(Press-News.org) INDIANAPOLIS -- Researchers have identified two proteins that appear crucial to the development -- and patient relapse -- of acute myeloid leukemia. They have also shown they can block the development of leukemia by targeting those proteins.

The studies, in animal models, could lead to new effective treatments for leukemias that are resistant to chemotherapy, said Reuben Kapur, Ph.D., Freida and Albrecht Kipp Professor of Pediatrics at the Indiana University School of Medicine.

The research was reported today in the journal Cell Reports.

"The issue in the field for a long time has been that many patients relapse even though chemotherapy and other currently available drugs get rid of mature blast cells quite readily," Dr. Kapur said, referring to the cancerous cells that overrun the blood system in leukemia.

"The problem is that the majority of patients relapse because they have remaining residual leukemic stem cells in the bone marrow that are resistant to currently available therapies, including chemotherapy," he said.

Mutations in two cellular structures known as receptors have previously been identified as cancer-causing. Patients with those mutations generally have a poor prognosis, but scientists have been uncertain what mechanism led to leukemia in the stem cells with those mutations.

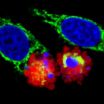

In the Cell Reports paper, Dr. Kapur, first author Anindya Chatterjee, Ph.D., and their colleagues describe the mechanism that leads to the development of acute myeloid leukemia, identifying two proteins known as FAK and PAK1 as key to the process.

In experiments with mice, the researchers showed that eliminating, or "knocking out," the genes that produce FAK and PAK1 prevented the development of leukemia in mice, even though their bone marrow stem cells contained the cancer-causing receptor mutations. Eliminating the FAK and PAK1 proteins did not prevent the mice from otherwise producing and maintaining a normal blood system, the researchers said.

In additional experiments in mice and human cell tissue samples, the researchers identified several drug compounds that target FAK and PAK1 -- now available for experimental use but not approved for use in humans -- that were just as effective in blocking development of leukemia as knocking out the FAK and PAK1 genes.

The next step is to continue testing and refining those experimental drug compounds to verify their effectiveness for potential testing in human trials, Dr. Kapur said.

Dr. Kapur is director of the program in hematologic malignancies and stem cell biology at the Herman B Wells Center for Pediatric Research and an investigator at the Indiana University Melvin and Bren Simon Cancer Center.

INFORMATION:

Other researchers contributing to the work were Joydeep Ghosh, Baskar Ramdas, Raghuveer Singh Mali, Holly Martin, Michihiro Kobayashi, Sasidhar Vemula, Victor H. Canela, Emily R. Waskow, H. Scott Boswell, Yan Liu and Rebecca J. Chan of the IU School of Medicine; Valeria Visconte and Ramon V. Tiu of the Cleveland Clinic; Catherine C. Smith and Neil Shah of the University of California, San Francisco; and Kevin D. Bunting of the Emory University School of Medicine.

The research was supported in part by grants from National Institutes of Health (R01HL077177, R01HL081111, R01CA173852 and R01CA134777), and from the Riley Children's Foundation. Dr. Chatterjee is an American Cancer Society post-doctoral fellow supported by PF13-065-01, and by T32HL007910 from the National Institutes of Health.

Plants all over the world are more sensitive to drought than many experts realized, according to a new study by scientists at UCLA and China's Xishuangbanna Tropical Botanical Garden. The research will improve predictions of which plant species will survive the increasingly intense droughts associated with global climate change.

The research is reported online by Ecology Letters, the most prestigious journal in the field of ecology, and will be published in an upcoming print edition.

Predicting how plants will respond to climate change is crucial for their conservation. ...

MOUNT VERNON, Wash. -- A new study by researchers at Washington State University shows that mechanical harvesting of cider apples can provide labor and cost savings without affecting fruit, juice, or cider quality.

The study, published in the journal HortTechnology in October, is one of several studies focused on cider apple production in Washington State. It was conducted in response to growing demand for hard cider apples in the state and the nation.

Quenching a thirst for cider

Hard cider consumption is trending steeply upward in the region surrounding the food-conscious ...

As our society ages, a University of Montreal study suggests the health system should be focussing on comorbidity and specific types of disabilities that are associated with higher health care costs for seniors, especially cognitive disabilities. Comorbidity is defined as the presence of multiple disabilities. Michaël Boissonneault and Jacques Légaré of the university's Department of Demography came to this conclusion after assessing how individual factors are associated with variation in the public costs of healthcare by studying disabled Quebecers over ...

The scientists showed that the Parkin protein functions to repair or destroy damaged nerve cells, depending on the degree to which they are damaged

People living with Parkinson's disease often have a mutated form of the Parkin gene, which may explain why damaged, dysfunctional nerve cells accumulate

Dublin, Ireland, November 13th, 2014 - Scientists at Trinity College Dublin have made an important breakthrough in our understanding of Parkin - a protein that regulates the repair and replacement of nerve cells within the brain. This breakthrough generates a new perspective ...

There are no approved treatments or preventatives against Ebola virus disease, but investigators have now designed peptides that mimic the virus' N-trimer, a highly conserved region of a protein that's used to gain entry inside cells.

The team showed that the peptides can be used as targets to help researchers develop drugs that might block Ebola virus from entering into cells.

"In contrast to the most promising current approaches for Ebola treatment or prevention, which are species-specific, our 'universal' target will enable the selection of broad-spectrum inhibitors ...

In a study of middle-aged men who were overweight, researchers found that if a man's parents were older at the time of his birth, he was more likely to have lower blood pressure, more favorable cholesterol levels, and improved glucose metabolism. It's unknown whether the beneficial effect was due to having an older mother, an older father, or both.

Additional studies are necessary to help shed light on the effects of parental age at childbirth on the metabolism of men and women. "In particular, more research is required to understand whether these effects are due to ...

In a study that looked at what factors might affect whether or not a patient receives intensive medical procedures in the last 6 months of life, investigators found that older age, Alzheimer's disease, cancer, living in a nursing home, and having an advance directive were associated with a lower likelihood of undergoing an intensive procedure. In contrast, living in a region with higher hospital care intensity and black race each doubled a patient's likelihood of undergoing an intensive procedure.

"It's pretty striking the extent to which nonclinical factors--such as ...

Preeclampsia, a late-pregnancy disorder that is characterized by high blood pressure and organ damage, may be caused by problems related to meeting the oxygen demands of the growing fetus, experts say in a new Anaesthesia paper.

Left untreated, preeclampsia can lead to serious--even fatal--complications for a pregnant woman and her baby. The new theory challenges the current view that pre-eclampsia is caused by a problem with the placenta. "When the fetus is not getting enough oxygen and nutrients for its growth--due to conditions in the mother, conditions in the placenta ...

Investigators recently set out to consider whether homicides involving social networking sites were unique and worthy of labels such as 'Facebook Murder', and to explore the ways in which perpetrators had used such sites in the homicides they had committed.

The cases they identified were not collectively unique or unusual when compared with general trends and characteristics--certainly not to a degree that would necessitate the introduction of a new category of homicide or a broad label like 'Facebook Murder'.

"Victims knew their killers in most cases, and the crimes ...

Stanching the free flow of blood from an injury remains a holy grail of clinical medicine. Controlling blood flow is a primary concern and first line of defense for patients and medical staff in many situations, from traumatic injury to illness to surgery. If control is not established within the first few minutes of a hemorrhage, further treatment and healing are impossible.

At UC Santa Barbara, researchers in the Department of Chemical Engineering and at Center for Bioengineering (CBE) have turned to the human body's own mechanisms for inspiration in dealing with the ...