High-sugar diet in fathers can lead to obese offspring

2014-12-04

(Press-News.org) A new study shows that increasing sugar in the diet of male fruit flies for just 1 or 2 days before mating can cause obesity in their offspring through alterations that affect gene expression in the embryo. There is also evidence that a similar system regulates obesity susceptibility in mice and humans. The research, which is published online December 4 in the Cell Press journal Cell, provides insights into how certain metabolic traits are inherited and may help investigators determine whether they can be altered.

Research has shown that various factors that are passed on by parents or are present in the uterine environment can affect offspring's metabolism and body type. Investigators led by Dr. J. Andrew Pospisilik, of the Max Planck Institute of Immunobiology and Epigenetics in Germany, and team member Dr. Anita Öst, now at Linkoping University in Sweden, sought to understand whether normal fluctuations in a parent's diet might have such an impact on the next generation.

Through mating experiments in Drosophila melanogaster, or fruit flies, the scientists found that dietary interventions in males could change the body composition of offspring, with increased sugar leading to obesity in the next generation. High dietary sugar increased gene expression through epigenetic changes, which affect gene activity without changing the DNA's underlying sequence. "To use computer terms, if our genes are the hardware, our epigenetics is the software that decides how the hardware is used," explains Dr. Öst. "It turns out that the father's diet reprograms the epigenetic 'software' so that genes needed for fat production are turned on in their sons."

Because epigenetic programs are somewhat plastic, the investigators suspect that it might be possible to reprogram obese epigenetic programs to lean epigenetic programs. "At the moment, we and other researchers are manipulating the epigenetics in early life, but we don't know if it is possible to rewrite an adult program," says Dr. Öst.

The fruit fly models and experiments that the team designed will be valuable resources for the scientific community. Because the flies reproduce quickly, they can allow investigators to quickly map out the details of how nutrition and other environmental stimuli affect epigenetics and whether or not they can be modulated, both early and later in life.

"It's very early days for our understanding of how parental experiences can stably reprogram offspring physiology, lifelong. The mechanisms mapped here, which seem in some way to be conserved in mouse and man, provide a seed for research that has the potential to profoundly change views and practices in medicine," says Dr. Pospisilik.

INFORMATION:

Cell, Öst et al.: "Paternal diet defines offspring chromatin state and intergenerational obesity"

ELSE PRESS RELEASES FROM THIS DATE:

2014-12-04

New Caledonian crows--well known for their impressive stick-wielding abilities--show preferences when it comes to holding their tools on the left or the right sides of their beaks, in much the same way that people are left- or right-handed. Now researchers reporting in the Cell Press journal Current Biology on December 4 suggest that those bill preferences allow each bird to keep the tip of its tool in view of the eye on the opposite side of its head. Crows aren't so much left- or right-beaked as they are left- or right-eyed.

"If you were holding a brush in your mouth ...

2014-12-04

Blood cancers are more common in men than in women, but it has not been clear why this is the case. A study published by Cell Press December 4th in Cell Stem Cell provides an explanation, revealing that female sex hormones called estrogens regulate the survival, proliferation, and self-renewal of stem cells that give rise to blood cancers. Moreover, findings in mice with blood neoplasms--the excessive production of certain blood cells--suggest that a drug called tamoxifen, which targets estrogen receptors and is approved for the treatment of breast cancer, may also be a ...

2014-12-04

In a breakthrough study to be published on the December 4th issue of the prestigious scientific journal Cell, a research team led by Miguel Soares at the Instituto Gulbenkian de Ciência (IGC; Portugal) discovered that specific bacterial components in the human gut microbiota can trigger a natural defense mechanism that is highly protective against malaria transmission.

Over the past few years, the scientific community became aware that humans live under a continuous symbiotic relationship with a vast community of bacteria and other microbes that reside in the gut. ...

2014-12-04

This discovery has a potential application in the treatment of certain blood disorders for which there is currently no cure. The study was led by Dr. Simón Méndez-Ferrer of the CNIC, working in partnership with the laboratories of Doctors Jürg Schwaller and Radek Skoda of the University Hospital in Basel (Switzerland). The study's authors have demonstrated in mice that tamoxifen, a drug already approved and widely used for the treatment of breast cancer, blocks the symptoms and the progression of a specific group of blood disorders known as myeloproliferative ...

2014-12-04

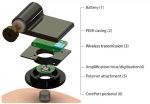

PROVIDENCE, R.I. [Brown University] -- In a study in the journal Neuron, scientists describe a new high data-rate, low-power wireless brain sensor. The technology is designed to enable neuroscience research that cannot be accomplished with current sensors that tether subjects with cabled connections.

Experiments in the paper confirm that new capability. The results show that the technology transmitted rich, neuroscientifically meaningful signals from animal models as they slept and woke or exercised.

"We view this as a platform device for tapping into the richness of ...

2014-12-04

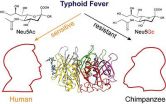

The bacterium Salmonella Typhi causes typhoid fever in humans, but leaves other mammals unaffected. Researchers at University of California, San Diego and Yale University Schools of Medicine now offer one explanation -- CMAH, an enzyme that humans lack. Without this enzyme, a toxin deployed by the bacteria is much better able to bind and enter human cells, making us sick. The study is published in the Dec. 4 issue of Cell.

In most mammals (including our closest evolutionary cousins, the great apes), the CMAH enzyme reconfigures the sugar molecules found on these animals' ...

2014-12-04

The link between obesity and cardiovascular diseases is well acknowledged. Being obese or overweight is a major risk factor for the development of elevated blood pressure, and cardiovascular diseases. But it has net been known how obesity increases the risk of high blood pressure, making it difficult to develop evidence based therapies for obesity, hypertension and heart disease.

In a ground-breaking study, published today in the prestigious journal, Cell (embargo midday EST), researchers from Monash University in Australia, Warwick, Cambridge in the UK and several American ...

2014-12-04

Leptin, a hormone that regulates the amount of fat stored in the body, also drives the increase in blood pressure that occurs with weight gain, according to researchers from Monash University and the University of Cambridge.

Being obese or overweight is a major risk factor for the development of high blood pressure and cardiovascular disease. Whilst a number of factors may be involved, the precise explanation for the link between these two conditions has been unclear.

In a study published today in the journal Cell, a research team led by Professor Michael Cowley, ...

2014-12-04

PHILADELPHIA--People with mental illness are more likely to have been tested for HIV than those without mental illness, according to a new study from a team of researchers at Penn Medicine and the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) published online this week in AIDS Patient Care and STDs. The researchers also found that the most seriously ill - those with schizophrenia and bipolar disease - had the highest rate of HIV testing.

The study assessed nationally representative data from 21,785 adult respondents from the 2007 National Health Interview Survey ...

2014-12-04

EAST LANSING, Mich. - Take two poisonous mushrooms, and call me in the morning. While no doctor would ever write this prescription, toxic fungi may hold the secrets to tackling deadly diseases.

A team of Michigan State University scientists has discovered an enzyme that is the key to the lethal potency of poisonous mushrooms. The results, published in the current issue of the journal Chemistry and Biology, reveal the enzyme's ability to create the mushroom's molecules that harbor missile-like proficiency in attacking and annihilating a single vulnerable target in the ...

LAST 30 PRESS RELEASES:

[Press-News.org] High-sugar diet in fathers can lead to obese offspring