospitals in North Carolina between January 2002 and December 2007.

The reviewers found evidence of 588 instances of harm to patients. More than 80 percent of the harms identified were temporary. About half of the temporary harms prolonged the patient's hospital stay; the remaining temporary harms required intervention but did not increase hospital length of stay.

"As had been shown in several other studies, the great majority of medically induced harms in inpatient settings are minor or reversible," said Sharek. But, consistent with other research, some patients did have more serious harms: 50 were classified as life-threatening, 17 incidents resulted in permanent harm to a patient and 14 deaths were attributed in whole or in part to medical errors.

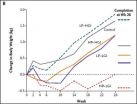

Total harm rates remained the same throughout the study, at about 25 harms per 100 hospital admissions. Separate analysis of different types of harms — more vs. less severe and preventable vs. non-preventable — did not uncover any subtypes of harm that changed during the study. However, the study did not have the statistical power to evaluate changes in the rate of the most serious harms.

There are several possible explanations as to why harm rates did not improve over time despite active engagement in patient-safety efforts in hospitals across North Carolina, the authors noted.

First, "Implementation of best practices shown to improve patient safety is very difficult and takes time," Sharek said. "The 10 hospitals involved in this study have likely implemented a number of best practices related to patient safety, but, at least by 2007, had not yet reaped the benefit of this hard work. Our study should not be interpreted to mean that North Carolina's vigorous safety efforts have not had an effect since 2007."

Second, several of the practices shown in prior research to improve patient safety — such as the use of electronic medical records, computerized physician work-order entry and work-hour limits for medical staff — take time and often substantial funding to fully implement.

Third, the science of patient safety is relatively young and thus there are few evidence-based best practices identified in the medical literature for hospitals to implement. As a result, many practices that could theoretically improve patient safety are being tried by well-intentioned health-care providers without evidence that these actually reduce patient harm. More research is needed to separate useful safety interventions from those that do not reduce medical errors, Sharek said.

###The research was funded by a grant from the Rx Foundation and by funds from the Institute for Healthcare Improvement.

The Stanford University School of Medicine consistently ranks among the nation's top medical schools, integrating research, medical education, patient care and community service. For more news about the school, please visit http://mednews.stanford.edu. The medical school is part of Stanford Medicine, which includes Stanford Hospital & Clinics and Lucile Packard Children's Hospital. For information about all three, please visit http://stanfordmedicine.org/about/news.html.

Celebrating its 20th anniversary in 2011, Lucile Packard Children's Hospital is annually ranked as one of the nation's best pediatric hospitals by U.S. News & World Report, and is the only San Francisco Bay Area children's hospital with programs ranked in the U.S. News Top Ten. The 311-bed hospital is devoted to the care of children and expectant mothers, and provides pediatric and obstetric medical and surgical services in association with the Stanford University School of Medicine. Packard Children's offers patients locally, regionally and nationally a full range of health-care programs and services, from preventive and routine care to the diagnosis and treatment of serious illness and injury. For more information, visit www.lpch.org.

END

The new results, from a team led by Grzegorz Pietrzyński (Universidad de Concepción, Chile, Obserwatorium Astronomiczne Uniwersytetu Warszawskiego, Poland), appear in the 25 November 2010 edition of the journal Nature.

Grzegorz Pietrzyński introduces this remarkable result: "By using the HARPS instrument on the 3.6-metre telescope at ESO's La Silla Observatory in Chile, along with other telescopes, we have measured the mass of a Cepheid with an accuracy far greater than any earlier estimates. This new result allows us to immediately see which of the two competing ...

By cooling Rubidium atoms deeply and concentrating a sufficient number of them in a compact space, they suddenly become indistinguishable. They behave like a single huge "super particle." Physicists call this a Bose-Einstein condensate.

For "light particles," or photons, this should also work. Unfortunately, this idea faces a fundamental problem. When photons are "cooled down," they disappear. Until a few months ago, it seemed impossible to cool light while concentrating it at the same time. The Bonn physicists Jan Klärs, Julian Schmitt, Dr. Frank Vewinger, and Professor ...

MEDFORD/SOMERVILLE, Mass. -- Researchers at Tufts University School of Engineering have reported the first successful production of the antibiotic erythromycin A, and two variations, using E. coli as the production host.

The work, published in the November 24, 2010, issue of Chemistry and Biology, offers a more cost-effective way to make both erythromycin A and new drugs that will combat the growing incidence of antibiotic resistant pathogens. Equally important, the E. coli production platform offers numerous next-generation engineering opportunities for other natural ...

Palo Alto, CA— Infestation by bacteria and other pathogens result in global crop losses of over $500 billion annually. A research team led by the Carnegie Institution's Department of Plant Biology developed a novel trick for identifying how pathogens hijack plant nutrients to take over the organism. They discovered a novel family of pores that transport sugar out of the plant. Bacteria and fungi hijack the pores to access the plant sugar for food. The first goal of any pathogen is to access the host's food supply to allow them to reproduce in large numbers. This is the ...

Researchers with UCLA's Jonsson Comprehensive Cancer Center have found that melanoma patients whose cancers are caused by mutation of the BRAF gene become resistant to a promising targeted treatment through another genetic mutation or the overexpression of a cell surface protein, both driving survival of the cancer and accounting for relapse.

The study, published Nov. 24, 2010, in the early online edition of the peer-reviewed journal Nature, could result in the development of new targeted therapies to fight resistance once the patient stops responding and the cancer ...

The past year has brought to light both the promise and the frustration of developing new drugs to treat melanoma, the most deadly form of skin cancer. Early clinical tests of a candidate drug aimed at a crucial cancer-causing gene revealed impressive results in patients whose cancers resisted all currently available treatments. Unfortunately, those effects proved short-lived, as the tumors invariably returned a few months later, able to withstand the same drug to which they first succumbed. Adding to the disappointment, the reasons behind these relapses were unclear.

Now, ...

Researchers appear to have an explanation for a longstanding question in HIV biology: how it is that the virus kills so many CD4 T cells, despite the fact that most of them appear to be "bystander" cells that are themselves not productively infected. That loss of CD4 T cells marks the progression from HIV infection to full-blown AIDS, explain the researchers who report their findings in studies of human tonsils and spleens in the November 24th issue of Cell, a Cell Press publication.

"In [infected] primary human tonsils and spleens, there is a profound depletion of CD4 ...

Researchers at the Faculty of Life Sciences (LIFE), University of Copenhagen, can now unveil the results of the world's largest diet study:

If you want to lose weight, you should maintain a diet that is high in proteins with more lean meat, low-fat dairy products and beans and fewer finely refined starch calories such as white bread and white rice. With this diet, you can also eat until you are full without counting calories and without gaining weight. Finally, the extensive study concludes that the official dietary recommendations are not sufficient for preventing obesity. ...

They are the largest fish species in the ocean, but the majestic gliding motion of the whale shark is, scientists argue, an astonishing feat of mathematics and energy conservation. In new research published today in the British Ecological Society's journal Functional Ecology marine scientists reveal how these massive sharks use geometry to enhance their natural negative buoyancy and stay afloat.

For most animals movement is crucial for survival, both for finding food and for evading predators. However, movement costs substantial amounts of energy and while this is true ...

An international team led by researchers from the Universities of Leicester and Cambridge has announced a breakthrough in identifying people at risk of developing potentially fatal blood clots that can lead to heart attack.

The discovery, published this week (25 November) in the leading haematology journal Blood, is expected to advance ways of detecting and treating coronary heart disease – the most common form of disease affecting the heart and an important cause of premature death.

The research led by Professor Alison Goodall from the University of Leicester and Professor ...