INFORMATION:

About Columbia University's Mailman School of Public Health

Founded in 1922, Columbia University's Mailman School of Public Health pursues an agenda of research, education, and service to address the critical and complex public health issues affecting New Yorkers, the nation and the world. The Mailman School is the third largest recipient of NIH grants among schools of public health. Its over 450 multi-disciplinary faculty members work in more than 100 countries around the world, addressing such issues as preventing infectious and chronic diseases, environmental health, maternal and child health, health policy, climate change & health, and public health preparedness. It is a leader in public health education with over 1,300 graduate students from more than 40 nations pursuing a variety of master's and doctoral degree programs. The Mailman School is also home to numerous world-renowned research centers including ICAP (formerly the International Center for AIDS Care and Treatment Programs) and the Center for Infection and Immunity. For more information, please visit http://www.mailman.columbia.edu

People conceived during the Dutch famine have altered regulation of growth genes

May have helped these individuals to adjust to conditions

2014-12-03

(Press-News.org) December 3, 2014 -- Individuals conceived in the severe Dutch Famine, also called the Hunger Winter, may have adjusted to this horrendous period of World War II by making adaptations to how active their DNA is. Genes involved in growth and development were differentially regulated, according to researchers at the Leiden University Medical Center, Harvard University, and Columbia University's Mailman School of Public Health. Findings are published in the journal Nature Communications.

During the winter of 1944-1945 the Western part of The Netherlands was struck by a severe 6-month famine. During this Hunger Winter the available rations provided as low as a quarter of the daily energy requirements. Children conceived -- but not born -- during the famine were delivered with a normal birth weight. Extensive research on the DNA of these Hunger Winter children shows that the regulatory systems of their growth genes were altered, which may also explain why they appear to be at higher risk for metabolic disease in later life.

Decades later growth genes seemed different

"The different setting of the growth genes may have helped the Hunger Winter children to withstand the Famine conditions as compared with their unexposed siblings, but these changes may likewise be unfavorable for their metabolism as adults," said Leiden University principal investigator Dr. Bas Heijmans. For example, the altered settings were associated with LDL cholesterol at age 60, according to the authors.

The research team in Leiden compared the DNA of the Hunger Winter children, now aged 60, at 1.2 million CpG methylation sites comparing them with same-sex siblings not exposed to famine. They were able to see how the genes were differentially regulated in the Hunger Winter children, as compared with their siblings with a similar genetic and familial background. Groups of genes involved in growth and development showed a different gene activity setting. The Hunger Winter children were all approximately 60 years of age when they gave blood for DNA research. It was at this point in time that their growth genes seem altered for life.

"The potential for a gene to become active is mainly determined in the crucial weeks after fertilization. This master regulatory system that determines which genes are on and which are off is called epigenetics and can be compared to a sound technician making adjustments during a recording to get that perfect sound. Environmental factors during development can make a lasting imprint on this system," noted Dr. Heijmans.

The authors point out that a wealth of past epidemiological studies suggests that early development is important for later health. "Thanks to the willingness of the Hunger Winter children and their families to contribute to our studies, we can pin- point which phases of development are especially sensitive to the environment. We are currently extending our inquiries not only to those conceived during the famine, but also to those exposed during other gestation periods. A lot of important things are happening in the womb about which we know quite little in humans", says co-author Dr. Elmar W. Tobi.

"These findings are exciting and provide tremendous opportunities for epidemiologists," said L.H. Lumey, MD, associate professor of Epidemiology at Columbia University's Mailman School of Public Health and senior author who collected the analyzed blood samples. "Looking at the human genome we see systematic changes in gene regulation during early human development in response to the environment. The epigenetic revolution has given us the tools to investigate these changes and look at the impact for later life."

ELSE PRESS RELEASES FROM THIS DATE:

UNC researchers pinpoint chemo effect on brain cells, potential link to autism

2014-12-03

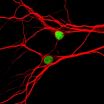

CHAPEL HILL, NC - UNC School of Medicine researchers have found for the first time a biochemical mechanism that could be a cause of "chemo brain" - the neurological side effects such as memory loss, confusion, difficulty thinking, and trouble concentrating that many cancer patients experience while on chemotherapy to treat tumors in other parts of the body.

The research, published in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, shows how the common chemotherapy drug topotecan can drastically suppress the expression of Topoisomerase-1, a gene that triggers the ...

Green meets nano

2014-12-03

Coffee, apple juice, and vitamin C: things that people ingest every day are experimental material for chemist Eva-Maria Felix. The doctoral student in the research group of Professor Wolfgang Ensinger in the Department of Material Analysis is working on making nanotubes of gold. She precipitates the precious metal from an aqueous solution onto a pretreated film with many tiny channels. The metal on the walls of the channels adopts the shape of nanotubes; the film is then dissolved. The technique itself is not new, but Felix has modified it: "The chemicals that are usually ...

REPORT: More Hispanics Earning Bachelor's Degrees in Physical Sciences and Engineering

2014-12-03

WASHINGTON, D.C., December 3, 2014--A new report from the American Institute of Physics (AIP) Statistical Research Center has found that the number of Hispanic students receiving bachelor's degrees in the physical sciences and engineering has increased over the last decade or so, passing 10,000 degrees per year for the first time in 2012. The overall number of U.S. students receiving degrees in those fields also increased over the same time, but it increased faster among Hispanics.

From 2002 to 2012, the number of Hispanics earning bachelor's degrees in the physical sciences ...

New path of genetic research: Scientists uncover 4-stranded elements of maize DNA

2014-12-03

TALLAHASSEE, Fla. -- A team led by Florida State University researchers has identified DNA elements in maize that could affect the expression of hundreds or thousands of genes.

"Maybe they are part of the machinery that allows an organism to turn hundreds of genes off or on," said Associate Professor of Biological Science Hank Bass.

Bass and Carson Andorf, a doctoral student in computer science at Iowa State University, began this exploration of the maize genome sequence along with colleagues from FSU, Iowa State and the University of Florida. They wanted to know ...

Chemotherapy can complicate immediate breast reconstruction after mastectomy

2014-12-03

New York, NY, December 2, 2014 - Immediate breast reconstruction following mastectomy is becoming more prevalent. However, in breast cancer patients undergoing simultaneous chemotherapy, thrombotic complications can arise that can delay or significantly modify reconstructive plans. Outcomes of cases illustrating potential complications are published in the current issue of Annals of Medicine and Surgery.

Chemotherapy is increasingly used to treat larger operable or advanced breast cancer prior to surgery. Chemotherapy delivered via the placement of a central venous line ...

Not all induced pluripotent stem cells are made equal: McMaster researchers

2014-12-03

Hamilton, ON (Dec. 3, 2014) - Scientists at McMaster University have discovered that human stem cells made from adult donor cells "remember" where they came from and that's what they prefer to become again.

This means the type of cell obtained from an individual patient to make pluripotent stem cells, determines what can be best done with them. For example, to repair the lung of a patient with lung disease, it is best to start off with a lung cell to make the therapeutic stem cells to treat the disease, or a breast cell for the regeneration of tissue for breast cancer ...

Computer model enables design of complex DNA shapes

2014-12-03

CAMBRIDGE, MA -- MIT biological engineers have created a new computer model that allows them to design the most complex three-dimensional DNA shapes ever produced, including rings, bowls, and geometric structures such as icosahedrons that resemble viral particles.

This design program could allow researchers to build DNA scaffolds to anchor arrays of proteins and light-sensitive molecules called chromophores that mimic the photosynthetic proteins found in plant cells, or to create new delivery vehicles for drugs or RNA therapies, says Mark Bathe, an associate professor ...

Mediterranean diet linked to improved CV function in erectile dysfunction patients

2014-12-03

Vienna, Austria - 3 December 2014: The Mediterranean diet is linked to improved cardiovascular performance in patients with erectile dysfunction, according to research presented at EuroEcho-Imaging 2014 by Dr Athanasios Angelis from Greece. Patients with erectile dysfunction who had poor adherence to the Mediterranean diet had more vascular and cardiac damage.

EuroEcho-Imaging is the annual meeting of the European Association of Cardiovascular Imaging (EACVI), a branch of the European Society of Cardiology (ESC), and is held 3-6 December in Vienna, Austria.

Dr Angelis ...

Interventional radiology procedure preserves uterus in patients with placenta accreta

2014-12-03

CHICAGO - Researchers reported today on a procedure that can preserve fertility and potentially save the lives of women with a serious pregnancy complication called placenta accreta. Results of the new study presented at the annual meeting of the Radiological Society of North America (RSNA) showed that placement of balloons in the main artery of the mother's pelvis prior to a Caesarean section protects against hemorrhage and is safe for both mother and baby.

Placenta accreta, a condition in which the placenta abnormally implants in the uterus, can lead to additional complications, ...

Many chest X-rays in children are unnecessary

2014-12-03

CHICAGO - Researchers at Mayo Clinic found that some children are receiving chest X-rays that may be unnecessary and offer no clinical benefit to the patient, according to a study presented today at the annual meeting of the Radiological Society of North America (RSNA).

"Chest X-rays can be a valuable exam when ordered for the correct indications," said Ann Packard, M.D., radiologist at the Mayo Clinic in Rochester, Minn. "However, there are several indications where pediatric chest X-rays offer no benefit and likely should not be performed to decrease radiation dose ...

LAST 30 PRESS RELEASES:

Nurses can deliver hospital care just as well as doctors

From surface to depth: 3D imaging traces vascular amyloid spread in the human brain

Breathing tube insertion before hospital admission for major trauma saves lives

Unseen planet or brown dwarf may have hidden 'rare' fading star

Study: Discontinuing antidepressants in pregnancy nearly doubles risk of mental health emergencies

Bipartisan members of congress relaunch Congressional Peripheral Artery Disease (PAD) Caucus with event that brings together lawmakers, medical experts, and patient advocates to address critical gap i

Antibody-drug conjugate achieves high response rates as frontline treatment in aggressive, rare blood cancer

Retina-inspired cascaded van der Waals heterostructures for photoelectric-ion neuromorphic computing

Seashells and coconut char: A coastal recipe for super-compost

Feeding biochar to cattle may help lock carbon in soil and cut agricultural emissions

Researchers identify best strategies to cut air pollution and improve fertilizer quality during composting

International research team solves mystery behind rare clotting after adenoviral vaccines or natural adenovirus infection

The most common causes of maternal death may surprise you

A new roadmap spotlights aging as key to advancing research in Parkinson’s disease

Research alert: Airborne toxins trigger a unique form of chronic sinus disease in veterans

University of Houston professor elected to National Academy of Engineering

UVM develops new framework to transform national flood prediction

Study pairs key air pollutants with home addresses to track progression of lost mobility through disability

Keeping your mind active throughout life associated with lower Alzheimer’s risk

TBI of any severity associated with greater chance of work disability

Seabird poop could have been used to fertilize Peru's Chincha Valley by at least 1250 CE, potentially facilitating the expansion of its pre-Inca society

Resilience profiles during adversity predict psychological outcomes

AI and brain control: A new system identifies animal behavior and instantly shuts down the neurons responsible

Suicide hotline calls increase with rising nighttime temperatures

What honey bee brain chemistry tells us about human learning

Common anti-seizure drug prevents Alzheimer’s plaques from forming

Twilight fish study reveals unique hybrid eye cells

Could light-powered computers reduce AI’s energy use?

Rebuilding trust in global climate mitigation scenarios

Skeleton ‘gatekeeper’ lining brain cells could guard against Alzheimer’s

[Press-News.org] People conceived during the Dutch famine have altered regulation of growth genesMay have helped these individuals to adjust to conditions