Most published medical research is false; Here's how to improve

2014-10-21

(Press-News.org) In 2005, in a landmark paper viewed well over a million times, John Ioannidis explained in PLOS Medicine why most published research findings are false. To coincide with PLOS Medicine's 10th anniversary he responds to the challenge of this situation by suggesting how the research enterprise could be improved.

Research, including medical research, is subject to a range of biases which mean that misleading or useless work is sometimes pursued and published while work of value is ignored. The risks and rewards of academic careers, the structures and habits of peer reviewed journals, and the way universities and research institutions are set up and governed all have profound effects on what research scientists undertake, how they choose to do it and, ultimately, how patients are treated. Perverse incentives can lead scientists to waste time producing and publishing results which are wrong or useless. Understanding these incentives and altering them provides a potential way for drastically re-shaping research to improve in medical knowledge.

In a provocative and personal essay, designed to spur readers into thinking about how research careers could be redesigned in order to encourage better work, Ioannidis suggests practical ways in which our current situation could be improved. He describes how successful practices from some branches of science could be distributed to others which have performed badly, and suggests ways in which academic structures could provide greater benefits from the work of researchers, administrators, publishers and the research funding which supports them all.

"The achievements of science are amazing yet the majority of research effort is currently wasted," asserts Ioannidis. He calls for testing interventions to improve the structure of scientific research, and doing so with the rigor normally reserved for testing drugs or hypotheses.

INFORMATION:

ELSE PRESS RELEASES FROM THIS DATE:

2014-10-21

Cesarean delivery is the most common inpatient surgery in the United States. US cesarean rates increased from 20.7% in 1996 to 32.9% in 2009 but have since stabilized, with 1.3 million American women having had a cesarean delivery in 2011. Rates of cesarean delivery vary across hospitals, and understanding reasons for the variation could help shed light on practices related to cesarean delivery.

Katy Kozhimannil (University of Minnesota School of Public Health, Minneapolis, USA) and colleagues S.V. Subramanian and Mariana Arcaya (Harvard School of Public Health, Boston, ...

2014-10-21

personalised nutrition based on an individual's genotype - nutrigenomics - could have a major impact on reducing lifestyle-linked diseases such as obesity, heart disease and Type II diabetes

a study of more than 9,000 volunteers reveals strict regulations need to be put in place before nutrigenomics becomes publicly acceptable due to people's fears around personal data protection

led by Newcastle University, UK, and involving experts from the universities of Ulster, Bradford, Porto (Portugal) and Wageningen (Netherlands), the study is the first to assess consumer acceptance ...

2014-10-21

EUGENE, Ore. -- Oct. 21, 2014 -- University of Oregon chemists have devised a way to see the internal structures of electronic waves trapped in carbon nanotubes by external electrostatic charges.

Carbon nanotubes have been touted as exceptional materials with unique properties that allow for extremely efficient charge and energy transport, with the potential to open the way for new, more efficient types of electronic and photovoltaic devices. However, these traps, or defects, in ultra-thin nanotubes can compromise their effectiveness.

Using a specially built microscope ...

2014-10-21

MADISON, Wis. — As Dane County begins the long slide into winter and the days become frostier this fall, three spots stake their claim as the chilliest in the area.

One is a cornfield in a broad valley and two are wetlands. In contrast, the isthmus makes an island — an urban heat island.

In a new study published this month in the Journal of Applied Meteorology and Climatology, University of Wisconsin-Madison researchers highlight the urban heat island effect in Madison: The city's concentrated asphalt, brick and concrete lead to higher temperatures than ...

2014-10-21

BETHESDA, MD – Age-related loss of the Y chromosome (LOY) from blood cells, a frequent occurrence among elderly men, is associated with elevated risk of various cancers and earlier death, according to research presented at the American Society of Human Genetics (ASHG) 2014 Annual Meeting in San Diego.

This finding could help explain why men tend to have a shorter life span and higher rates of sex-unspecific cancers than women, who do not have a Y chromosome, said Lars Forsberg, PhD, lead author of the study and a geneticist at Uppsala University in Sweden.

LOY, ...

2014-10-21

(Philadelphia, PA) – Chest pain doesn't necessarily come from the heart. An estimated 200,000 Americans each year experience non-cardiac chest pain, which in addition to pain can involve painful swallowing, discomfort and anxiety. Non-cardiac chest pain can be frightening for patients and result in visits to the emergency room because the painful symptoms, while often originating in the esophagus, can mimic a heart attack. Current treatment — which includes pain modulators such as selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRI) — has a partial 40 to 50 ...

2014-10-21

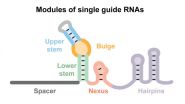

Customized genome editing – the ability to edit desired DNA sequences to add, delete, activate or suppress specific genes – has major potential for application in medicine, biotechnology, food and agriculture.

Now, in a paper published in Molecular Cell, North Carolina State University researchers and colleagues examine six key molecular elements that help drive this genome editing system, which is known as CRISPR-Cas.

NC State's Dr. Rodolphe Barrangou, an associate professor of food, bioprocessing and nutrition sciences, and Dr. Chase Beisel, an assistant ...

2014-10-21

A longstanding question among scientists is whether evolution is predictable. A team of researchers from UC Santa Barbara may have found a preliminary answer. The genetic underpinnings of complex traits in cephalopods may in fact be predictable because they evolved in the same way in two distinct species of squid.

Last, year, UCSB professor Todd Oakley and then-Ph.D. student Sabrina Pankey profiled bioluminescent organs in two species of squid and found that while they evolved separately, they did so in a remarkably similar manner. Their findings are published today in ...

2014-10-21

Research in recent years has shown that people associate specific facial traits with an individual's personality. For instance, people consistently rate faces that appear more feminine or that naturally appear happy as looking more trustworthy. In addition to trustworthiness, people also consistently associate competence, dominance, and friendliness with specific facial traits. According to an article published by Cell Press on October 21st in Trends in Cognitive Sciences, people rely on these subtle and arbitrary facial traits to make important decisions, from voting for ...

2014-10-21

(SALT LAKE CITY)—Workers punching in for the graveyard shift may be better off not eating high-iron foods at night so they don't disrupt the circadian clock in their livers.

Disrupted circadian clocks, researchers believe, are the reason that shift workers experience higher incidences of type 2 diabetes, obesity and cancer. The body's primary circadian clock, which regulates sleep and eating, is in the brain. But other body tissues also have circadian clocks, including the liver, which regulates blood glucose levels.

In a new study in Diabetes online, University ...

LAST 30 PRESS RELEASES:

[Press-News.org] Most published medical research is false; Here's how to improve