(Press-News.org) LAWRENCE -- Like hedonistic rock stars that live by the "better to burn out than to fade away" credo, certain galaxies flame out in a blaze of glory. Astronomers have struggled to grasp why these young "starburst" galaxies -- ones that are very rapidly forming new stars from cold molecular hydrogen gas up to 100 times faster than our own Milky Way -- would shut down their prodigious star formation to join a category scientists call "red and dead."

Starburst galaxies typically result from the merger or close encounter of two separate galaxies. Previous research had revealed spouts of gas shooting outward from such galaxies at up to 2 million miles per hour. But astronomers lacked direct evidence of what expelled the gas, the fundamental ingredient for crafting new stars.

"To form stars you need dense gas," said Gregory Rudnick, associate professor of physics and astronomy at the University of Kansas. "Most of the gas in the universe is made up of hydrogen and in very dense areas this gas is no longer formed of atoms but rather of molecules of hydrogen. When the gas gets dense enough and isn't too hot, small portions of that gas can collapse to form stars. Without a lot of cool dense gas, around -420 to -280 degrees Fahrenheit, stars can't form."

Now, Rudnick and a team of fellow astronomers have solved the mystery of why compact, young galaxies become galactic ruins. Using NASA's Hubble Space Telescope and Chandra X-ray Observatory, they found that energy from the star formation itself created a shortage of gas within the starburst galaxies they studied, shutting down the potential for further crafting of stars. The group's findings were published recently in the Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society.

"As the stars form, the most massive and hot ones emit enough light that the pressure of this light on the gas can push the gas out of the galaxy," Rudnick said. "When these stars explode, the energy from these explosions can do the rest of the job and push most of the gas clear of the galaxy. We think we are witnessing such an occurrence."

Rudnick and his fellow researchers analyzed 12 merging galaxies as the curtain fell on their star making. The team's observations overturned an earlier idea that supermassive black holes, also known as "active galactic nuclei," or AGN, were responsible for throwing gas from these starburst galaxies.

"One favored possibility for this was that the gas that fuels star formation was forcibly ejected from the galaxy over about tens of million years," Rudnick said. "It was suspected that it had something to do with the presence of a supermassive black hole at the center of the galaxy. Just before gas enters a black hole, it can become extremely hot and literally cause a wind that can drive out the gas from the rest of the galaxy. While a possible cause of the blowout, there had been no direct evidence for this process in driving out the gas in these compact galaxies. Indeed, before our studies no one had ever even observed a compact galaxy exhibiting a strong wind and blowing out its gas."

The findings suggest the same extreme condiitions that turn compact galaxies into prolific star-making machines also bring on the eventual demise of their star production. In other words, supermassive black holes, or AGN, aren't to blame.

"There is so much star formation that it's possible the energy from the star formation itself is able to stop the star formation," said the KU researcher. "We originally thought these galaxies might have an accreting supermassive black hole that was causing the breakneck winds. This is because the speeds were so high and we had never seen star formation doing this effective of a job before at pushing a strong wind. This work surprisingly shows that supermassive black holes probably aren't important in causing these outflows. This is important, as many studies of galaxy evolution have shown that these black holes may play a key role in regulating star formation in galaxies.

"What we've shown is these very vigorously star-forming and extremely compact galaxies don't require a big black hole but can do the job via their star formation alone," Rudnick said. "Indeed, the star formation may be occurring at the fastest rate possible before shutting itself off. This is a galaxy that is pushing itself towards a shutdown. This will be an important element to include in future revisions of galaxy evolution models."

INFORMATION:

The Smithsonian Astrophysical Observatory, NASA, the Space Telescope Science Institute and the Alexander von Humboldt Foundation supported this work.

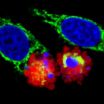

INDIANAPOLIS -- Researchers have identified two proteins that appear crucial to the development -- and patient relapse -- of acute myeloid leukemia. They have also shown they can block the development of leukemia by targeting those proteins.

The studies, in animal models, could lead to new effective treatments for leukemias that are resistant to chemotherapy, said Reuben Kapur, Ph.D., Freida and Albrecht Kipp Professor of Pediatrics at the Indiana University School of Medicine.

The research was reported today in the journal Cell Reports.

"The issue in the field for ...

Plants all over the world are more sensitive to drought than many experts realized, according to a new study by scientists at UCLA and China's Xishuangbanna Tropical Botanical Garden. The research will improve predictions of which plant species will survive the increasingly intense droughts associated with global climate change.

The research is reported online by Ecology Letters, the most prestigious journal in the field of ecology, and will be published in an upcoming print edition.

Predicting how plants will respond to climate change is crucial for their conservation. ...

MOUNT VERNON, Wash. -- A new study by researchers at Washington State University shows that mechanical harvesting of cider apples can provide labor and cost savings without affecting fruit, juice, or cider quality.

The study, published in the journal HortTechnology in October, is one of several studies focused on cider apple production in Washington State. It was conducted in response to growing demand for hard cider apples in the state and the nation.

Quenching a thirst for cider

Hard cider consumption is trending steeply upward in the region surrounding the food-conscious ...

As our society ages, a University of Montreal study suggests the health system should be focussing on comorbidity and specific types of disabilities that are associated with higher health care costs for seniors, especially cognitive disabilities. Comorbidity is defined as the presence of multiple disabilities. Michaël Boissonneault and Jacques Légaré of the university's Department of Demography came to this conclusion after assessing how individual factors are associated with variation in the public costs of healthcare by studying disabled Quebecers over ...

The scientists showed that the Parkin protein functions to repair or destroy damaged nerve cells, depending on the degree to which they are damaged

People living with Parkinson's disease often have a mutated form of the Parkin gene, which may explain why damaged, dysfunctional nerve cells accumulate

Dublin, Ireland, November 13th, 2014 - Scientists at Trinity College Dublin have made an important breakthrough in our understanding of Parkin - a protein that regulates the repair and replacement of nerve cells within the brain. This breakthrough generates a new perspective ...

There are no approved treatments or preventatives against Ebola virus disease, but investigators have now designed peptides that mimic the virus' N-trimer, a highly conserved region of a protein that's used to gain entry inside cells.

The team showed that the peptides can be used as targets to help researchers develop drugs that might block Ebola virus from entering into cells.

"In contrast to the most promising current approaches for Ebola treatment or prevention, which are species-specific, our 'universal' target will enable the selection of broad-spectrum inhibitors ...

In a study of middle-aged men who were overweight, researchers found that if a man's parents were older at the time of his birth, he was more likely to have lower blood pressure, more favorable cholesterol levels, and improved glucose metabolism. It's unknown whether the beneficial effect was due to having an older mother, an older father, or both.

Additional studies are necessary to help shed light on the effects of parental age at childbirth on the metabolism of men and women. "In particular, more research is required to understand whether these effects are due to ...

In a study that looked at what factors might affect whether or not a patient receives intensive medical procedures in the last 6 months of life, investigators found that older age, Alzheimer's disease, cancer, living in a nursing home, and having an advance directive were associated with a lower likelihood of undergoing an intensive procedure. In contrast, living in a region with higher hospital care intensity and black race each doubled a patient's likelihood of undergoing an intensive procedure.

"It's pretty striking the extent to which nonclinical factors--such as ...

Preeclampsia, a late-pregnancy disorder that is characterized by high blood pressure and organ damage, may be caused by problems related to meeting the oxygen demands of the growing fetus, experts say in a new Anaesthesia paper.

Left untreated, preeclampsia can lead to serious--even fatal--complications for a pregnant woman and her baby. The new theory challenges the current view that pre-eclampsia is caused by a problem with the placenta. "When the fetus is not getting enough oxygen and nutrients for its growth--due to conditions in the mother, conditions in the placenta ...

Investigators recently set out to consider whether homicides involving social networking sites were unique and worthy of labels such as 'Facebook Murder', and to explore the ways in which perpetrators had used such sites in the homicides they had committed.

The cases they identified were not collectively unique or unusual when compared with general trends and characteristics--certainly not to a degree that would necessitate the introduction of a new category of homicide or a broad label like 'Facebook Murder'.

"Victims knew their killers in most cases, and the crimes ...