(Press-News.org) WASHINGTON, D.C. - An antidepressant commonly prescribed for women with postpartum depression may restore connections between cells in brain regions that are negatively affected by chronic stress during pregnancy, new research suggests.

Ohio State University scientists found that rats that had been chronically stressed during pregnancy showed depressive-like behaviors after giving birth, and structures in certain areas of their brains were less complex than in unstressed rats. After receiving the drug for three weeks, these rats had no depressive symptoms and neurons in their brains showed normal structural complexity.

The antidepressant is Citalopram, an agent from the class of drugs known as selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors that is sold under the brand name Celexa.

"We saw that Citalopram was effective in improving mood in stressed mothers and completely reversed the stress effects in areas of the brain that our lab has shown are altered by stress during pregnancy," said lead author Achikam Haim, a student in the Neuroscience Graduate Program at Ohio State.

Haim presented the research Wednesday (Nov. 19) at Neuroscience 2014, the annual meeting of the Society for Neuroscience.

While clinical signs of postpartum depression are clear, researchers are still figuring out what happens in the brain when mothers suffer this devastating problem.

Benedetta Leuner, assistant professor of psychology and neuroscience at Ohio State and senior author of the work, has designed a rat model of postpartum depression to help explain brain changes. Her lab induces depressive-like symptoms in rats by subjecting the animals to chronic stress during pregnancy - chronic stress in pregnancy is a known predictor of postpartum depression in humans.

As parents, the rats show symptoms that resemble those in humans with postpartum depression - they are unable to experience pleasure, indicating a condition called anhedonia, and float more than unstressed rats during a water test; animals that float rather than swim are showing depressive-like symptoms. Along with mood changes, depressed mothers - humans and animals - show deficits in caregiving behaviors.

The current work aims to identify brain changes that may underlie these symptoms and focuses on a region called the nucleus accumbens, which regulates feelings of reward and motivation.

"We have a suspicion that stress during pregnancy is somehow altering the reward system in the brain, producing anhedonia and making these depressed mothers less rewarded by their offspring and less motivated to care for them," Leuner said. "It's possible that the effects of stress on the brain circuit regulating reward can lead to these symptoms."

The scientists found that the reward center in the brains of stressed rats had fewer dendritic spines - hair-like growths on brain cells that are used to exchange information with other neurons - than did brains of unstressed rats. This is a sign of reduced plasticity, which refers to the brain's flexibility or ability to adapt.

This finding mirrors research in humans that revealed that the reward center in mothers with postpartum depression failed to activate in response to audio of their infants crying. "The structural data from our work in rats can at least partially explain that, because neurons with fewer spines, and therefore less input, arguably have lower activation levels," Haim said.

The researchers implanted mini-pumps under the skin of mother rats with depressive-like symptoms to administer daily doses of Citalopram for three weeks. After treatment, in addition to the brain changes, the rats responded normally during a water test by swimming vigorously.

The typical three-week time frame for antidepressants to become effective suggests these medications are not sufficient, however, to address a potentially more urgent component of postpartum depression: poor maternal care. A depressed mother's neglect can have long-term effects on children that include slowed cognitive and social development and increased susceptibility to depression in adulthood.

"We're now looking at other neurochemical systems to target," Leuner said. "Fixing that impaired maternal functioning is really what's critical in moving forward and developing better treatment options."

INFORMATION:

This work is supported by a grant from the National Institute of Mental Health.

Additional co-authors on the presentation are technician Christopher Albin-Brooks and undergraduate students Morgan Sherer and Emily Mills, all of Ohio State's Department of Psychology.

Contacts: Benedetta Leuner, (614) 292-5218; Leuner.1@osu.edu or Achikam Haim, haim.1@osu.edu

Written by Emily Caldwell, (614) 292-8310; Caldwell.151@osu.edu

(To reach Leuner or Haim during Neuroscience 2014, send them an email or call Emily Caldwell at 614-893-4261.)

Scientific Presentation: 773.04, "Postpartum depressive-like behavior is accompanied by impaired maternal motivation and altered structural plasticity within the reward system," 1:45-2 p.m. Nov. 19, Washington Convention Center Room 140A

New York City residents' movement around the city was perturbed, but resumed less than 24-hours after Hurricane Sandy, according to a study published November 19, 2014 in the open-access journal PLOS ONE by Qi Wang and John Taylor from Virginia Tech.

Tropical cyclones, including hurricanes and typhoons, are severe natural disasters that can cause tremendous loss of human life and suffering. Our knowledge of peoples' movements during natural disasters is so far limited due to a lack of data. The authors of this article studied human mobility using movement data from individuals ...

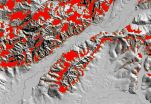

CORVALLIS, Ore. - Engineers have created a new way to use lidar technology to identify and classify landslides on a landscape scale, which may revolutionize the understanding of landslides in the U.S. and reveal them to be far more common and hazardous than often understood.

The new, non-subjective technology, created by researchers at Oregon State University and George Mason University, can analyze and classify the landslide risk in an area of 50 or more square miles in about 30 minutes - a task that previously might have taken an expert several weeks to months. It can ...

TALLAHASSEE, Fla. -- A new study by a Florida State University biologist shows that bleaching events brought on by rising sea temperatures are having a detrimental long-term impact on coral.

Professor Don Levitan, chair of the Department of Biological Science, writes in the latest issue of Marine Ecology Progress Series that bleaching -- a process where high water temperatures or UV light stresses the coral to the point where it loses its symbiotic algal partner that provides the coral with color -- is also affecting the long-term fertility of the coral.

"Even corals ...

New research has found that one of the world's most prolific bacteria manages to afflict humans, animals and even plants by way of a mechanism not before seen in any infectious microorganism -- a sense of touch. This unique ability helps make the bacteria Pseudomonas aeruginosa ubiquitous, but it also might leave these antibiotic-resistant organisms vulnerable to a new form of treatment.

Pseudomonas is the first pathogen found to initiate infection after merely attaching to the surface of a host, Princeton University and Dartmouth College researchers report in the journal ...

A social sensing game created at Illinois allows researchers to study natural interactions between children, collect large amounts of data about those interactions and test theories about youth aggression and victimization.

The game's behavior analyses effectively identify classroom bullies, even revealing peer aggression that goes undetected by traditional research methods, the researchers say.

The game's developers say it is an improvement over traditional research methods, such as questionnaires, which do not assess interactions between youth in real time.

"What ...

When the mouse and human genomes were catalogued more than 10 years ago, an international team of researchers set out to understand and compare the "mission control centers" found throughout the large stretches of DNA flanking the genes. Their long-awaited report, published Nov. 19 in the journal Nature suggests why studies in mice cannot always be reproduced in humans. Importantly, the scientists say, their work also sheds light on the function of DNA's regulatory regions, which are often to blame for common chronic human diseases.

"Most of the differences between mice ...

Microbiologists at NYU Langone Medical Center say they have what may be the first strong evidence that the natural presence of viruses in the gut -- or what they call the 'virome' -- plays a health-maintenance and infection-fighting role similar to that of the intestinal bacteria that dwell there and make up the "microbiome."

In a series of experiments in mice that took two years to complete, the NYU Langone team found that infection with the common murine norovirus, or MNV, helped mice repair intestinal tissue damaged by inflammation and helped restore the gut's immune ...

For years, scientists have considered the laboratory mouse one of the best models for researching disease in humans because of the genetic similarity between the two mammals. Now, researchers at the Stanford University School of Medicine have found that the basic principles of how genes are controlled are similar in the two species, validating the mouse's utility in clinical research.

However, there are important differences in the details of gene regulation that distinguish us as a species.

"At the end of the day, a lot of the genes are identical between a mouse and ...

For more than a century, the laboratory mouse (Mus musculus) has stood in for humans in experiments ranging from deciphering disease and brain function to explaining social behaviors and the nature of obesity. The small rodent has proven to be an indispensable biological tool, the basis for decades of profound scientific discovery and medical progress.

But in new findings published online Nov. 19 in the journal Nature, researchers at the University of California, San Diego School of Medicine and Ludwig Cancer Research, with colleagues across the country and world, have ...

TALLAHASSEE, Fla. -- A new line of research from a team at Florida State University is pushing the limits on what the world knows about how human genetic material is replicated and what that means for people with diseases where the replication process is disrupted, such as cancer.

The team, lead by Department of Biological Sciences Professor David Gilbert and post-doctoral researcher Ben Pope, has taken an in-depth look at how DNA and the associated genetic material replicate and organize within a cell's nucleus. Their work could be especially crucial for doctors and ...