The unbelievable underworld and its impact on us all

2014-11-26

(Press-News.org) A new study has pulled together research into the most diverse place on earth to demonstrate how the organisms below-ground could hold the key to understanding how the worlds ecosystems function and how they are responding to climate change.

Published in Nature, the paper by Professor Richard Bardgett from The University of Manchester and Professor Wim van der Putten of the Netherlands Institute of Ecology, brings together new knowledge on this previously neglected area. The paper not only highlights the sheer diversity of life that lives below-ground, but also how rapid responses of soil organisms to climate change could have far reaching impacts on future ecosystems. The paper also explores how the below-ground world can be utilised for sustainable land management.

Professor Bardgett explains: "The soil beneath our feet arguably represents the most diverse place on Earth. Soil communities are extremely complex with literally millions of species and billions of individual organisms within a single grassland or forest, ranging from microscopic bacteria and fungi through to larger organisms such as earthworms, ants and moles. Despite this plethora of life the underground world had been largely neglected by research, it certainly used to be a case of out of sight out of mind, although over the last decade we have seen a significant increase in work in this area."

The increase in research on below-ground organisms has helped to explain how they interact with each other and crucially how they influence the above-ground flora and fauna.

Professor van der Putten says: "For example, an increasing number of studies show that above-ground pest control is influenced by organisms in the soil. This supports the view that a healthy crop requires healthy soil."

Professor Bardgett says there have been some other fascinating results: "Recent soil biodiversity research has revealed that below-ground communities not only play a major role in shaping plant biodiversity and the way that ecosystems function, but it can also determine how they respond to environmental change."

He continues: "One of the key areas for future research will be to integrate what has been learnt about soil diversity into decisions about sustainable land management. There is an urgent need for new approaches to the maintenance and enhancement of soil fertility for food, feed and biomass production, the prevention of human disease and tackling climate change. As we highlight in this paper, a new age of research is needed to meet these scientific challenges and to integrate such understanding into future land management and climate change mitigation strategies."

With the publication of this paper Professor Bardgett is optimistic for the future: "Soil biodiversity research is now entering a new era; awareness is growing among scientists and policy makers of the importance of soil biodiversity for the supply of ecosystem goods and services to human society. New technologies are allowing us to study underground ecosystems in situ and a new generation of tools are available to properly investigate the biology of soil and its ecological and evolutionary role."

INFORMATION:

[Attachments] See images for this press release:

ELSE PRESS RELEASES FROM THIS DATE:

2014-11-26

Scientists from Queen Mary University of London have made a breakthrough in developing a new therapy for advanced bladder cancer - for which there have been no major treatment advances in the past 30 years.

Published today in Nature, the study examined an antibody (MPDL3280A) which blocks a protein (PD-L1) thought to help cancer cells evade immune detection.

In a phase one, multi-centre international clinical trial, 68 patients with advanced bladder cancer (who had failed all other standard treatments such as chemotherapy) received MPDL3280A, a cancer immunotherapy ...

2014-11-26

In the race to find materials of ever increasing thinness, surface area and conductivity to make better performing battery electrodes, a lump of clay might have just taken the lead. Materials scientists from Drexel University's College of Engineering invented the clay, which is both highly conductive and can easily be molded into a variety of shapes and sizes. It represents a turn away from the rather complicated and costly processing--currently used to make materials for lithium-ion batteries and supercapacitors--and toward one that looks a bit like rolling out cookie ...

2014-11-26

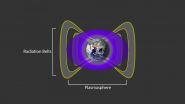

A team led by the University of Colorado Boulder has discovered an invisible shield some 7,200 miles above Earth that blocks so-called "killer electrons," which whip around the planet at near-light speed and have been known to threaten astronauts, fry satellites and degrade space systems during intense solar storms.

The barrier to the particle motion was discovered in the Van Allen radiation belts, two doughnut-shaped rings above Earth that are filled with high-energy electrons and protons, said Distinguished Professor Daniel Baker, director of CU-Boulder's Laboratory ...

2014-11-26

In the near future, physicians may treat some cancer patients with personalized vaccines that spur their immune systems to attack malignant tumors. New research led by scientists at Washington University School of Medicine in St. Louis has brought the approach one step closer to reality.

Like flu vaccines, cancer vaccines in development are designed to alert the immune system to be on the lookout for dangerous invaders. But instead of preparing the immune system for potential pathogen attacks, the vaccines will help key immune cells recognize the unique features of cancer ...

2014-11-26

LOS ANGELES - November 26, 2014 - Work supported by the Stand Up To Cancer (SU2C) - Cancer Research Institute (CRI) - Immunology Translational Research Dream Team, launched in 2012 to focus on how the patient's own immune system can be harnessed to treat some cancers have pioneered an approach to predict why advanced melanoma patients respond to a new life-saving melanoma drug. This new drug, pembrolizumab (Keytruda), was recently approved by the FDA. These findings are reported in Nature online November 26, 2014, ahead of print in the journal.

Over a two-year study, ...

2014-11-26

High above Earth's atmosphere, electrons whiz past at close to the speed of light. Such ultrarelativistic electrons, which make up the outer band of the Van Allen radiation belt, can streak around the planet in a mere five minutes, bombarding anything in their path. Exposure to such high-energy radiation can wreak havoc on satellite electronics, and pose serious health risks to astronauts.

Now researchers at MIT, the University of Colorado, and elsewhere have found there's a hard limit to how close ultrarelativistic electrons can get to the Earth. The team found that ...

2014-11-26

CORVALLIS, Ore. - The use of renewable energy in the United States could take a significant leap forward with improved storage technologies or more efforts to "match" different forms of alternative energy systems that provide an overall more steady flow of electricity, researchers say in a new report.

Historically, a major drawback to the use and cost-effectiveness of alternative energy systems has been that they are too variable - if the wind doesn't blow or the sun doesn't shine, a completely different energy system has to be available to pick up the slack. This lack ...

2014-11-26

Two donuts of seething radiation that surround Earth, called the Van Allen radiation belts, have been found to contain a nearly impenetrable barrier that prevents the fastest, most energetic electrons from reaching Earth.

The Van Allen belts are a collection of charged particles, gathered in place by Earth's magnetic field. They can wax and wane in response to incoming energy from the sun, sometimes swelling up enough to expose satellites in low-Earth orbit to damaging radiation. The discovery of the drain that acts as a barrier within the belts was made using NASA's ...

2014-11-26

PROVIDENCE, R.I. [Brown University] -- A new study led by Brown University reports that older learners retained the mental flexibility needed to learn a visual perception task but were not as good as younger people at filtering out irrelevant information.

The findings undermine the conventional wisdom that the brains of older people lack flexibility, or "plasticity," but highlight a different reason why learning may become more difficult as people age: They learn more than they need to. Researchers call this the "plasticity and stability dilemma." The new study suggests ...

2014-11-26

VIDEO:

When people hear another person talking to them, they respond not only to what is being said -- those consonants and vowels strung together into words and sentences --but also...

Click here for more information.

When people hear another person talking to them, they respond not only to what is being said--those consonants and vowels strung together into words and sentences--but also to other features of that speech--the emotional tone and the speaker's gender, for instance. ...

LAST 30 PRESS RELEASES:

[Press-News.org] The unbelievable underworld and its impact on us all