Nanotechnology against malaria parasites

2014-12-09

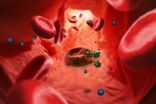

(Press-News.org) Malaria parasites invade human red blood cells; they then disrupt them and infect others. Researchers at the University of Basel and the Swiss Tropical and Public Health Institute (Swiss TPH) have now developed so-called nanomimics of host cell membranes that trick the parasites. This could lead to novel treatment and vaccination strategies in the fight against malaria and other infectious diseases. Their research results have been published in the scientific journal ACS Nano.

For many infectious diseases no vaccine currently exists. In addition, resistance against currently used drugs is spreading rapidly. To fight these diseases, innovative strategies using new mechanisms of action are needed. The malaria parasite Plasmodium falciparum that is transmitted by the Anopheles mosquito is such an example. Malaria is still responsible for more than 600,000 deaths annually, especially affecting children in Africa (WHO, 2012).

Artificial bubbles with receptors

Malaria parasites normally invade human red blood cells in which they hide and reproduce. They then make the host cell burst and infect new cells. Using nanomimics, this cycle can now be effectively disrupted: The egressing parasites now bind to the nanomimics instead of the red blood cells.

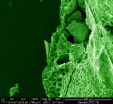

Researchers of groups led by Prof. Wolfgang Meier, Prof. Cornelia Palivan (both at the University of Basel) and Prof. Hans-Peter Beck (Swiss TPH) have successfully designed and tested host cell nanomimics. For this, they developed a simple procedure to produce polymer vesicles - small artificial bubbles - with host cell receptors on the surface. The preparation of such polymer vesicles with water-soluble host receptors was done by using a mixture of two different block copolymers. In aqueous solution, the nanomimics spontaneously form by self-assembly.

Blocking parasites efficiently

Usually, the malaria parasites destroy their host cells after 48 hours and then infect new red blood cells. At this stage, they have to bind specific host cell receptors. Nanomimics are now able to bind the egressing parasites, thus blocking the invasion of new cells. The parasites are no longer able to invade host cells; however, they are fully accessible to the immune system.

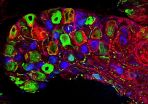

The researchers examined the interaction of nanomimics with malaria parasites in detail by using fluorescence and electron microscopy. A large number of nanomimics were able to bind to the parasites and the reduction of infection through the nanomimics was 100-fold higher when compared to a soluble form of the host cell receptors. In other words: In order to block all parasites, a 100 times higher concentration of soluble host cell receptors is needed, than when the receptors are presented on the surface of nanomimics.

"Our results could lead to new alternative treatment and vaccines strategies in the future", says Adrian Najer first-author of the study. Since many other pathogens use the same host cell receptor for invasion, the nanomimics might also be used against other infectious diseases. The research project was funded by the Swiss National Science Foundation and the NCCR "Molecular Systems Engineering".

INFORMATION:

Original source

Adrian Najer, Dalin Wu, Andrej Bieri, Françoise Brand, Cornelia G. Palivan, Hans-Peter Beck, and Wolfgang Meier

Nanomimics of Host Cell Membranes Block Invasion and Expose Invasive Malaria Parasites

http://pubs.acs.org/doi/abs/10.1021/nn5054206

ACS Nano, Publication Date (Web): 29 November 2014 | DOI: 10.1021/nn5054206

[Attachments] See images for this press release:

ELSE PRESS RELEASES FROM THIS DATE:

2014-12-09

This news release is available in German.

In the course of evolution, animals have become adapted to certain food sources, sometimes even to plants or to fruits that are actually toxic. The driving forces behind such adaptive mechanisms are often unknown. Scientists at the Max Planck Institute for Chemical Ecology in Jena, Germany, have now discovered why the fruit fly Drosophila sechellia is adapted to the toxic fruits of the morinda tree. Drosophila sechellia females, which lay their eggs on these fruits, carry a mutation in a gene that inhibits egg production. ...

2014-12-09

Scientists can now explore nerves in mice in much greater detail than ever before, thanks to an approach developed by scientists at the European Molecular Biology Laboratory (EMBL) in Monterotondo, Italy. The work, published online today in Nature Methods, enables researchers to easily use artificial tags, broadening the range of what they can study and vastly increasing image resolution.

"Already we've been able to see things that we couldn't see before," says Paul Heppenstall from EMBL, who led the research. "Structures such as nerves arranged around a hair on the skin; ...

2014-12-09

Researchers found out that the conformational defect in a specific protein causes Autosomal Dominant Lateral Temporal Lobe Epilepsy (ADLTE) which is a form of familial epilepsy. They showed that treatment with chemical corrector called "chemical chaperone" ameliorates increased seizure susceptibility in a mouse model of human epilepsy by correcting the conformational defect. This was published in Nature Medicine (December 8, 2014 electronic edition).

Mutations in the gene LGI1, encoding a secreted protein, cause familial temporal lobe epilepsy. The research group of ...

2014-12-09

ALBUQUERQUE, N.M. -- Changing flesh to stone sounds like the work of a witch in a fairy tale.

But a new technique to transmute living cells into more permanent materials that defy rot and can endure high-powered probes is widening research opportunities for biologists who are developing cancer treatments, tracking stem cell evolution or even trying to understand how spiders vary the quality of the silk they spin.

The simple, silica-based method also offers materials scientists the ability to "fix" small biological entities like red blood cells into more commercially ...

2014-12-09

As sand dunes march across the Sahara, vast dunes cross the surface of Saturn's largest moon, Titan. New research from a refurbished NASA wind tunnel reveals the physics of how particles move in Titan's methane-laden winds and could help to explain why Titan's dunes form in the way they do. The work is published online Dec. 8 in the journal Nature.

"Conditions on Earth seem natural to us, but models from Earth won't work elsewhere," said Bruce White, professor of mechanical and aerospace engineering at the University of California, Davis, and a co-author on the study. ...

2014-12-09

ATLANTA - December 9, 2014- A new American Cancer Society study finds that despite significant drops in smoking rates, cigarettes continue to cause about three in ten cancer deaths in the United States. The study, appearing in the Annals of Epidemiology, concludes that efforts to reduce smoking prevalence as rapidly as possible should be a top priority for the U.S. public health efforts to prevent cancer deaths.

More than 30 years ago, a groundbreaking analysis by famed British researchers, Richard Doll and Richard Peto, calculated that 30 percent of all cancer deaths ...

2014-12-09

Whether we're paying attention to something we see can be discerned by monitoring the firings of specific groups of brain cells. Now, new work from Johns Hopkins shows that the same holds true for the sense of touch. The study brings researchers closer to understanding how animals' thoughts and feelings affect their perception of external stimuli.

The results were published Nov. 25 in the journal PLoS Biology.

"There is so much information available in the world that we cannot process it all," says Ernst Niebur, Ph.D., a professor of neuroscience in the Johns Hopkins ...

2014-12-09

LIVERMORE, Calif. -- Large-scale storage of low-pressure, gaseous hydrogen in salt caverns and other underground sites for transportation fuel and grid-scale energy applications offers several advantages over above-ground storage, says a recent Sandia National Laboratories study sponsored by the Department of Energy's Fuel Cell Technologies Office.

Geologic storage of hydrogen gas could make it possible to produce and distribute large quantities of hydrogen fuel for the growing fuel cell electric vehicle market, the researchers concluded.

Geologic storage solutions ...

2014-12-09

Neuro-rehabilitation (physical therapy, occupational therapy, etc.) helps hemaparetic stroke patients confronted with loss of motor skills on one side of their body, to recover some of their motor functions after a cerebrovascular accident. One of the most promising tracks in neuro-rehabilitation consists in amplifying the motor learning ability after a stroke, in other words how to learn (again) how to make movements with the parts of the human body impacted after a stroke.

Pilot studies have shown at this matter that tDCS (transcranial direct current stimulation) - ...

2014-12-09

Nidelric pugio fossil dates to half a billion years ago and teaches us about the diversity of life in Earth's ancient seas

In life the animal was a 'balloon' shape and was covered in spines, but the squashed fossil resembles a bird's nest

Named in honour of Professor Richard Aldridge from the University of Leicester

A rare 520 million year old fossil shaped like a 'squashed bird's nest' that will help to shed new light on life within Earth's ancient seas has been discovered in China by an international research team - and will honour the memory of a University of ...

LAST 30 PRESS RELEASES:

[Press-News.org] Nanotechnology against malaria parasites