(Press-News.org) DALLAS - November 11, 2014 - UT Southwestern Medical Center researchers have determined the specific type of cell that gives rise to large, disfiguring tumors called plexiform neurofibromas, a finding that could lead to new therapies for preventing growth of these tumors.

"This advance provides new insight into the steps that lead to tumor development and suggests ways to develop therapies to prevent neurofibroma formation where none exist today," said Dr. Lu Le, Assistant Professor of Dermatology at UT Southwestern and senior author of the study, published online and in Cancer Cell.

Plexiform neurofibromas, which are complex tumors that form around nerves, occur in patients with a genetic disorder called neurofibromatosis type 1 (NF1), which affects 1 in 3,500 people. About 30 percent of NF1 patients develop this type of tumor, which is typically benign.

NF1 patients with plexiform neurofibromas, however, have a 10 percent lifetime risk of the tumors developing into malignant peripheral nerve sheath tumors (MPNSTs), a deadly, incurable type of soft-tissue cancer. In addition, due to their unusual capacity for growth, plexiform neurofibromas can be life-threatening by their physical impairment of vital organs or neural function.

While there are no currently approved therapies for either MPNSTs or plexiform neurofibromas, Dr. Le said determining the cell type and location from which these tumors originate is an important step toward discovering new drugs that inhibit tumor development.

"If we can isolate and grow the cells of origin for neurofibromas, then we can reconstruct the biological steps that lead these original cells to tumor stage," said Dr. Le, a member of the Harold C. Simmons Cancer Center. "Once we know the critical steps in the process, then we can design inhibitors to block each step in an effort to prevent or slow tumor formation."

Using a process called genetic labeling for cell fate tracing, researchers determined that plexiform neurofibromas originate from Schwann cell precursors in embryonic nerve roots.

"This study addresses a fundamental question in the neurofibromatosis field," Dr. Le said. "It points to the importance of stem cells and their immediate progenitors in the initiation of tumors, consistent with the notion that these neoplasms originate in a subset of primitive precursors and that most cells in an organ do not generate tumors."

In a related study published last year, Dr. Le's research team found that inhibiting the action of a protein called BRD4 caused tumors to shrink in a mouse model of MPNST. UT Southwestern is working with a pharmaceutical company to bring a BRD4-inhibiting drug into clinical trials for MPNST patients.

New drugs are desperately needed to treat both MPNST and plexiform neurofibromas, said Dr. Le, who also serves as co-director of UT Southwestern's Comprehensive Neurofibromatosis Clinic. The clinic, co-directed by Dr. Laura Klesse, Assistant Professor of Pediatrics and a Dedman Family Scholar in Clinical Care, is part of the Harold C. Simmons Cancer Center and serves patients with all types of hereditary neurofibromatosis.

INFORMATION:

Other UT Southwestern researchers involved in the Cancer Cell study, all in Dermatology, were first author and postdoctoral researcher Dr. Zhiguo Chen; postdoctoral researchers Drs. Amish Patel and Chung-Ping Liao; and research associate Yong Wang.

The study was funded by UT Southwestern's Disease-Oriented Clinical Scholars Program, the Elisabeth Reed Wagner Fund for Research and Clinical Care in Neurofibromatosis and Cardiothoracic Surgery, the National Cancer Institute, the Children's Tumor Foundation, and the U.S. Department of Defense.

UT Southwestern's Harold C. Simmons Cancer Center is the only National Cancer Institute-designated cancer center in North Texas and one of just 66 NCI-designated cancer centers in the nation. The Harold C. Simmons Cancer Center includes 13 major cancer care programs with a focus on treating the whole patient with innovative treatments, while fostering groundbreaking basic research that has the potential to improve patient care and prevention of cancer worldwide. In addition, the Center's education and training programs support and develop the next generation of cancer researchers and clinicians.

About UT Southwestern Medical Center

UT Southwestern, one of the premier academic medical centers in the nation, integrates pioneering biomedical research with exceptional clinical care and education. The institution's faculty includes many distinguished members, including six who have been awarded Nobel Prizes since 1985. Numbering approximately 2,800, the faculty is responsible for groundbreaking medical advances and is committed to translating science-driven research quickly to new clinical treatments. UT Southwestern physicians provide medical care in 40 specialties to about 92,000 hospitalized patients and oversee approximately 2.1 million outpatient visits a year.

As scientists probe the molecular underpinnings of why some people are prone to obesity and some to leanness, they are discovering that weight maintenance is more complicated than the old "calories in, calories out" adage.

A team of researchers led by the University of Pennsylvania School of Veterinary Medicine's Kendra K. Bence have now drawn connections between known regulators of body mass, pointing to possible treatments for obesity and metabolic disorders.

Their work also presents intriguing clues that these same molecular pathways may play a role in learning ...

Salivary mucins, key components of mucus, actively protect the teeth from the cariogenic bacterium, Streptococcus mutans, according to research published ahead of print in Applied and Environmental Microbiology. The research suggests that bolstering native defenses might be a better way to fight dental caries than relying on exogenous materials, such as sealants and fluoride treatment, says first author Erica Shapiro Frenkel, of Harvard University, Cambridge, MA.

S. mutans attaches to teeth using sticky polymers that it produces, eventually forming a biofilm, a protected ...

From this week's Eos: Scientists Engage With the Public During Lava Flow Threat

On 27 June, lava from Kīlauea, an active volcano on the island of Hawai`i, began flowing to the northeast, threatening the residents in Pāhoa, a community in the District of Puna, as well as the only highway accessible to this area. Scientists from the U.S. Geological Survey's Hawaiian Volcano Observatory (HVO) and the Hawai`i County Civil Defense have been monitoring the volcano's lava flow and communicating with affected residents through public meetings since 24 August. Eos recently ...

The majority of people - including healthcare professionals - are unable to visually identify whether a person is a healthy weight, overweight or obese according to research by psychologists at the University of Liverpool.

Researchers from the University's Institute of Psychology, Health and Society asked participants to look at photographs of male models and categorise whether they were a healthy weight, overweight or obese according to World Health Organisation (WHO) Body Mass Index (BMI) guidelines.

They found that the majority of participants were unable to correctly ...

CHAMPAIGN, Ill. -- Tiny, thin microtubes could provide a scaffold for neuron cultures to grow so that researchers can study neural networks, their growth and repair, yielding insights into treatment for degenerative neurological conditions or restoring nerve connections after injury.

Researchers at the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign and the University of Wisconsin-Madison created the microtube platform to study neuron growth. They posit that the microtubes could one day be implanted like stents to promote neuron regrowth at injury sites or to treat disease.

"This ...

WEST LAFAYETTE, Ind. - Crop producers and scientists hold deeply different views on climate change and its possible causes, a study by Purdue and Iowa State universities shows.

Associate professor of natural resource social science Linda Prokopy and fellow researchers surveyed 6,795 people in the agricultural sector in 2011-2012 to determine their beliefs about climate change and whether variation in the climate is triggered by human activities, natural causes or an equal combination of both.

More than 90 percent of the scientists and climatologists surveyed said they ...

Located hundreds of miles inland from the nearest ocean, the Midwest is unaffected by North Atlantic hurricanes.

Or is it?

With the Nov. 30 end of the 2014 hurricane season just weeks away, a University of Iowa researcher and his colleagues have found that North Atlantic tropical cyclones in fact have a significant effect on the Midwest. Their research appears in the Bulletin of the American Meteorological Society.

Gabriele Villarini, UI assistant professor of civil and environmental engineering, studied the discharge records collected at 3,090 U.S. Geological Survey ...

COLUMBIA, Mo. - Glycogen storage disorders, which affect the body's ability to process sugar and store energy, are rare metabolic conditions that frequently manifest in the first years of life. Often accompanied by liver and muscle disease, this inability to process and store glucose can have many different causes, and can be difficult to diagnose. Now, researchers at the University of Missouri who have studied enzymes involved in metabolism of bacteria and other organisms have catalogued the effects of abnormal enzymes responsible for one type of this disorder in humans. ...

What if you researched your family's genealogy, and a mysterious stranger turned out to be an ancestor?

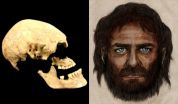

That's the surprising feeling had by a team of scientists who peered back into Europe's murky prehistoric past thousands of years ago. With sophisticated genetic tools, supercomputing simulations and modeling, they traced the origins of modern Europeans to three distinct populations.

The international research team published their September 2014 results in the journal Nature.

XSEDE, the Extreme Science and Engineering Discovery Environment, provided the computational ...

Reston, Va. (November 11, 2014) - A novel study demonstrates the potential of a novel molecular imaging drug to detect and visualize early prostate cancer in soft tissue, lymph nodes and bone. The research, published in the November issue of the Journal of Nuclear Medicine, compares the biodistribution and tumor uptake kinetics of two Tc-99m labeled ligands, MIP-1404 and MIP-1405, used with SPECT and planar imaging.

Prostate cancer is the most commonly diagnosed non-skin cancer in the United States, and it is second only to lung cancer as the leading cause of cancer ...