Unveiling the effects of an important class of diabetes drugs

New research explains how thiazolidinediones work to improve glucose metabolism, suggests potential role for MEK inhibitors in diabetes

2014-11-17

(Press-News.org) BOSTON - A research team led by Brigham and Women's Hospital (BWH) and Dana-Farber Cancer Institute (DFCI) has uncovered surprising new findings that underscore the role of an important signaling pathway, already known to be critical in cancer, in the development of type 2 diabetes. Their results, published in the November 17, 2014 advance online issue of the journal Nature, shed additional light on how a longstanding class of diabetes drugs, known as thiazolidinediones (TZDs), work to improve glucose metabolism and suggest that inhibitors of the signaling pathway -- known as the MEK/ERK pathway -- may also hold promise in the treatment of type 2 diabetes.

"It's been recognized that thiazolidinediones have tremendous benefits in the treatment of type 2 diabetes, but they also have significant risks," said Alexander S. Banks, PhD, lead author and a researcher in the Division of Endocrinology, Diabetes and Hypertension at BWH. "The question is, can we minimize these adverse effects by modifying the drugs slightly or by approaching the pathway from a different direction?"

This hypothesis led Banks and DFCI's Bruce Spiegelman, PhD, a researcher in the department of Cancer Biology at Dana-Farber, to focus on a critical molecular player known as CDK5. A type of enzyme known as a kinase, CDK modifies a key site on the molecule targeted by TZDs (known as PPARγ). To further understand CDK5's role, Banks and his colleagues created a special strain of mice lacking CDK5 in adipose tissues --where PPARγ is most highly active and TZDs are thought to act.

Instead of confirming their initial suspicions about CDK5, the team's results pointed them in a very different direction: their findings suggested that another key kinase was involved. In collaboration with researchers at Harvard Medical School, Banks, Spiegelman and their colleagues conducted a wide, unbiased search to determine its identity. That search ultimately led them to the kinase known as ERK.

After a detailed biochemical study of ERK function, the team set out to test its role in glucose metabolism, and found that MEK inhibitors, which block ERK function, significantly improve insulin resistance in mouse models of diabetes.

"A new class of drugs, aimed primarily at cancer, has been developed that inhibits ERK's action. These drugs, known as MEK inhibitors, help to extend the lives of patients with advanced cases of melanoma," said Banks. "One of the most exciting aspects of this paper is the concept that you could inhibit the abnormal activation of ERK seen in diabetes using these MEK inhibitors designed for treating cancer, but at lower, safer doses."

"All attempts to develop new therapeutics will carry risks, but the opportunities here certainly seem worth exploring in the clinic," said Spiegelman.

While much more work must be done to determine if MEK inhibitors will be a safe and effective treatment for type 2 diabetes, the Nature study offers an important window on the molecular underpinnings of TZD action. In addition, it suggests that MEK/ERK inhibition may offer a viable route toward minimizing the drugs' undesired effects.

INFORMATION:

This work was supported by the National Institutes of Health (grants DK31405 and DK93638), the Harvard University Milton Fund, and the Harvard Digestive Disease Center, Core D.

Brigham and Women's Hospital (BWH) is a 793-bed nonprofit teaching affiliate of Harvard Medical School and a founding member of Partners HealthCare. BWH has more than 3.5 million annual patient visits, is the largest birthing center in Massachusetts and employs nearly 15,000 people. The Brigham's medical preeminence dates back to 1832, and today that rich history in clinical care is coupled with its national leadership in patient care, quality improvement and patient safety initiatives, and its dedication to research, innovation, community engagement and educating and training the next generation of health care professionals. Through investigation and discovery conducted at its Brigham Research Institute (BRI), BWH is an international leader in basic, clinical and translational research on human diseases, more than 1,000 physician-investigators and renowned biomedical scientists and faculty supported by nearly $650 million in funding. For the last 25 years, BWH ranked second in research funding from the National Institutes of Health (NIH) among independent hospitals. BWH continually pushes the boundaries of medicine, including building on its legacy in transplantation by performing a partial face transplant in 2009 and the nation's first full face transplant in 2011. BWH is also home to major landmark epidemiologic population studies, including the Nurses' and Physicians' Health Studies and the Women's Health Initiative. For more information, resources and to follow us on social media, please visit BWH's online newsroom.

Dana-Farber Cancer Institute, a principal teaching affiliate of Harvard Medical School, is world renowned for its leadership in adult and pediatric cancer treatment and research. Designated as a comprehensive cancer center by the National Cancer Institute (NCI), it is one of the largest recipients among independent hospitals of NCI and National Institutes of Health grant funding. For more information, go to http://www.dana-farber.org.

ELSE PRESS RELEASES FROM THIS DATE:

2014-11-17

PROVIDENCE, R.I. [Brown University] -- Ample evidence of ancient rivers, streams, and lakes make it clear that Mars was at some point warm enough for liquid water to flow on its surface. While that may conjure up images of a tropical Martian paradise, new research published today in Nature Geoscience throws a bit of cold water on that notion.

The study, by scientists from Brown University and Israel's Weizmann Institute of Science, suggests that warmth and water flow on ancient Mars were probably episodic, related to brief periods of volcanic activity that spewed tons ...

2014-11-17

A team of New York University and University of Barcelona physicists has developed a method to control the movements occurring within magnetic materials, which are used to store and carry information. The breakthrough could simultaneously bolster information processing while reducing the energy necessary to do so.

Their method, reported in the most recent issue of the journal Nature Nanotechnology, manipulates "spin waves," which are waves that move in magnetic materials. Physically, these spin waves are much like water waves--like those that propagate on the surface ...

2014-11-17

In what is likely to be a major step forward in the study of influenza, cystic fibrosis and other human diseases, an international research effort has a draft sequence of the ferret genome. The sequence was then used to analyze how the flu and cystic fibrosis affect respiratory tissues at the cellular level.

The National Institute of Allergy and infectious Diseases, of the National Institutes of Health, funded the project that was coordinated by Michael Katze and Xinxia Peng at the University of Washington in Seattle and Federica Di Palma and Jessica Alfoldi at the Broad ...

2014-11-17

LA JOLLA, CA - November 17, 2014 - For decades, scientists thought drug addiction was the result of two separate systems in the brain--the reward system, which was activated when a person used a drug, and the stress system, which kicked in during withdrawal.

Now scientists at The Scripps Research Institute (TSRI) have found that these two systems are actually linked. Their findings, published November 17 in the journal Nature Neuroscience, show that in the core of the brain's reward system are specific neurons that are active both with use of and withdrawal from nicotine. ...

2014-11-17

Joseph B. Muhlestein, M.D., of the Intermountain Medical Center Heart Institute, Murray, Utah, and colleagues examined whether screening patients with diabetes deemed to be at high cardiac risk with coronary computed tomographic angiography (CCTA) would result in a significant longterm reduction in death, heart attack, or hospitalization for unstable angina. The study appears in JAMA and is being released to coincide with its presentation at the American Heart Association's Scientific Sessions 2014.

Diabetes mellitus is the most important coronary artery disease ...

2014-11-17

Yasuo Ikeda, M.D., of Waseda University, Tokyo, Japan, and colleagues examined whether once-daily, low-dose aspirin would reduce the total number of cardiovascular (CV) events (death from CV causes, nonfatal heart attack or stroke) compared with no aspirin in Japanese patients 60 years or older with hypertension, diabetes, or poor cholesterol or triglyceride levels. The study appears in JAMA and is being released to coincide with its presentation at the American Heart Association's Scientific Sessions 2014.

The World Health Organization estimates that annual global mortality ...

2014-11-17

DALLAS - November 17, 2014 - Using next generation gene sequencing techniques, cancer researchers at UT Southwestern Medical Center have identified more than 3,000 new mutations involved in certain kidney cancers, findings that help explain the diversity of cancer behaviors.

"These studies, which were performed in collaboration with Genentech Inc., identify novel therapeutic targets and suggest that predisposition to kidney cancer across species may be explained, at least in part, by the location of tumor suppressor genes with respect to one another in the genome," said ...

2014-11-17

Washington, D.C.--Silicon is the second most-abundant element in the earth's crust. When purified, it takes on a diamond structure, which is essential to modern electronic devices--carbon is to biology as silicon is to technology. A team of Carnegie scientists led by Timothy Strobel has synthesized an entirely new form of silicon, one that promises even greater future applications. Their work is published in Nature Materials.

Although silicon is incredibly common in today's technology, its so-called indirect band gap semiconducting properties prevent it from being ...

2014-11-17

HOUSTON -- (Nov. 17, 2014) - A compound called calcein may act to inhibit topoisomerase IIβ-binding protein 1 (TopBP1), which enhances the growth of tumors, said researchers from Baylor College of Medicine in a report that appears online in the journal Nature Communications.

"The progression of many solid tumors is driven by de-regulation of multiple common pathways," said Dr. Weei-Chin Lin, associate professor of medicine- hematology & oncology, and a member of the NCI-designated Dan L. Duncan Cancer Center at Baylor. Among those are the retinoblastoma (Rb), PI(3)K/Akt ...

2014-11-17

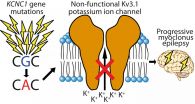

A study led by researchers at University of Helsinki, Finland and Universities of Melbourne and South Australia has identified a new gene for a progressive form of epilepsy. The findings of this international collaborative effort have been published today, 17 November 2014, in Nature Genetics.

Progressive myoclonus epilepsies (PME) are rare, inherited, and usually childhood-onset neurodegenerative diseases whose core symptoms are epileptic seizures and debilitating involuntary muscle twitching (myoclonus). The goal of the international collaborative study was to identify ...

LAST 30 PRESS RELEASES:

[Press-News.org] Unveiling the effects of an important class of diabetes drugs

New research explains how thiazolidinediones work to improve glucose metabolism, suggests potential role for MEK inhibitors in diabetes