INFORMATION:

The research was funded by the National Science Foundation and the U.S. Department of Energy. The other co-author is Robert Harris at Oregon State University.

For more information, contact Solomon at 206-221-6745 or esolomn@uw.edu and Hautala at 206-543-0596 or hautala@uw.edu.

Warmer Pacific Ocean could release millions of tons of seafloor methane

2014-12-09

(Press-News.org) Off the West Coast of the United States, methane gas is trapped in frozen layers below the seafloor. New research from the University of Washington shows that water at intermediate depths is warming enough to cause these carbon deposits to melt, releasing methane into the sediments and surrounding water.

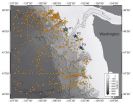

Researchers found that water off the coast of Washington is gradually warming at a depth of 500 meters, about a third of a mile down. That is the same depth where methane transforms from a solid to a gas. The research suggests that ocean warming could be triggering the release of a powerful greenhouse gas.

"We calculate that methane equivalent in volume to the Deepwater Horizon oil spill is released every year off the Washington coast," said Evan Solomon, a UW assistant professor of oceanography. He is co-author of a paper to appear in Geophysical Research Letters.

While scientists believe that global warming will release methane from gas hydrates worldwide, most of the current focus has been on deposits in the Arctic. This paper estimates that from 1970 to 2013, some 4 million metric tons of methane has been released from hydrate decomposition off Washington. That's an amount each year equal to the methane from natural gas released in the 2010 Deepwater Horizon blowout off the coast of Louisiana, and 500 times the rate at which methane is naturally released from the seafloor.

"Methane hydrates are a very large and fragile reservoir of carbon that can be released if temperatures change," Solomon said. "I was skeptical at first, but when we looked at the amounts, it's significant."

Methane is the main component of natural gas. At cold temperatures and high ocean pressure, it combines with water into a crystal called methane hydrate. The Pacific Northwest has unusually large deposits of methane hydrates because of its biologically productive waters and strong geologic activity. But coastlines around the world hold deposits that could be similarly vulnerable to warming.

"This is one of the first studies to look at the lower-latitude margin," Solomon said. "We're showing that intermediate-depth warming could be enhancing methane release."

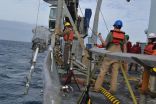

Co-author Una Miller, a UW oceanography undergraduate, first collected thousands of historic temperature measurements in a region off the Washington coast as part of a separate research project in the lab of co-author Paul Johnson, a UW professor of oceanography. The data revealed the unexpected sub-surface ocean warming signal.

"Even though the data was raw and pretty messy, we could see a trend," Miller said. "It just popped out."

The four decades of data show deeper water has, perhaps surprisingly, been warming the most due to climate change.

"A lot of the earlier studies focused on the surface because most of the data is there," said co-author Susan Hautala, a UW associate professor of oceanography. "This depth turns out to be a sweet spot for detecting this trend." The reason, she added, is that it lies below water nearer the surface that is influenced by long-term atmospheric cycles.

The warming water probably comes from the Sea of Okhotsk, between Russia and Japan, where surface water becomes very dense and then spreads east across the Pacific. The Sea of Okhotsk is known to have warmed over the past 50 years, and other studies have shown that the water takes a decade or two to cross the Pacific and reach the Washington coast.

"We began the collaboration when we realized this is also the most sensitive depth for methane hydrate deposits," Hautala said. She believes the same ocean currents could be warming intermediate-depth waters from Northern California to Alaska, where frozen methane deposits are also known to exist.

Warming water causes the frozen edge of methane hydrate to move into deeper water. On land, as the air temperature warms on a frozen hillside, the snowline moves uphill. In a warming ocean, the boundary between frozen and gaseous methane would move deeper and farther offshore. Calculations in the paper show that since 1970 the Washington boundary has moved about 1 kilometer - a little more than a half-mile - farther offshore. By 2100, the boundary for solid methane would move another 1 to 3 kilometers out to sea.

Estimates for the future amount of gas released from hydrate dissociation this century are as high as 0.4 million metric tons per year off the Washington coast, or about quadruple the amount of methane from the Deepwater Horizon blowout each year.

Still unknown is where any released methane gas would end up. It could be consumed by bacteria in the seafloor sediment or in the water, where it could cause seawater in that area to become more acidic and oxygen-deprived. Some methane might also rise to the surface, where it would release into the atmosphere as a greenhouse gas, compounding the effects of climate change.

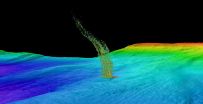

Researchers now hope to verify the calculations with new measurements. For the past few years, curious fishermen have sent UW oceanographers sonar images showing mysterious columns of bubbles. Solomon and Johnson just returned from a cruise to check out some of those sites at depths where Solomon believes they could be caused by warming water.

"Those images the fishermen sent were 100 percent accurate," Johnson said. "Without them we would have been shooting in the dark."

Johnson and Solomon are analyzing data from that cruise to pinpoint what's triggering this seepage, and the fate of any released methane. The recent sightings of methane bubbles rising to the sea surface, the authors note, suggests that at least some of the seafloor gas may reach the surface and vent to the atmosphere.

ELSE PRESS RELEASES FROM THIS DATE:

Long-term endurance training impacts muscle epigenetics

2014-12-09

A new study from Karolinska Institutet in Sweden shows that long-term endurance training in a stable way alters the epigenetic pattern in the human skeletal muscle. The research team behind the study, which is being published in the journal Epigenetics, also found strong links between these altered epigenetic patterns and the activity in genes controlling improved metabolism and inflammation. The results may have future implications for prevention and treatment of heart disease, diabetes and obesity.

"It is well-established that being inactive is perilous, and that regular ...

Nanotechnology against malaria parasites

2014-12-09

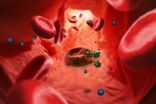

Malaria parasites invade human red blood cells; they then disrupt them and infect others. Researchers at the University of Basel and the Swiss Tropical and Public Health Institute (Swiss TPH) have now developed so-called nanomimics of host cell membranes that trick the parasites. This could lead to novel treatment and vaccination strategies in the fight against malaria and other infectious diseases. Their research results have been published in the scientific journal ACS Nano.

For many infectious diseases no vaccine currently exists. In addition, resistance against ...

Toxic fruits hold the key to reproductive success

2014-12-09

This news release is available in German.

In the course of evolution, animals have become adapted to certain food sources, sometimes even to plants or to fruits that are actually toxic. The driving forces behind such adaptive mechanisms are often unknown. Scientists at the Max Planck Institute for Chemical Ecology in Jena, Germany, have now discovered why the fruit fly Drosophila sechellia is adapted to the toxic fruits of the morinda tree. Drosophila sechellia females, which lay their eggs on these fruits, carry a mutation in a gene that inhibits egg production. ...

Stain every nerve

2014-12-09

Scientists can now explore nerves in mice in much greater detail than ever before, thanks to an approach developed by scientists at the European Molecular Biology Laboratory (EMBL) in Monterotondo, Italy. The work, published online today in Nature Methods, enables researchers to easily use artificial tags, broadening the range of what they can study and vastly increasing image resolution.

"Already we've been able to see things that we couldn't see before," says Paul Heppenstall from EMBL, who led the research. "Structures such as nerves arranged around a hair on the skin; ...

New treatment strategy for epilepsy

2014-12-09

Researchers found out that the conformational defect in a specific protein causes Autosomal Dominant Lateral Temporal Lobe Epilepsy (ADLTE) which is a form of familial epilepsy. They showed that treatment with chemical corrector called "chemical chaperone" ameliorates increased seizure susceptibility in a mouse model of human epilepsy by correcting the conformational defect. This was published in Nature Medicine (December 8, 2014 electronic edition).

Mutations in the gene LGI1, encoding a secreted protein, cause familial temporal lobe epilepsy. The research group of ...

Turning biological cells to stone improves cancer and stem cell research

2014-12-09

ALBUQUERQUE, N.M. -- Changing flesh to stone sounds like the work of a witch in a fairy tale.

But a new technique to transmute living cells into more permanent materials that defy rot and can endure high-powered probes is widening research opportunities for biologists who are developing cancer treatments, tracking stem cell evolution or even trying to understand how spiders vary the quality of the silk they spin.

The simple, silica-based method also offers materials scientists the ability to "fix" small biological entities like red blood cells into more commercially ...

The winds of Titan

2014-12-09

As sand dunes march across the Sahara, vast dunes cross the surface of Saturn's largest moon, Titan. New research from a refurbished NASA wind tunnel reveals the physics of how particles move in Titan's methane-laden winds and could help to explain why Titan's dunes form in the way they do. The work is published online Dec. 8 in the journal Nature.

"Conditions on Earth seem natural to us, but models from Earth won't work elsewhere," said Bruce White, professor of mechanical and aerospace engineering at the University of California, Davis, and a co-author on the study. ...

Smoking still causes large proportion of cancer deaths in the United States

2014-12-09

ATLANTA - December 9, 2014- A new American Cancer Society study finds that despite significant drops in smoking rates, cigarettes continue to cause about three in ten cancer deaths in the United States. The study, appearing in the Annals of Epidemiology, concludes that efforts to reduce smoking prevalence as rapidly as possible should be a top priority for the U.S. public health efforts to prevent cancer deaths.

More than 30 years ago, a groundbreaking analysis by famed British researchers, Richard Doll and Richard Peto, calculated that 30 percent of all cancer deaths ...

Paying attention makes touch-sensing brain cells fire rapidly and in sync

2014-12-09

Whether we're paying attention to something we see can be discerned by monitoring the firings of specific groups of brain cells. Now, new work from Johns Hopkins shows that the same holds true for the sense of touch. The study brings researchers closer to understanding how animals' thoughts and feelings affect their perception of external stimuli.

The results were published Nov. 25 in the journal PLoS Biology.

"There is so much information available in the world that we cannot process it all," says Ernst Niebur, Ph.D., a professor of neuroscience in the Johns Hopkins ...

Storing hydrogen underground could boost transportation, energy security

2014-12-09

LIVERMORE, Calif. -- Large-scale storage of low-pressure, gaseous hydrogen in salt caverns and other underground sites for transportation fuel and grid-scale energy applications offers several advantages over above-ground storage, says a recent Sandia National Laboratories study sponsored by the Department of Energy's Fuel Cell Technologies Office.

Geologic storage of hydrogen gas could make it possible to produce and distribute large quantities of hydrogen fuel for the growing fuel cell electric vehicle market, the researchers concluded.

Geologic storage solutions ...