(Press-News.org) LOS ANGELES - (Dec. 8, 2014) - In the U.S. and around the globe, skin and soft tissue infections caused by methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA) continue to endanger the health and lives of patients and otherwise healthy individuals.

Treatment is difficult because MRSA is resistant to many antibiotics, and the infections can recur, placing family members and other close contacts at risk of infection.

A study reported online today in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences USA holds new hope for preventing or reducing the severity of infections caused by the "superbug" MRSA. In the study, infectious disease specialists at the Los Angeles Biomedical Research Institute at Harbor-UCLA Medical Center (LA BioMed) reported that a new investigational vaccine, NDV-3, employing the recombinant protein Als3, can mobilize the immune system to fight off MRSA skin infections in an experimental model. The researchers found the vaccine works by enhancing molecular and cellular immune defenses of the skin in response to MRSA and other S. aureus bacteria in disease models.

"This is the first published study to demonstrate the effectiveness of a cross-kingdom recombinant vaccine against MRSA skin infections," said Dr. Michael R. Yeaman, lead author of the study. "NDV-3 is unique as it is the first vaccine to demonstrate it can be effective in protecting against infections caused by both S. aureus and the fungus Candida albicans. NDV-3 represents a novel approach to vaccine design."

The research team found the NDV-3 vaccine reduced severity and progression of skin infection in a model of the MRSA-caused disease, and prevented MRSA invasion from the skin to deeper tissues. The team said these findings support further evaluation of NDV-3 to address disease caused by S. aureus in humans. NDV-3 has been licensed to NovaDigm Therapeutics, Inc. and has already been found to be well-tolerated and capable of producing immune responses in human clinical trials similar to those observed to be effective in the present disease model.

A vaccine to prevent or minimize infections caused by S. aureus could significantly improve public health because this pathogen is the leading cause of skin and skin structure infections, which can lead to life-threatening blood infections. It is also a significant cause of surgical or traumatic wound infections, diabetic skin lesions, bloodstream infections and pneumonia or endocarditis.

"Up to one-third of patients diagnosed with invasive S. aureus infections die, accounting for more annual deaths than HIV, tuberculosis and viral hepatitis combined," Dr. Yeaman said. "A vaccine that could prevent or lessen the severity of MRSA infections would be a significant advance in patient care and public health."

INFORMATION:

The study was funded, in part, by National Institutes of Health grants AI-111661 and AI-063382; U.S. Department of Defense grant W81XWH-10-2-0035, and NovaDigm Therapeutics, Inc. In addition to his work at LA BioMed, Dr. Yeaman is professor of medicine at the David Geffen School of Medicine at UCLA, and chief, Division of Molecular Medicine, Harbor-UCLA Medical Center. Key research team members who also contributed to the study were: Scott G. Filler, Siyang Chaili, Kevin Barr, Huiyuan Wang, Deborah Kupferwasser, John P. Hennessey Jr., Yue Fu, Clint S. Schmidt, John E. Edwards Jr., Yan Q. Xiong and Ashraf S. Ibrahim.

About LA BioMed

Founded in 1952, LA BioMed is one of the country's leading nonprofit independent biomedical research institutes. It has approximately 100 principal researchers conducting studies into improved diagnostics and treatments for cancer, inherited diseases, infectious diseases, illnesses caused by environmental factors and more. It also educates young scientists and provides community services, including prenatal counseling and childhood nutrition programs. LA BioMed is academically affiliated with the David Geffen School of Medicine at UCLA and located on the campus of Harbor-UCLA Medical Center. For more information, please visit http://www.LABioMed.org

About NovaDigm

NovaDigm is developing innovative vaccines to protect patients from fungal and bacterial infections, which can be recurrent, drug-resistant and in some cases, life-threatening. The Company's founding scientists from LA BioMed are recognized leaders in the field of infectious disease and the emerging threat of "superbugs." Their work has been largely funded by the National Institutes of Health National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases. NovaDigm's lead product candidates target Candida, a fungal pathogen, and Staphylococcus aureus, including MRSA. Based in North Dakota with additional research activities at LA BioMed, NovaDigm has received funding from Domain Associates, a leading U.S. health care venture capital firm and RusnanoMedInvest, a Russian venture capital firm. The company also collaborates with multiple government agencies. For more information, please visit http://www.novadigmtherapeutics.com.

Everyday events are easy to forget, but unpleasant ones can remain engraved in the brain. A new study published in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences identifies a neural mechanism through which unpleasant experiences are translated into signals that trigger fear memories by changing neural connections in a part of the brain called the amygdala. The findings show that a long-standing theory on how the brain forms memories, called Hebbian plasticity, is partially correct, but not as simple as was originally proposed.

The effort led by Joshua Johansen from ...

A new genetic therapy not only helped blind mice regain enough light sensitivity to distinguish flashing from non-flashing lights, but also restored light response to the retinas of dogs, setting the stage for future clinical trials of the therapy in humans.

The therapy employs a virus to insert a gene for a common ion channel into normally blind cells of the retina that survive after the light-responsive rod and cone photoreceptor cells die as a result of diseases such as retinitis pigmentosa. Photoswitches - chemicals that change shape when hit with light -are then ...

CAMBRIDGE, Mass. (December 8, 2014) - Long known for its ability to help organisms successfully adapt to environmentally stressful conditions, the highly conserved molecular chaperone heat-shock protein 90 (HSP90) also enables estrogen receptor-positive (ER+) breast cancers to develop resistance to hormonal therapy.

This HSP90-mediated evolutionary mechanism of drug resistance, reported by Whitehead Institute scientists in this week's online edition of the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences (PNAS), provides a strong therapeutic rationale for combining HSP90 ...

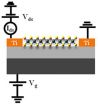

Two-dimensional (2D) layered materials are now attracting a lot of interest due to their unique optoelectronic properties at atomic thicknesses. Among them, graphene has been mostly investigated, but the zero-gap nature of graphene limits its practical applications. Therefore, 2D layered materials with intrinsic band gaps such as MoS2, MoSe2, and MoTe2 are of interest as promising candidates for ultrathin and high-performance optoelectronic devices.

Here, Pil Ju Ko and colleagues at Toyohashi University of Technology, Japan have fabricated back-gated field-effect phototransistors ...

Hummingbirds' remarkable ability to hover in place is highly contingent on the tiny bird having a completely stationary visual field, according to University of British Columbia research published in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences.

UBC zoologists Benjamin Goller and Douglas Altshuler projected moving spiral and striped patterns in front of free-flying hummingbirds attempting to feed from a stationary feeder.

Even minimal background pattern motion caused the hummingbirds to lose positional stability and drift. Giving the birds time to get used ...

A new advance in biomedical research at the University of Leicester could have potential in the future to assist with tackling diseases and conditions associated with ageing - as well as in treating cancer.

The research, which has shown promise in clinical samples, has been published in the prestigious scientific journal, Cell Death and Disease.

The group of scientists coordinated by Dr Salvador Macip from the Mechanisms of Cancer and Ageing Lab and the Department of Biochemistry of the University of Leicester carried out the study to find new ways of identifying old ...

You don't have to be a jerk to come up with fresh and original ideas, but sometimes being disagreeable is just what's needed to sell your brainchild successfully to others. However, difficult or irritating people should be aware of the social context in which they are presenting their ideas. A pushy strategy will not always be equally successful, warn Samuel Hunter of Pennsylvania State University and Lily Cushenbery of Stony Brook University in the US, in an article in Springer's Journal of Business and Psychology.

People are often labelled as jerks if they are disagreeable ...

CAMBRIDGE, MA -- MIT chemists have devised a new way to wirelessly detect hazardous gases and environmental pollutants, using a simple sensor that can be read by a smartphone.

These inexpensive sensors could be widely deployed, making it easier to monitor public spaces or detect food spoilage in warehouses. Using this system, the researchers have demonstrated that they can detect gaseous ammonia, hydrogen peroxide, and cyclohexanone, among other gases.

"The beauty of these sensors is that they are really cheap. You put them up, they sit there, and then you come around ...

Researchers have long wondered if there is an upper limit to our capacity to store memories and how we manage to remember so many events without mixing up events that are very similar.

To explore this issue, researchers at the Norwegian University of Science and Technology's (NTNU) Kavli Institute for Systems Neuroscience and Centre for Neural Computation and colleagues from the Czech Republic and Italy tested the ability of rats to remember a number of distinct but similar locations. Their findings are published in the 8 December edition of the Proceedings of the National ...

Technology that can map out the genes at work in a snake or lizard's mouth has, in many cases, changed the way scientists define an animal as venomous. If oral glands show expression of some of the 20 gene families associated with "venom toxins," that species gets the venomous label.

But, a new study from The University of Texas at Arlington challenges that practice, while also developing a new model for how snake venoms came to be. The work, which is being published in the journal Molecular Biology and Evolution, is based on a painstaking analysis comparing groups of ...