(Press-News.org) TORONTO, ON (13 November 2014) Astronomers from the University of Toronto and the University of Arizona have provided the first direct evidence that an intergalactic "wind" is stripping galaxies of star-forming gas as they fall into clusters of galaxies. The observations help explain why galaxies found in clusters are known to have relatively little gas and less star formation when compared to non-cluster or "field" galaxies.

Astronomers have theorized that as a field galaxy falls into a cluster of galaxies, it encounters the cloud of hot gas at the centre of the cluster. As the galaxy moves through this intra-cluster medium at thousands of kilometres per second, the cloud acts like a wind, blowing away the gas within the galaxy without disturbing its stars. The process is known as ram-pressure stripping.

Previously, astronomers had seen the very tenuous atomic hydrogen gas surrounding a galaxy get stripped. But it was believed that the denser molecular hydrogen clouds where stars form would be more resistant to the wind. "However, we found that the molecular hydrogen gas is also blown from the in-falling galaxy," says Suresh Sivanandam of the Dunlap Institute at the University of Toronto, "much like smoke blown from a candle being carried into a room."

Previous observations showed indirect evidence of ram-pressure stripping of star-forming gas. Astronomers have observed young stars trailing from a galaxy; the stars would have formed from gas newly-stripped from the galaxy. A few galaxies also have tails of very tenuous gas. But the latest observations show the stripped, molecular hydrogen itself, which can be seen as a wake trailing from the galaxy in the direction opposite to its motion.

"For more than 40 years we have been trying to understand why galaxies in dense clusters have so few young stars compared with ones like our Milky Way Galaxy, but now we see the quenching of star formation in action," says George Rieke of the University of Arizona. "Cutting off the gas that forms stars is a key step in the evolution of galaxies from the early Universe to the present."

The results, published in the Astrophysical Journal on Nov. 10, are from observations of four galaxies. Sivanandam, Rieke and colleague Marcia Rieke (also from the University of Arizona) had already established that one of the four galaxies had been stripped of its star-forming gas by this wind. But by observing four galaxies, they have now shown that this effect is common.

The team made their analysis using optical, infrared and hydrogen-emission data from the Spitzer and Hubble space telescopes, as well as archival ground-based data. The team used an infrared spectrograph on the Spitzer because direct observation of the molecular hydrogen required observations in the mid-infrared part of the spectrum--something that's almost impossible to do from the ground.

"Seeing this stripped molecular gas is like seeing a theory on display in the sky," says Marcia Rieke. "Astronomers have assumed that something stopped the star formation in these galaxies, but it is very satisfying to see the actual cause."

INFORMATION:

See the paper:

http://iopscience.iop.org/0004-637X/796/2/89/

Image information:

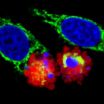

A composite image shows the galaxy NGC 4522 in the Virgo Cluster, the nearest large cluster of galaxies to our own local group of galaxies, and the "wake" of gas and dust being blown from the galaxy. The galaxy appears blue in the Hubble Space Telescope image in visible light. The superimposed red image is from Spitzer data and shows emissions from dust that traces molecular hydrogen. In the image, the galaxy is moving down and into the plane of the photo.

Image credit: Suresh Sivanandam; Dunlap Institute for Astronomy & Astrophysics

Contact information

Dr. Suresh Sivanandam

Dunlap Institute for Astronomy & Astrophysics

University of Toronto

p: 416-978-2183

e: sivanandam@dunlap.utoronto.ca

Professor George Rieke

Steward Observatory

University of Arizona

e: grieke@as.arizona.edu

Professor Marcia Rieke

Steward Observatory

University of Arizona

e: mrieke@as.arizona.edu

Chris Sasaki

Communications Coordinator

Dunlap Institute for Astronomy & Astrophysics

University of Toronto

p: 416-978-6613

e: csasaki@dunlap.utoronto.ca

Daniel Stolte

Office of University Relations, Communications

University of Arizona

p: 520-626-4402

e: stolte@email.arizona.edu

The Dunlap Institute for Astronomy & Astrophysics, University of Toronto, continues the legacy of the David Dunlap Observatory by developing innovative astronomical instrumentation, including for the largest, most advanced telescopes in the world; by training the next generation of astronomers; and by fostering public engagement in science. The research of its faculty and postdoctoral fellows includes the discovery of exoplanets, the formation of stars, galactic nuclei, the evolution and nature of galaxies, the early Universe and the Cosmic Microwave Background, and the Search for Extra-terrestrial Intelligence (SETI). Together, the Dunlap Institute, the University of Toronto's Department of Astronomy & Astrophysics, and the Canadian Institute for Theoretical Astrophysics comprise the leading centre for astronomical research in Canada at the country's leading research university.

For more information: http://dunlap.utoronto.ca

Some plants form into new species with a little help from their friends, according to Cornell University research published Oct. 27 in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences.

The study finds that when plants develop mutually beneficial relationships with animals, mainly insects, those plant families become more diverse by evolving into more species over time.

The researchers conducted a global analysis of all vascular plant families, more than 100 of which have evolved sugary nectar-secreting glands that attract and feed protective animals, such as ants. ...

Who would have thought a Sesame Street video starring the Cookie Monster, of all characters, could teach preschoolers self-control?

But that's exactly what Deborah Linebarger, an associate professor in Teacher and Learning at the University of Iowa, found when she studied a group of preschoolers who repeatedly watched videos of Cookie Monster practicing ways to control his desire to eat a bowl of chocolate chip cookies.

"Me want it," Cookie Monster sings in one video, "but me wait."

In fact, preschoolers who viewed the Cookie Monster video were able to wait four ...

In a potential breakthrough against ovarian cancer, University of Guelph researchers have discovered how to both shrink tumours and improve drug delivery, allowing for lower doses of chemotherapy and reducing side effects.

Their research appears today in the FASEB Journal, one of the world's top biology publications.

"We hope that this study will lead to novel treatment approaches for women diagnosed with late-stage ovarian cancer," said Jim Petrik, a Guelph biomedical sciences professor. He worked on the study with Guelph graduate student Samantha Russell and cancer ...

LAWRENCE -- Like hedonistic rock stars that live by the "better to burn out than to fade away" credo, certain galaxies flame out in a blaze of glory. Astronomers have struggled to grasp why these young "starburst" galaxies -- ones that are very rapidly forming new stars from cold molecular hydrogen gas up to 100 times faster than our own Milky Way -- would shut down their prodigious star formation to join a category scientists call "red and dead."

Starburst galaxies typically result from the merger or close encounter of two separate galaxies. Previous research had revealed ...

INDIANAPOLIS -- Researchers have identified two proteins that appear crucial to the development -- and patient relapse -- of acute myeloid leukemia. They have also shown they can block the development of leukemia by targeting those proteins.

The studies, in animal models, could lead to new effective treatments for leukemias that are resistant to chemotherapy, said Reuben Kapur, Ph.D., Freida and Albrecht Kipp Professor of Pediatrics at the Indiana University School of Medicine.

The research was reported today in the journal Cell Reports.

"The issue in the field for ...

Plants all over the world are more sensitive to drought than many experts realized, according to a new study by scientists at UCLA and China's Xishuangbanna Tropical Botanical Garden. The research will improve predictions of which plant species will survive the increasingly intense droughts associated with global climate change.

The research is reported online by Ecology Letters, the most prestigious journal in the field of ecology, and will be published in an upcoming print edition.

Predicting how plants will respond to climate change is crucial for their conservation. ...

MOUNT VERNON, Wash. -- A new study by researchers at Washington State University shows that mechanical harvesting of cider apples can provide labor and cost savings without affecting fruit, juice, or cider quality.

The study, published in the journal HortTechnology in October, is one of several studies focused on cider apple production in Washington State. It was conducted in response to growing demand for hard cider apples in the state and the nation.

Quenching a thirst for cider

Hard cider consumption is trending steeply upward in the region surrounding the food-conscious ...

As our society ages, a University of Montreal study suggests the health system should be focussing on comorbidity and specific types of disabilities that are associated with higher health care costs for seniors, especially cognitive disabilities. Comorbidity is defined as the presence of multiple disabilities. Michaël Boissonneault and Jacques Légaré of the university's Department of Demography came to this conclusion after assessing how individual factors are associated with variation in the public costs of healthcare by studying disabled Quebecers over ...

The scientists showed that the Parkin protein functions to repair or destroy damaged nerve cells, depending on the degree to which they are damaged

People living with Parkinson's disease often have a mutated form of the Parkin gene, which may explain why damaged, dysfunctional nerve cells accumulate

Dublin, Ireland, November 13th, 2014 - Scientists at Trinity College Dublin have made an important breakthrough in our understanding of Parkin - a protein that regulates the repair and replacement of nerve cells within the brain. This breakthrough generates a new perspective ...

There are no approved treatments or preventatives against Ebola virus disease, but investigators have now designed peptides that mimic the virus' N-trimer, a highly conserved region of a protein that's used to gain entry inside cells.

The team showed that the peptides can be used as targets to help researchers develop drugs that might block Ebola virus from entering into cells.

"In contrast to the most promising current approaches for Ebola treatment or prevention, which are species-specific, our 'universal' target will enable the selection of broad-spectrum inhibitors ...